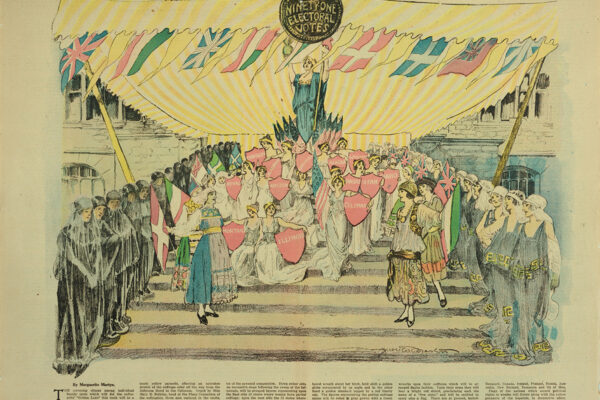

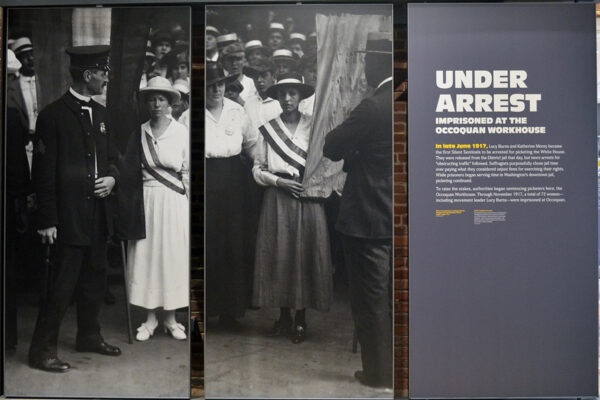

The story of women’s suffrage is long and complicated, much more complex than “Susan B. Anthony fought for the right of women to vote and won.” It’s a decades-long story of women campaigning for broader rights, and having that ultimately lead to the fight for voting rights. It’s a story of division, when many white suffragists broke from the abolitionists because they disagreed that the 15th Amendment would allow Black men the right to vote but not white women. It’s a story of exclusion, where many white suffragists pushed women of color to the margins in the march toward full enfranchisement. It’s also a story of bravery and courage, when women activists employed new tactics, such as picketing the White House, and suffered imprisonment and abuse for these strategies. It’s a story of uneven gains, where some 15 states and territories gave women full voting rights starting in 1869 (the reasons were varied and often not altruistic, such as bolstering conservative voting blocs), but where the majority of states refused.

During this 100th-anniversary year of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, it’s a story that should be explored more fully. And it’s a story that women, and men, should think about as they consider the history of voter suppression as well as present-day efforts to disenfranchise. To start the exploration, we asked four faculty members to discuss the 19th Amendment and other aspects you may not know about the long, difficult march for voting rights.

————————————————————————————————————————-

Andrea Friedman

Professor of History, and of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies

Expert on 20th-century U.S. history, including the intersections of gender, sexuality and political culture

On the one hand, we can think of the 19th Amendment as building greater democracy in U.S. history. But I think it’s really important that we not think about women’s suffrage only from a progress narrative.

“I think it’s so important to recall the ways that suffrage is about power.”

Andrea Friedman

Some women pursued the vote because they felt entitled to the same kinds of privileges of what we now call “whiteness” as the men they were related to. And so there were some white women who saw suffrage as a means to consolidate their own power as white people and as a means to maintain white supremacy. Often this had regional tones to it. The Southern States Women’s Suffrage Association was led by two women who stated explicitly that states ought to enfranchise white women to offset the vote of people whom they imagined to be less civilized. And then even after women got the right to vote, some white women used their power to uphold racial segregation. For example, making sure that they were electing school board members who were going to participate in mass resistance to the Supreme Court’s ruling of Brown v. Board of Education.

I think it’s so important to recall the ways that suffrage is about power. People see it as a means of creating power for themselves, and sometimes that’s for the good and sometimes that’s not so much for the greater good.

————————————————————————————————————————-

Rebecca Wanzo

Chair and Professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies

Expert on African American literature and culture, critical race theory and feminist media studies

It’s important to look back at social movements and try to figure out how things got done and how often the rhetorical practices and strategies do include a lot of exclusions. And that was the case with the women’s suffrage movement, where African American women are often seen as outside of it.

“Thinking through all the conflicts and the history of suffrage, which did involve Black women being thrown under the bus despite how hard they were working for suffrage, is an important part of our history and this anniversary.”

Rebecca Wanzo

But African American women played such a big role nationally, and also in a variety of states. In Illinois, for example, Ida B. Wells was very active within her own organization. Yet white women famously tried to exclude her from the 1913 suffrage parade Alice Paul organized in D.C. But Wells refused to be at the very back of the procession and joined the Illinois unit in the middle of the march.

They were really trying to push forward and make people recognize that you can’t secure the rights for women, and say that (white) women have the right to vote, when there are still all these other people excluded.

Thinking through all the conflicts and the history of suffrage, which did involve Black women being thrown under the bus despite how hard they were working for suffrage, is an important part of our history and this anniversary.

To recognize that it’s a much more inclusive history even as it’s often a story of exclusion is also important. And a lot of those exclusions are very much about how people think you can sell a social movement and get something accomplished.

Because we’re in such a high social media moment, some of the debates we are having now about representational structures and social movements — in terms of how you sell a social movement — seem kind of new. But it wasn’t an accident to have had Inez Milholland, who was like the fashion plate of the suffragists, put out there, so they could say, “See, you can be very attractive — and want suffrage!”

