President Donald Trump has consistently touted the economy’s pre-COVID-19 success and recent rebound as one of his greatest successes as president, if not one of the greatest economies in U.S. history. But how strong is the economy really? And how much of that success can be attributed to the president? Three experts from the Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis weigh in on Trump’s record, the state of the economy and what to expect from a second Trump term or a Biden administration.

What the president can, and can’t, do to shape the economy

“The president has the ability to stimulate the economy in the short run through tax cuts. That assumes Congress complies with the president’s wishes. Longer term, presidents have much less control over the course of the economy,” said John Horn, professor of practice in economics. “What presidents have the ability to do is to manage the crisis that they are confronted with in order to minimize the impact. But no president can unilaterally create a well-functioning economy.”

Economic success is a lot like winning a football game, according to Glenn MacDonald, the John M. Olin Distinguished Professor of Economics and Strategy.

“Several things have to be done correctly, including offense, defense, play-calling. So no one element suffices to generate success, but failing on one generally means overall failure,” MacDonald said. “Presidential activities are very similar. If they do a good job, and various other things like technology and absence of wars cooperate, then the economy will do well. But, just like bad play-calling can lose a football game, poorly chosen government policies can undo a lot of other good things, and presidents play a key role in those policy choices.”

Tim Solberg, professor of practice in finance, has used Standard and Poor’s market data — going back to the Great Depression — to study market cycles during presidential election years and subsequent years. Interestingly, his research shows Wall Street prefers a split government, meaning that the House, which initiates tax and budget bills, is controlled by the opposite party of the President — providing checks and balances.

“To a large degree, market cycles and economic growth operate on long-term expansion and retractions that override who is in the White House,” Solberg said. “I often tell students that the Federal Reserve Bank controlling the interest rate and the supply of money has more immediate control over the economy than the President or Congress. The Fed didn’t need Congressional approval to increase the money supply by $4 trillion through quantitative easing to provide liquidity in the financial crisis of 2007-09.”

Grading Trump’s economic record

The biggest change by the Trump administration was the lowering of taxes, Solberg said. Because the U.S. corporate tax rate was higher than other countries, U.S. corporations were moving operations overseas to escape taxation.

“The controversial tax reform did lower taxes to meet international competitiveness and enabled corporations to ‘repatriate’ a trillion dollars held overseas from operations of their international divisions. There was a stimulus from that if they invested in capital expenditures such as plant and equipment or research. However, much of it was used to buy back their stock so it aided the stock market rise and benefitted shareholders but did not really affect the overall economy,” Solberg said.

From an economic standpoint, cutting regulations was a boost to the economy, but it came at the cost of reducing environmental protection, Horn said.

On the other hand, the trade war has helped to protect some American jobs, but not a hugely significant number, Horn said. “The economy would have grown faster without the trade wars, but it would have put continued pressure on the jobs of the lower-income workers,” he said.

MacDonald had positive marks for Trump’s first-term economic activity.

“President Trump’s policies have been generally in the direction of lower taxes, more carefully chosen regulations, improving international trade deals, and introducing/enforcing immigration policies, all of which have turned out to be generally good for economic activity,” he said.

How are we doing now?

COVID-19 and the resulting lockdown and ongoing restrictions tossed a massive wrench into the economy. Even today — seven months after the initial lockdown — it is difficult to assess the overall state of the economy. Standard metrics were designed to measure the extent of consumers, employees and businesses voluntarily interacting with one another, MacDonald explained.

“So, normally, high unemployment, for example, really means a decline in economically valuable opportunities for firms and employees to interact. In the present situation, as far as can be determined, there are plenty of opportunities for valuable activities. But the lockdown, then continued partial lockdown, are preventing these from occurring, thereby creating artificially high unemployment numbers. It is very misleading to refer to the current state of economic activity as a ‘recession.’ It is simply a policy-induced reduction in activity,” he said.

