“Amnesia is not the right word,” said Geoff K. Ward, “because we’ve forgotten without ever really knowing.”

Ward, professor of African and African American studies in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, was discussing “Truths and Reckonings: The Art of Transformative Racial Justice,” the exhibition he curated for the university’s Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum.

Located in the Kemper Art Museum’s Teaching Gallery, “Truths and Reckonings” confronts histories of racist violence with the aim of untangling their continuing legacies. The exhibition features archival photos, newspaper articles, political cartoons and other materials, as well as contemporary works — by Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Rashid Johnson, Howardena Pindell and Kara Walker, among others — that explore the intersections of art and social justice.

“Americans are so practiced at looking the other way,” Ward said. “Many think, ‘We’ve dealt with this, we’re post-racial, there’s no need to look back.’

“But today that’s no longer plausible,” Ward added. “This exhibit was designed as a counter-memory — and a rebuttal — to such motivated ignorance.”

Seeking understanding

More than a year in the making, “Truths and Reckonings” was organized in conjunction with Ward’s ongoing first-year seminar “Monumental Anti-Racism.” It also builds on Ward’s own investigations into racial violence, social control and white supremacist policing.

“There’s a lot of research going on and lots of evidence about the ways we continue to be impacted by these histories,” said Ward, who also serves as associate director of the university’s new Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity & Equity. (Notably, the center includes an arts and culture initiative.) “That’s why the exhibition exists. But it also happened to coincide with the recent wave of Black Lives Matter protests and with a greater willingness to reflect on these issues.”

“Truths and Reckonings” debuted just a few weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic forced the museum to temporarily close in March of this year. Over the spring and summer, as protests sparked by the death of George Floyd rocked the nation, museum staff built a virtual iteration of the exhibition, and Ward continued hosting personal tours via Zoom.

“That wasn’t the original plan, but COVID has pushed us all to do more with technology,” Ward said. “And, in this case, it helped open the exhibit to a global audience that is suddenly, urgently seeking understanding.”

‘So that liberty might be realized’

Now, with campus partially reopened, “Truths and Reckonings” can again be seen in person by Washington University students, faculty and staff, while the online iteration remains public. However experienced, the exhibition offers a bracing look at the history of slavery, colonialism and genocide — and challenges the idea that their effects “ended long ago.”

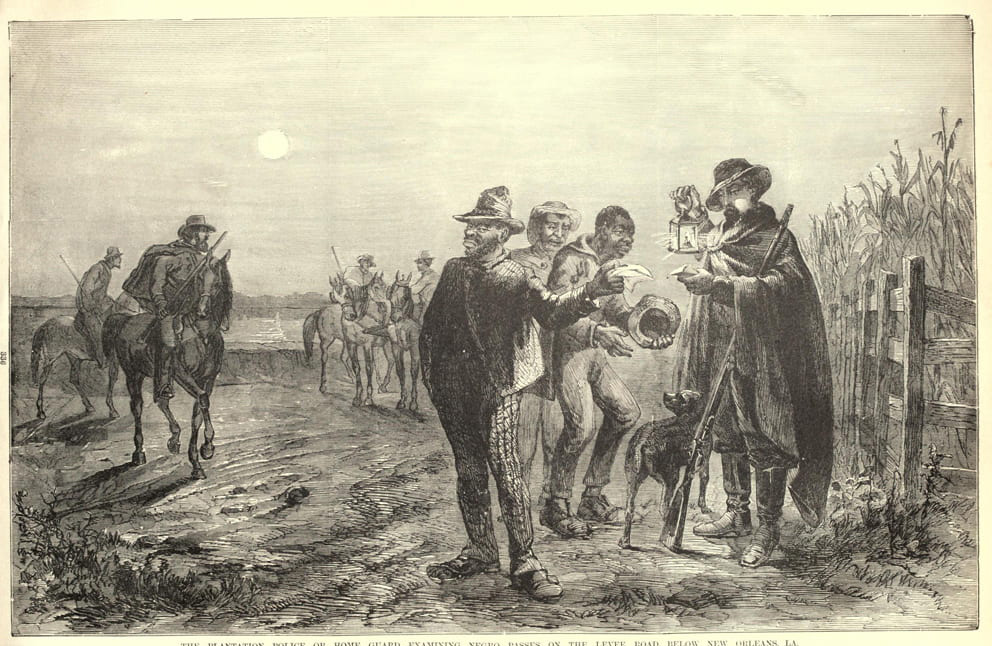

Entering the gallery, one is confronted by Frederick B. Schell’s engraving “Plantation police, or home-guard, examining passes on the road leading to the levee of the Mississippi River” (1863). Schell covered the Civil War for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, drawing battles at Antietam and Vicksburg and traveling with Ulysses S. Grant’s army. This image depicts a Black man impatiently displaying papers to an armed slave patroller. Funded by plantation owners, such patrols were semi-military organizations, drawing members from state militias and Southern military academies. Their ubiquitous surveillance, Ward noted, speaks to a long history of “over-policing and under-protecting.”

