Kiani Arkus Gardner, AB ’07 (biology), was pretty confident she had the experiment right.

An ambitious Washington University sophomore in the lab of biologist Joseph Jez, she was sure she was asking the right questions, formulating the right hypotheses, following the right procedures.

But the answer wasn’t coming up the way she had hoped.

“We were one or two experiments away from wrapping it up, and having a result to publish,” recalls Gardner, a native Hawaiian and self-professed “science fair nerd,” who matriculated at WashU in the fall of 2003 to study biology and see where the science would take her — academia, research, ultimately perhaps college administration.

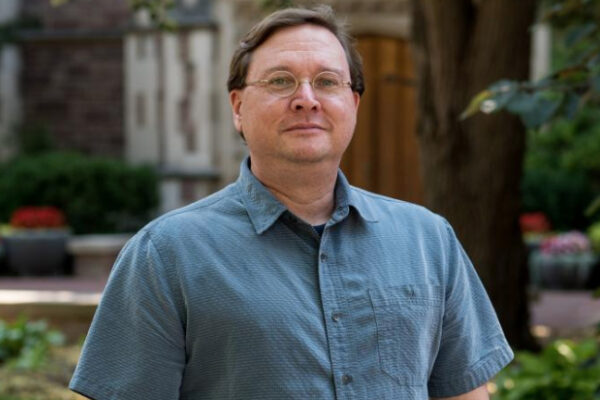

And when the eager first-year student couldn’t find a lab those first two semesters, she landed a summer internship at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center and found herself in the lab of Jez, who is now the Spencer T. Olin Professor in Biology and chair of the Department of Biology in Arts & Sciences. She made an immediate impression, acing every task and earning the right to work alongside Jez and his graduate assistants.

“She was utterly fearless and quite comfortable in the lab,” recalls Jez, who at the time was in his second year as a lab head at the Danforth Center. “We threw everything at her, and she responded beautifully.”

Yet with her goal — publishing her first paper before age 20 — in sight, Gardner became frustrated when those last experiments didn’t turn out the way she had envisioned. “I was pretty upset,” she says, “almost in meltdown mode.” Jez, ever the teacher, patiently listened to the young scientist and told her that the experiments were fine; it was her ideas that were getting in the way.

“He said, ‘Look. The data is what the data is,’” Gardner says. “He told me not to be so in love with your ideas that you’re willing to overlook the data, because that’s where you’re going to go wrong.”

For Gardner, it was a light-bulb moment. “I said, ‘OK, we’ll keep working the experiment, and we’ll get to it,’” she says.

And get to it she did. Gardner studied the data, re-hypothesized and rethought the experiments, and ultimately published that paper, “Mechanistic Analysis of Wheat Chlorophyllase Reveals a Connection to the Carboxyesterase Enzyme Family,” as a sophomore. It was presented at a conference, won an award and appeared in the Notables section of the campus newspaper, The Record, a rare occasion for an undergraduate. And it was the first of a long line of published papers on the vitae for the now 34-year-old Gardner.

Gardner would work three years in Jez’s lab and have eight published papers by the time she graduated in 2007. “I had a bit of street cred,” she says, entering Duke with more publications than most have when they leave the doctorate program.

“I was brash, and I was bold. In fact, my program director told one P.I., ‘If you’re going to take her in the lab, you have to be sure you can handle her,’” she recalls. It made for some tough going early on, but she eventually ended up in the lab of Duke’s Harold Erickson and earned her doctorate in cell biology.

All important lessons for a young scientist: the starts and the stops, two steps forward and one step back, stuck with her as she learned to trust the data at every turn. Jez’s words, “The data is what the data is,” would become her catchphrase.

The words also would be the thread that would take her from WashU to Duke, to marriage and a family, to a career as a community college professor first in North Carolina, to ultimately the southern coast of Alabama in the Mobile metropolitan area.

That’s where this year, Gardner — a Hawaiian, a wife, a mom, a scientist — would throw her hat in the ring as a Democratic candidate for Congress in Alabama’s 1st congressional district, a place that hasn’t sent a Democrat to Congress since 1963. An unlikely candidate in an unprecedented time.

“A force of nature is what she is,” says Jez, who has kept in touch with Gardner through the years as both colleague and friend, and who remembers the day she told him she was a candidate. “She was on the phone from a park, and you could hear her kids playing in the background,” he says. “She’s like, ‘Yeah, I’m running for Congress.’”

No rules

“My life is a series of being in the right place at the right time,” says Gardner via a Zoom call from her kitchen in her Spanish Fort, Ala., home with her two young sons, Ethan, 5, and Nolan, 3, playing nearby.

It’s late June, about 3 weeks before a runoff election in which the voters of south Alabama will choose between two Democratic candidates for the November ballot. It’s been almost four months since the initial primary in early March necessitated a runoff that can finally take place. Why? Because it’s a campaign season cloaked in COVID-19, with social distancing campaigns behind face masks and indoors with YouTube and Facebook Live providing both the messages and the medium.

“It’s good and its bad,” she says, shrugging off the unprecedented challenge. “As far as the pandemic goes, it’s a whole new world, but that’s true for all the candidates. No one has the leg up here. I think I’m a bit more tech savvy, though, and we already had a decent digital infrastructure set up.”

