Many farmers struggle with an enemy that looks like a friend. Agricultural weeds that are close relatives of crops present a particular challenge to farmers because their physical similarities to the desirable species make them difficult to detect and eradicate. Along the way, the imitators compete with crops for water, nutrients and space — often depressing crop yields.

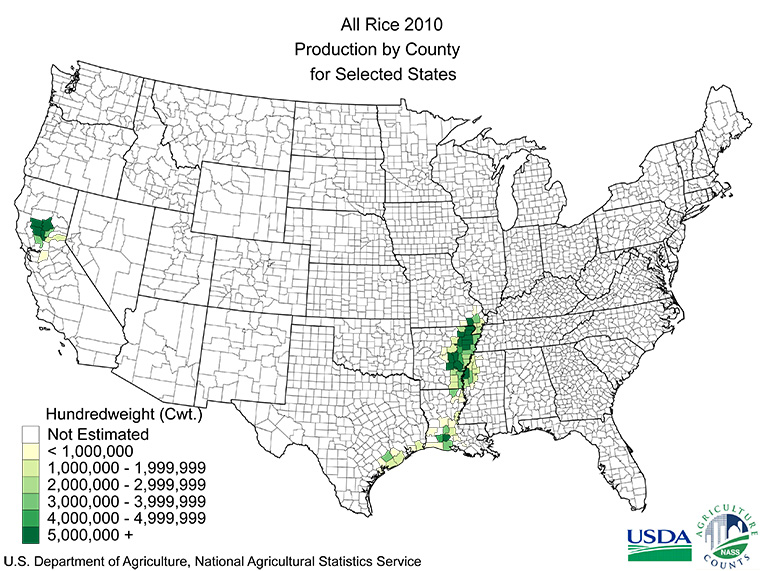

More than half of the top 10 crops worldwide are shadowed by some kind of weedy mimic. Weedy rice (Oryza sativa) is chief among them. The National Science Foundation (NSF) has just awarded $2.6 million to a team led by a Washington University in St. Louis plant evolutionary biologist so researchers can determine what makes weedy rice such a fierce competitor.

“Weeds that infest crop fields are a primary factor limiting agricultural productivity in the United States and globally,” said Kenneth M. Olsen, professor of biology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University and principal investigator for the new award. “In the case of weedy rice, the weed is essentially domesticated rice that’s gone feral.

“One of the things that always stands out to me about weedy rice is just what an aggressive competitor it is,” Olsen said. “A handful of these weedy plants per square meter can vastly decrease the productivity of the crop. If a rice field is infested with these weeds, it can reduce yields by 80% or more.”

In the U.S. alone, weedy rice costs the industry more than $45 million annually.

The new NSF funding will support research to characterize the genetic basis and origins of the traits that allow weedy rice to invade rice fields, reduce yields and contaminate harvests. The team includes investigators from the University of Massachusetts, the USDA’s Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center and the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center.

The researchers will characterize three key features of weedy rice growth and reproduction.

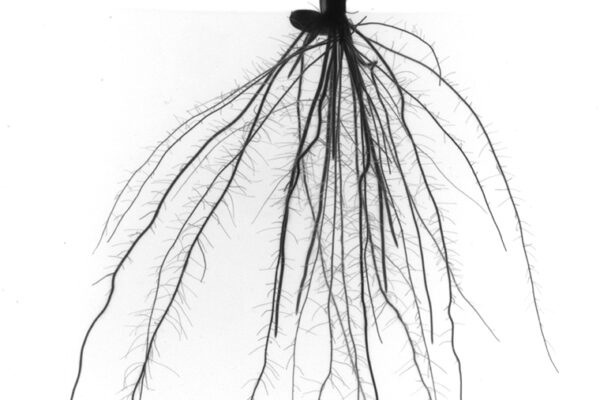

First, they will investigate the patterns of root system growth that allow the weed to outcompete rice for soil nutrients. Previous research among the team members helped reveal how weedy rice repeatedly evolved “cheater” root traits. The scientists used new imaging techniques, including a 3D optical tomography approach developed by Christopher Topp at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, to peek underground while roots grow.

https://giphy.com/gifs/washugifs-research-roots-root-js5TMt4AeFd2c0Vl0o

Previous applications of this technology were limited to tracking growth of individual plants — not the silent underground battles waged between rice plants and their weedy neighbors. The new study will line up competitors root to root for their close-ups.

“Then we can see in a more biologically realistic context how these root morphologies are playing a role in the weed competitive strategy,” Olsen said.

The new grant also will explore the genetic and developmental basis of seed dispersal mechanisms that allow the weed to rapidly invade and proliferate in rice fields. Researchers also will examine weedy rice’s differential resilience against rice blast, a common fungal disease of rice fields.

The research effort will also include training opportunities for K-12 science teachers and educational experiences for students, including deaf students — a minority group that is underrepresented in STEM careers.

Understanding how competitiveness evolves is important not only for countering noxious weeds, but also because this knowledge might someday be used to improve rice itself.

“This work could also potentially be useful for breeding more resilient crops,” Olsen said. “When these competitive traits are in weeds, we don’t like them. But if we can use some of what we learn about weedy rice for rice breeding down the road — increasing crop productivity from this information — that could be hugely valuable.”