————————————————————————————————————————-

Travis Crum

Associate Professor of Law

Expert on constitutional law and election law, with emphasis on voting rights, race and federalism

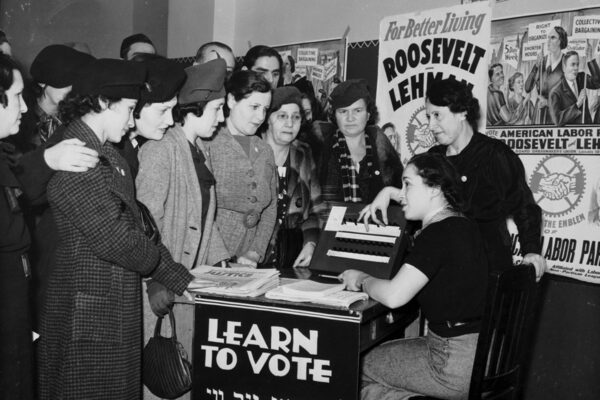

To me, the centennial of the 19th Amendment is yet another example of how our Constitution has been moving toward a more inclusive democracy. The U.S. Constitution as written in the late 1700s might have been revolutionary for its time, but it’s not a document that I think anyone in the 21st century would be comfortable signing. And the 15th Amendment — which 2020 is actually its 150th anniversary — guaranteed the right to vote free of racial discrimination. And 50 years later you have that expansion to protect women, but Black women were still being denied the right to vote in the Jim Crow South for much of the 20th century. It wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed that you actually have the right to vote guaranteed for the overwhelming majority of Americans.

“The fight continues. After the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder, where the Court invalidated the coverage formula of the Voting Rights Act, several states have enacted very strict voter ID laws.”

Travis Crum

But the fight continues. After the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder, where the Court invalidated the coverage formula of the Voting Rights Act, several states have enacted very strict voter ID laws. And these voter ID laws fall particularly hard on communities of color, because these communities are less likely to have driver’s licenses or U.S. passports. Because of longstanding patterns of discrimination, and the particular forms of IDs that are being chosen, these laws have had a disproportionate impact on communities of color.

I would also add that some of these laws have also disproportionately impacted women, because women are far more likely to change their name when they’re married than men are. And if your name on your ID is your maiden name or previous name and it doesn’t match the name that you’re registered as, or vice versa, those voter ID laws have been known to disenfranchise.

————————————————————————————————————————-

Rebecca Wanzo

Chair and Professor of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies

Expert on African American literature and culture, critical race theory and feminist media studies

I’ll add to that: I’m thinking about my grandmother and what these voter ID laws would mean for her, where there were all these records destroyed in West Virginia where she was from. She religiously voted. She always brought her [voter registration] cards but she never had a driver’s license so would have struggled to comply with laws requiring state identification.

“We want to think about why … any politician would make it harder for people to vote. The only reason … is to keep power for the people you’re aligned with and exclude others from having access to power.”

Rebecca Wanzo

There’s also the infrastructure of voting for voter suppression to think about: How many poll stations do you have? How long does it take to vote? One year I stood in line for four hours. Some of it in the rain. Not everyone can do that. Why are there always machines breaking down at my mother’s poll center? Also, voting is not a national holiday, which it is in some countries, and that makes it very hard for some people to vote, and who does that disproportionately effect?

The infrastructure of voting really impacts voter turnout, and I think one of the things we should always be aware of is that there’s this national myth about the U.S. being the place that has the best of everything in terms of freedom, and access, and resources. And even if you show people a whole bunch of empirical data that this is not the case, they still want to push the myth. So, we want to think about why it would be that any politician would make it harder for people to vote. What we want is to make it easier for people to vote. The only reason you’re going to try and keep people from voting is to keep power for the people you’re aligned with and exclude others from having access to power.

————————————————————————————————————————-

Elizabeth Katz

Associate Professor of Law

Expert on family law, criminal law and U.S. legal history, including women’s right to hold public office

The centennial of the 19th Amendment is a time to reflect on the progress women have made in securing legal and political equality, while also recognizing that this effort remains unfinished. As a law professor, I’m particularly interested in the contributions made by women lawyers. This aspect of women’s history is especially meaningful here at WashU, which was the first law school in the country to admit women back in 1869. Early women lawyers, including our alumnae, were leaders in the women’s suffrage movement at the federal and state levels. And of course, many women lawyers are active in pursuing reforms today. Most notable recently, we can look to presumptive vice presidential nominee Kamala Harris, the first woman of color ever nominated for national office by a major political party. She built her political career in large part on her service and expertise as a lawyer.

“One aspect of the women’s movement that isn’t commonly known is that suffrage was just one of the activists’ many goals. Women’s movement leaders demanded a wide range of legal, economic, social and political changes.”

Elizabeth Katz

One aspect of the women’s movement that isn’t commonly known is that suffrage was just one of the activists’ many goals. Women’s movement leaders demanded a wide range of legal, economic, social and political changes. My latest research has focused on women’s demand for the legal right to hold public office. In many states, women were ineligible for even relatively commonplace offices, such as notary public or school superintendent. Their exclusion prompted a flood of court cases, legislative debates and state constitutional amendments. Women in some states were forbidden to hold high state offices like governor into the 1940s. The 19th Amendment was truly just one step along the way toward securing women’s equality.

My research emphasizes the power of individuals to influence the law and peoples’ understandings of women’s proper role. In every state, there had to be one woman who was the first to say, “I want to hold public office, and I should be able to hold public office.” Often for legal or political reasons, she didn’t obtain that office, but that didn’t mean her efforts were inconsequential. She may have sparked some lesser change in her home jurisdiction and inspired women in other states to throw their hats in the ring. I hope people can draw modern inspiration from that history.