Unemployment is improving — down to 7.9% in early October from 14.7% reported in April — but is still above the normal 3-5% that would indicate a strong economy, Solberg said. Recent hiring surges by retailers like Amazon and Walmart have helped, but, on the flip side, there are continued job losses in restaurants, leisure, travel/airlines and small businesses, some of which may never return.

And, there is potential for future losses if there is not another stimulus package, Horn said.

Much attention has been devoted to the stock market, which has outperformed expectations in recent months, but the stock market is not a good indicator of economic stability.

“The stock market is an important indicator of corporate strength as investors invest based on what they think will be future earnings and worth of the companies. But it is one factor,” Solberg said.

Other factors to consider include the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which shrank 7.1% in the second quarter when much of business was in lockdown. The third-quarter rate, which will be announced on Oct. 29, is expected to show a bounce back as businesses have started returning to work, Solberg said. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta is estimating a 7.8% jump for the nation’s economy in the third quarter.

With interest rates low and many people working from home, housing sales have been robust, Solberg said. Yet, as of August, consumer confidence remained low and people were showing caution in spending.

Overall, Solberg said the U.S. economy is surprisingly resilient after the stress of the past two quarters brought on by the COVID-19 shutdown. The economic impact on individual Americans, though, is a different story.

The most unequal recession in modern history

While stock market returns have been high, labor returns have been small. “When unemployment is high, employers don’t need to offer higher wages to attract workers,” Horn said. “The upper end of the income distribution is recovering nicely, while the lower end is staying flat. Estimates show that billionaires alone increased their wealth by over half a trillion dollars during the crisis.”

MacDonald said: “Every change in economic activity impacts different groups of people in different ways. The lockdown and partial reopening have been especially hard on restaurants, bars, hotels, movie theaters, etc., that employ significant numbers of low-wage workers. Thus, in that sense, people in low-wage occupations have been impacted especially hard.”

Looking ahead

Undoubtedly, reviving the struggling economy and decreasing unemployment will be top priorities for the president who emerges from the November election.

“The biggest challenge will be to generate strong, stable growth,” Horn said. “The bounce back in Q3 is partially due to the horrifically low numbers in Q2, not a long-term sustainable rate. Additionally, the president will have to manage relations with China, deal with slowdowns in other major economies, rising health-care costs and health-care insecurity — how the health-care sector is structured — and the aging baby boomer cohort and ramp up in their retirement. Overall, there are a lot of challenges.”

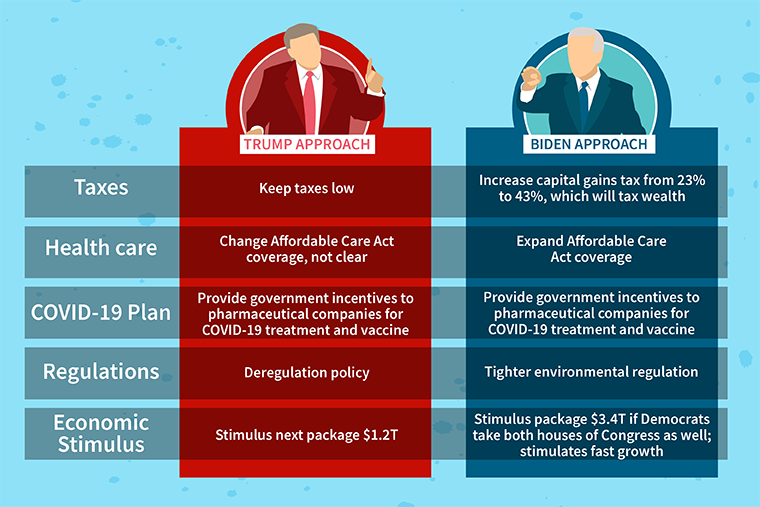

“The next president will have to deal with the significant increase in government expenditures that occurred in 2020 on top of the already serious federal deficit problem,” MacDonald said. “The deficit for 2020 will be around 15% of GDP, the highest since World War II. President Trump would likely deal with this through modest tax increases and more significant spending decreases. Vice President Biden would likely do the opposite.”