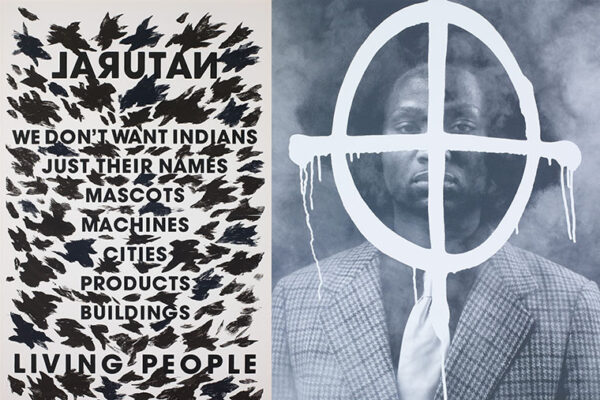

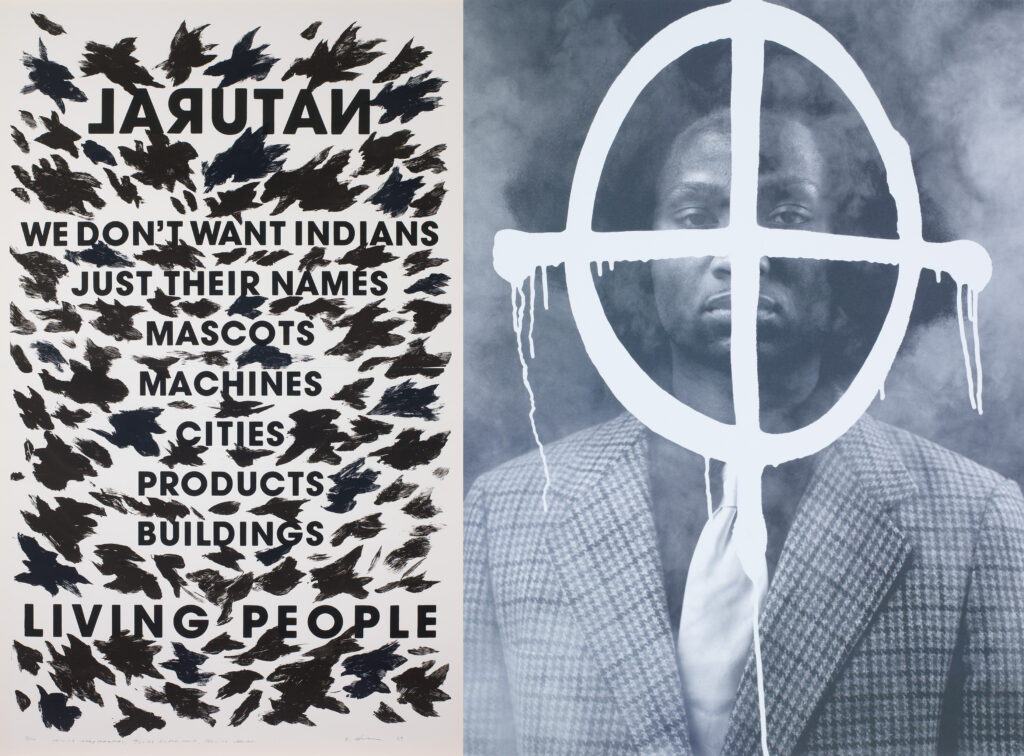

A few steps away in the gallery are six images from Greg Ligon’s “Runaways” (1993). Recalling the format of “Wanted” posters, the series pairs stereotypical illustrations of African Americans with nuanced, sharply rendered textual portraits — a contrast that prefigures a similar flattening in contemporary discourse of “thugs” and “illegals.” Other groupings contrast images of civil rights-era protests with photos from the University Libraries’ “Documenting Ferguson” archive; and colonial-era depictions of Native Americans with Heap of Birds’ monumental print “Telling Many Magpies, Telling Black Wolf, Telling Hachivi” (1989), which calls out appropriation of Native symbols, lands and peoples.

In his curator’s statement, Ward writes that artworks and institutions “inform understanding of the past and our relationship to it.” He describes “Truths and Reckonings” as a “pop-up memorial” that seeks to face history as a step toward change and reconciliation, unsettling “stock notions of American freedom so that liberty might be realized.”

“I do this research as an academic who is interested in these issues who feels that they’re important,” Ward said. “This summer, we’ve seen a kind of great awakening to white supremacy, which can be exhausting, but about which I’m also appreciative.

“I do this work because I want the work available for just these moments.”

“Truths and Reckonings: The Art of Transformative Racial Justice” remains on view through Oct. 14 at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum. Due to COVID-19, the museum is closed to the public but is available by reservation to WashU students, faculty and staff. View the online exhibition here.

Ward will host a virtual tour and Q&A at 5 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 29, as part of the Kemper Art Museum’s “In Conversation” series. Register here. For more information, call 314-935-4523; visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu; or follow the museum on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter or YouTube.