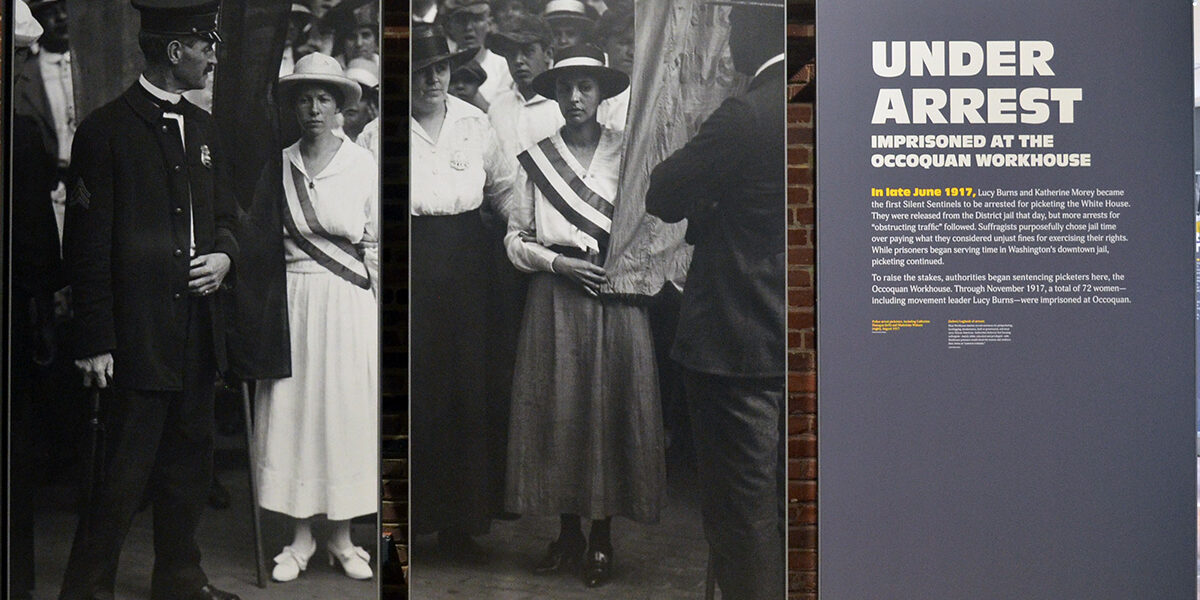

Lucy Burns spent more time in prison than nearly any suffragist in U.S. history. Arrested four times, she served two sentences at the Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton, Virginia, for her activism. At “Lorton,” she endured unsanitary living conditions; spoiled, insect-infested food; and physical and emotional abuse.

She was among the 32 women brutalized there during the aptly-named “Night of Terror,” Nov. 14, 1917. On that night, Burns was beaten, chained to the bars of her jail cell with her hands positioned over her head, and left that way overnight. The next day, she and some of the other suffragists refused to eat and were subsequently force-fed through their noses. Bad press detailing their deplorable treatment at the prison helped shift public sentiment toward the suffragists’ cause, and ultimately pressured President Woodrow Wilson to support women’s enfranchisement.

The women’s suffrage movement lasted nearly a century. Since then, a few women have remained household names, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Ida B. Wells and Alice Paul. Burns’ name, however, is not as well-known today, even though she and Paul co-founded the National Woman’s Party. But thanks to the efforts of Laura Adams McKie, AB ’58, and other dedicated volunteers, that may be changing.

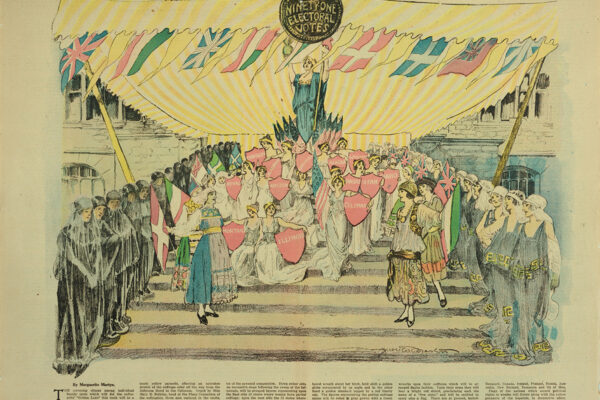

On Jan. 25, 2020, during the 100-year anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, a museum named after Lucy Burns opened on the campus of the Workhouse Arts Center. It is the site of the former Women’s Workhouse (later the D.C. Correctional Facility at Lorton), yet today is a haven for artists. The new museum, which contains original jail cells, details 91 years of prison history (1910–2001) and showcases the suffragists who were imprisoned there.

McKie, who serves as volunteer director, was pivotal to the museum’s realization. A few years after retiring as director of education from the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, McKie ran into a former colleague at a grocery store. The chance encounter led to her receiving an invitation to sit on the board of the Workhouse Arts Center, one of the largest adaptive reuse projects in the country. Having 30 years of experience at the Smithsonian made her an ideal candidate to lead the Workhouse’s efforts to build a museum.

