Remote learning is hard. Especially for children. Even more so for children with a disability.

“It’s too much to ask a child with an ADHD diagnosis to look at a screen for six hours and not get up,” said Dani Wilder, who is set to graduate this month with a degree in biology from Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “These students need stimulation, to move between classes, to talk through questions and collaborate. We knew this before the COVID pandemic, but it’s become all too clear now.”

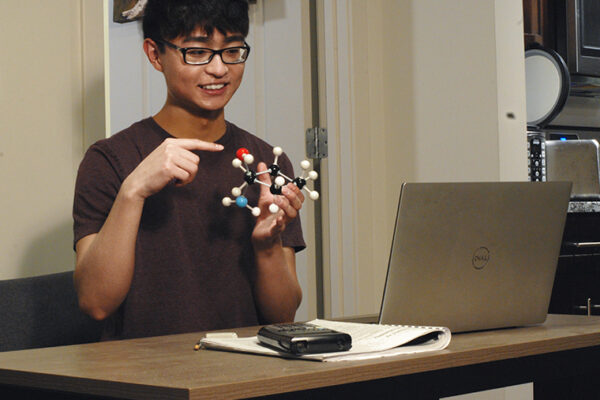

Wilder is helping local students through the WashU Tutoring Initiative, a network of 130 student tutors who lead online lessons in math, science, languages and more for both typical K-12 learners and those with learning or physical disabilities. The program, currently at capacity, supports 440 families in the St. Louis region.

“There weren’t many of us in the beginning, and the need was just so overwhelming and heartbreaking,” Wilder recalled. “I felt like I ran into this starving village with a loaf of bread. But over time, we’ve been able to build this amazing group of students who were looking for ways to help people in our own community.”

Wilder is one of about 1,700 Washington University students who are graduating in December. Because of the pandemic, there is no formal recognition ceremony. December graduates are invited to participate in Commencement next year, on May 21.

Reaching students with disabilities was a priority from the start, Wilder said. Some tutors have a learning disability themselves; some tutors provide services to fellow students through Washington University Disability Resources. And some, like Wilder, fall into both categories.

“We can be more empathetic and more effective because we too are learning to adapt to this new situation,” said Wilder, who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and post-traumatic stress disorder diagnoses. “One of the most valuable lessons WashU has taught me is not to be afraid to ask for help. I hope we’re sharing that lesson with the students we are working with.”

As a new student, Wilder resisted accessing disability resources, fearful that classmates would think less of her. Then she took her first general chemistry quiz.

“I was shaking so badly I could barely put numbers into my calculator,” Wilder recalled. “I walked straight from chemistry to the Disability Resources Center. They not only helped me work out a plan for future chemistry quizzes, but they also offered me a lot of guidance on how to overcome my disabilities in those types of situations.”

Wilder now helps other students, proctoring exams for students with anxiety disorders, escorting students with physical limitations across campus and describing complex graphs for a student who is blind.

“The goal is to make sure the picture I’m describing is the one he sees in his head,” Wilder said. “It takes a lot of time and creativity, and one explanation won’t always get us there. We need to work together as a team.”

Wilder has developed that same relationship with the 9-year-old girl she tutors. The girl, deaf but able to read lips, likes to play online math and spelling games.

“The schools are trying so hard, but it’s been hard to provide the stimulating opportunities students need,” Wilder said. “That’s the fun part for me — getting to know her and watching her learn so fast.”

In the new year, Wilder plans to continue tutoring and will work with her successor to expand the initiative. She also is preparing for a career in medicine. Wilder already has taken the Medical College Admission Test, scoring in the 99th percentile. In addition, she is conducting further market research and product development on a do-it-yourself patch test she designed for people who are allergic or sensitive to makeup. Ultimately, Wilder plans to be a clinical physician, perhaps a dermatologist.

“Medicine and education are alike in a lot of ways,” Wilder said. “Doctors are teachers, too. Every diagnosis has to be translated, and every patient needs to be seen as a whole person.”