When the campaign began in the summer of 2019, Gardner was a young mom using her PhD to teach biology at a community college, because that’s where she felt she could be the most useful. Even when she was living in North Carolina, she gravitated toward teaching at that level. “I really like the community college, the teaching philosophies and its role in society,” she says.

But when the family moved to rural Alabama for her husband Matt’s job, she found a vastly different world, and she got involved in local politics because she wanted to improve the community in which she and Matt were raising their boys.

“I had already begun to get involved,” she says, “insofar as ‘How do I make sure the community in which I live is one that my children can enter into, and no one has to move across the world to get a good job?’”

“Since I had a following, and a platform and a message, the campaign pivoted from asking for votes to providing leadership.”

Kiani Gardner

When members of the local Democratic party witnessed her intellect and enthusiasm for public service, they came calling for a PhD with no political experience to run for Congress. She first thought it was the craziest thing she had ever heard, but then she finally said yes — with the support of her family. “If you’re going to do it, do it right and do it well,” her husband advised her. “Quit your job and make this what you do.”

In July 2019, she made it official, and Gardner says the campaign was going pretty much as expected, with lots of hand-shaking and church picnics. But then you-know-what happened. The scientist simply took campaign matters in her own hands and pivoted. “There are no rules in place for a pandemic campaign,” she says. “Since I had a following, and a platform and a message, the campaign pivoted from asking for votes to providing leadership.”

The result was a Facebook Live video series called “#QuarantinewithKiani,” in which Gardner used a whiteboard to explain everything from what COVID-19 was, to how to safely re-enter the public sphere, to the importance of face masks. The campaign started food drives, distributed hand sanitizer and passed out masks. She offered step-by-step tutorials on absentee voting and helped explain personal finance in describing how best to use the stimulus checks.

And she picked up endorsements. A few weeks prior to the July 14 runoff, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren endorsed her candidacy, a rare occurrence of a national candidate paying attention to Democratic politics in Alabama’s first district. “We’re making America to stop writing off south Alabama, and that’s huge,” Gardner says. “I’m very proud of that.”

Jez, her old professor, wasn’t surprised. “Kiani’s one of these individuals who can do anything,” he says.

An academic life of service

It wasn’t just her work in the lab while a WashU student that had an impact on Gardner. When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in late August 2005, Gardner had just begun her junior year. She remembers the university taking in students from Tulane University, and the food drives and social awareness the hurricane generated on the Danforth Campus.

The next spring, she took a seminar-style class through American culture studies called “Hurricane Katrina: A Case Study in Disaster Relief,” which was team-taught and looked at the disaster from all sides. The course also included a trip to New Orleans for spring break that year.

“That was really powerful,” she says. “It was really the first time I thought that my academic life could be about service, which paved the way for where I am now.

“The following summer, I packed up my car, left my dog with a friend, and went back to New Orleans by myself to work.”

“She always had a good sense of helping other people and finding ways to give back,” Jez says. “She was constantly looking for ways to connect with people.”

‘That’s politics’

Gardner is in her kitchen a week after the runoff, in which she lost by a 57-43 percent margin to James Averhart, who will face Republican Jerry Carl in November.

“That’s politics. That’s runoffs, and why they’re so terrible for so many reasons. I am proud of the race I ran and the campaign infrastructure I put in place.”

Kiani Arkus Gardner

“That’s politics,” she says. “That’s runoffs, and why they’re so terrible for so many reasons. I am proud of the race I ran and the campaign infrastructure I put in place.”

It’s hard not to think what might have been. Gardner hints that she’s not finished with politics yet, that she’ll remain involved through November and try to help as many candidates as she can while being a mom and helping her boys navigate through the pandemic. And she’s still using her voice to educate voters, disseminating public health information on COVID-19 and encouraging blood donations.

Asked if, like that experiment in the Jez lab so many years ago, perhaps this election setback could eventually produce something bigger and better for her?

She laughs. “Yes and no,” she says. “The better analogy is one of those lab experiments in which you go where the data takes you.

“The primary election was an experiment, we got that data, moved forward. July 14 was an experiment. Got that data, moved forward. Now it’s time to chart a specific aim. Between the virus and the runoff, for a lot of people it exposed the weaknesses of our electoral system that day-to-day voters aren’t aware of.”

She’s proud of the fact, for example, that her campaign pushed hard for no-excuse absentee voting, and it will be allowed in Alabama this November. “When we did that work, a lot of people saw how difficult absentee balloting is,” Gardner says, “and how the lack of it disenfranchises communities of color, low-income communities and, in a major way, disabled communities.”

What’s more, she hopes her story might be inspiring to other women who are thinking about entering the political arena.

“I think we are inundated with stories of these amazing political successes,” she says. “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is so inspiring, but not everyone can go from bartender to Congress. So many women who aspire to national office don’t see a path for themselves, so there has to be a story that’s told that says, ‘Here’s what it looks like to get involved.’

“It pushes back against the burdensome narrative that women can have it all. You don’t have to have it all, but you can do it all because it all matters: City council. School board. Moms Demand Action. The Wall of Moms. We need narratives that are not about superstars, but just super interesting women.”

And whatever comes next, Gardner will continue to define herself by being Hawaiian, and a wife, and a mom, as a scientist — because the data is what the data is.

“It’s this really powerful idea that we live in the world we live in,” Gardner says, “and it doesn’t necessarily matter what your idea of perfect is, or what you wish had happened.

“You have to deal with what you have right now.”