While at the natural history museum, McKie had managed many facilities, including the Discovery Room, the Naturalist Center, the Insect Zoo and the Marine Ecosystem exhibit. She supervised a team of 25 professionals who produced educational materials for families, teachers and students, and developed guides for permanent and temporary exhibits and large format films. She served as the accessibility coordinator for the entire museum and managed the development of fully accessible audio tours. Her department also supervised 300 volunteer docents annually.

Yet moving from directing one department with a defined set of objectives to building an entire museum, especially one with very limited resources, was a major challenge. But it was one McKie welcomed.

“I knew nothing about the evolution of prisons or the whole suffrage story. Of course, I jumped in feet first, as I always do, and swam in all directions.”

Laura McKie

“When I retired, I couldn’t quit learning. It’s not in my nature,” says McKie, who studied cultural anthropology at Washington University and Radcliffe College, receiving a master’s degree from Harvard University.

“I knew nothing about the evolution of prisons or the whole suffrage story,” she says. “Of course, I jumped in feet first, as I always do, and swam in all directions.”

McKie first researched prisons and learned that the Occoquan Workhouse had initially been built as a national model, a 600-acre farm where mainly drunkards and vagrants were sent to work, get fresh air, eat good food, and be rehabilitated. But by the 1960s, the prison complex had become “a horrible place due to drugs and overcrowding. It probably was one of the worst prisons in the country when it closed in 2001,” McKie says.

During the new museum’s development phase, McKie wore many hats, including project manager, curator, writer and collections manager.

“While at the Smithsonian, I would review exhibit scripts for accessibility, but I never had to develop an exhibit myself,” McKie says. “I was never responsible for collections and conservation either.”

For the Lucy Burns Museum, McKie started with just three prison logs. The books had been collected by the late Irma Clifton, a longtime employee of the prison. Minus a few other boxes, most everything else associated with the prison had been thrown away over the years. Remarkably, the arrest books corresponded with the timeframe the suffragists had been imprisoned.

From those books, “I know that 72 women were arrested and sent to the Workhouse prison in 1917,” McKie says. “And I know their names and the amount of time they were sentenced to. And I know what they were arrested for, like ‘obstructing the free passage of the sidewalk’ and ‘obstructing crowds.’ Things that were not crimes.”

The suffragists had taken the bold step of picketing the White House, which was unheard of at the time. Known as the Silent Sentinels, they marched with banners that personally addressed President Wilson and his inaction on women’s enfranchisement. The banners conveyed such sentiments as “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty”; “Mr. President, you say ‘Liberty is the fundamental demand of the human spirit’”; and “Kaiser Wilson, have you forgotten your sympathy with the poor Germans because they were not self-governed? 70,000,000 American women are not self-governed. Take the beam out of your own eye.”

“I mean the gutsiness of picketing, knowing that you were going to be arrested and put into jail. … I think that kind of bravery is something people need to know about.”

Laura McKie

“I mean the gutsiness of picketing, knowing that you were going to be arrested and put into jail. I wouldn’t have had the bravery to do that, especially considering the jail conditions in those days,” McKie says. “I think that kind of bravery is something people need to know about.”

When Lucy Burns and Alice Paul were arrested, police separated them, not wanting the two leaders to be locked up in the same location. Paul was sent to the D.C. jail while Burns went to Lorton. “When we were naming the prison, some considered naming it after Alice Paul because she was more well-known, having authored the Equal Rights Amendment. I said we really couldn’t name it after Paul because she was never held here,” McKie says. “And that’s why we decided to name it after Lucy Burns. Now, I’m hoping somebody someday will write a book about Burns. According to multiple sources, she was always the one out in front of everything.”

Today, McKie has helped return Burns to the front of the suffrage story, and the museum bearing her name will continue to share her story.

In March 2020, McKie received a special proclamation from the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors stating, “We are honoring you for your years of devoted work on the suffrage museum and making the Lucy Burns Museum a reality. We cannot think of a worthier person to honor during the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment.”

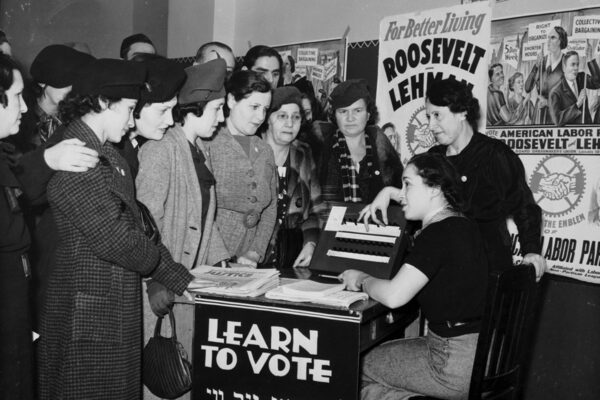

McKie suggests that the best way to honor the women who were willing to fight and die for the right to vote is for all of us today to vote in every election, whether local, state or national.