On a gray January morning in 1545, a half-dozen workmen and twice as many oxen gathered at Michelangelo’s studio on the Macel de’ Corvi, near the hog butcher and greengrocer, and began moving Moses.

The eight-foot marble, on which the 69-year-old artist had labored for roughly half his life, was jostled through the streets of Rome, across a rutted cow pasture and around the Colosseum. At last it came to rest in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli — centerpiece of the tomb of Michelangelo’s former patron, Pope Julius II.

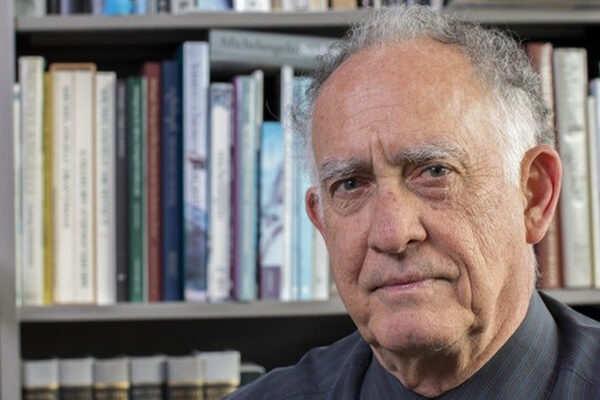

“Michelangelo lived with Moses; the two grew old together,” writes William Wallace, the Barbara Murphy Bryant Distinguished Professor of Art History in Art & Sciences, in Michelangelo, God’s Architect: The Story of His Final Years & Greatest Masterpiece (Princeton University Press, 2019).

Now, with Julius’ tomb finally complete, Michelangelo found himself at uncharacteristically loose ends, notes Wallace, the author of seven previous books about the artist. But in 1546, Pope Paul III prevailed upon Michelangelo to oversee construction of St. Peter’s Basilica. It was a monumental task.

“Everything about St. Peter’s was a mess,” Wallace points out. Begun in 1506, the church — intended as the largest in Christendom — had strayed from Donato Bramante’s original, centralized design. Bribery and graft were rampant. Progress had slowed to a virtual halt.

“From the beginning, Michelangelo knew that a building of that scale would take much longer than the number of years he had remaining on this earth,” Wallace explains. Indeed, the basilica’s massive dome would not be completed until 1590, more than a quarter century after Michelangelo’s death.

“The immediate challenge was to revive Bramante’s conception and correct its many engineering deficiencies. But this required removing much recent construction – in a sense, reversing nearly 40 years of building history. It demanded courage and vision.”

For Michelangelo, who’d outlived most of his contemporaries, and recently lost several close friends, those demands proved energizing. “St. Peter’s gave new purpose and focus to Michelangelo’s life,” Wallace writes, “inducing him to put aside his private concerns and sorrows. St. Peter’s offered a final mission and the best reason for the artist not to yield to old age, despair or death.

“Michelangelo had already accomplished much and had every right to wonder whether this was the best way to devote his few remaining years,” Wallace continues. “He never before had faced such a daunting challenge.

“Yet his salvation, he eventually came to realize, depended on resurrecting St. Peter’s.”