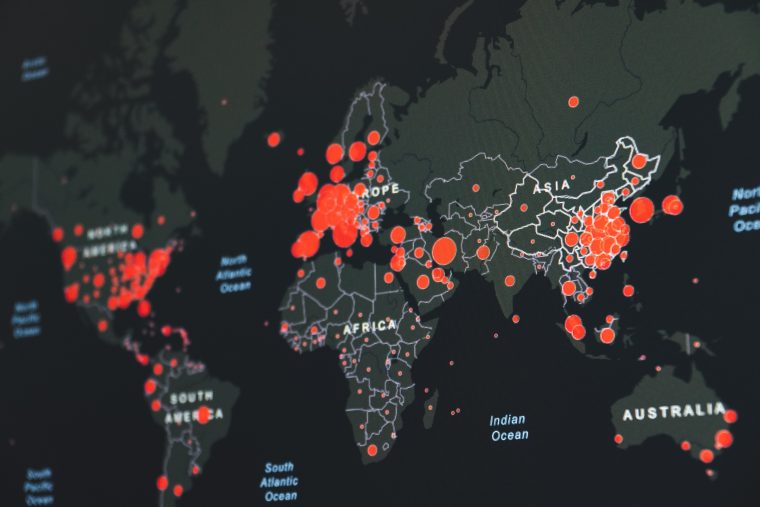

As the St. Louis region and the state of Missouri confront the coronavirus challenge, it has posed a number of serious issues for health policy analysts and health economists.

“This is the most unprecedented challenge to the health system I have seen in my career,” said Tim McBride, the Bernard Becker Professor at Washington University in St. Louis’ Brown School and a leading health economist. “Our public health systems in the region were already underfunded relative to most of the rest of the country, and people with low incomes were already facing challenges accessing medical care. This is only exacerbating the problems.”

McBride points to several challenges that have become acute in recent days because of the COVID-19 crisis:

- Low-income persons have less access to health insurance in Missouri, one of 14 states that never expanded Medicare.

“We have not expanded Medicaid, and the existing levels for Medicaid are among the lowest in the country,” McBride said. “Missouri has over 500,000 uninsured people. Uninsured persons will face significant challenges paying for medical care during this crisis, especially if they need to be tested or treated for coronavirus. The problem will only become worse if these low-income persons lose their jobs. And all this will challenge the finances of our health care systems.” - The public health systems in Missouri have long been underfunded.

“Our public health system funding ranks near the bottom in the country; we rank 44th in the U.S.,” McBride said. “This means we do not have enough funding to do the significant surveillance, testing, communications and research needed in a situation like this. Our public health departments are doing great work despite these challenges and reaching out to universities and others for help, but our systems are stretched.” - Given that we have needed to suddenly and significantly move to social distancing and strongly encourage people to stay home, this is creating a monumental economic challenge.

“We will not know until we see the numbers, but it seems certain that we will have a significant economic downturn, probably a recession, maybe a very large one in the second quarter,” McBride said. “The extent of the recession depends on how widespread the virus extends and how long policymakers continue policies to encourage social isolation. But certainly some sectors will be severely impacted: airlines, hotels, restaurants, retail, for example. And this will have a big ripple effect on the rest of the economy. We can recover from this, once people are allowed to leave home, but in the meantime, there will be losses in jobs, incomes. This only will make it more difficult to pay for medical care, especially for people who already had the biggest challenges paying for care: the uninsured, for example. What we worry about the most is that some people will forego medical care because they cannot pay, and that this will exacerbate the spread or depth of coronavirus.” - Numerous challenges to the health care workforce.

“Health economists have been worried for a while about areas where we have shortages or challenges in what we call the health care workforce,” McBride said. “The biggest areas where there are significant shortages of health care providers are nurses, mental health providers, and providers to serve those in underserved communities — that is, central city and rural areas. Unfortunately, this COVID-19 outbreak will only exacerbate these challenges and may create a crisis in some areas. If some parts of the health care workforce get sick from coronavirus, especially nurses, that will be a huge problem. If the workforce is not well distributed across the state, region or country, then we will see big shortages. For example, the big outbreaks right now are in Washington and New York, and they likely are already experiencing shortages of providers. Missouri may experience this at some point.”

WashU Response to COVID-19

Visit coronavirus.wustl.edu for the latest information about WashU updates and policies. See all stories related to COVID-19.