Critically ill children who suffer from traumatic blood loss, cancer or sickle cell disease, for example, often require red blood cell transfusions. However, research has been lacking about whether the length of storage time for red blood cells can contribute to organ failure in children receiving such transfusions.

Now, an international study led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and CHU Sainte-Justine hospital in Montreal has found no benefit in using fresh red blood cells that have been stored for up to seven days compared with using older red blood cells stored for nearly four weeks. The risk of organ failure or death in critically ill children was the same, regardless of the storage time for the red blood cells.

Partly funded by a $7.8 million grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the study is one of the largest ever performed in pediatric critical care. The research may change policies at hospitals that prefer to use fresh red cells despite the standard practice among many hospitals of first transfusing the oldest red cells in the stored inventory to minimize waste.

The findings are published online Dec. 10 in The Journal of the American Medical Association.

“Our research helps to shed light on a controversial aspect of transfusion medicine,” said first co-author Philip C. Spinella, MD, a pediatric critical care researcher and professor of pediatrics in the Division of Critical Care Medicine at Washington University. “We now have scientific evidence to reassure physicians that the standard practice of using moderately aged red blood cells is as safe and effective in these children as using fresh red blood cells.”

Spinella added that it is common for pediatric hospitals to have policies requiring fresh red blood cells for certain populations of critically ill children. For example, at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, where Spinella treats patients, the preferential use of fresh red cells applies to children who are less than six months of age, reliant on oxygen machines or undergoing cardiac surgery.

The randomized study involved 1,461 critically ill children, ages 3 days old through 16 years old, who required red blood cell transfusions at one of 50 medical centers in the United States, Canada, France, Israel and Italy, including St. Louis Children’s Hospital. The researchers evaluated data collected from patients — half girls, half boys — from February 2014 through November 2018.

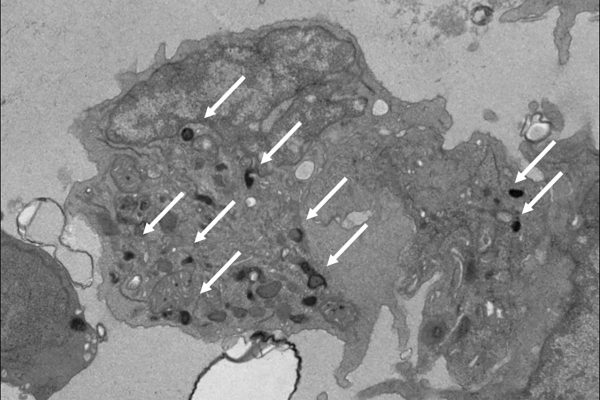

Half of the children (728) received transfusions with fresh red blood cells stored for less than seven days, while the other half (733) received transfusions with older red cells stored predominantly from 12 to 25 days. The researchers then analyzed the risk of new or progressive multiple organ failure in the children over a 28-day period or until the patients were discharged from the hospital or died.

The findings showed that children in both groups experienced similar health outcomes. Of the children who had received fresh red blood cells, 147 (20%) suffered new or progressive organ impairment or death, while the same occurred in 133 (18%) of the children who had received the older red blood cells — a difference that was not statistically significant.

“Unless extenuating circumstances exist, physicians who prefer using fresh red cells may want to reconsider,” said Spinella, director of the university’s Pediatric Critical Care Translational Research Program. “The demand for fresh red cells increases the burden on blood banks that must respond to such requests.”

One of the study’s limitations is that researchers did not evaluate red cells that are 35 to 42 days old, the longest duration allowable in the United States. Also, the researchers examined critically ill children who received low-volume red blood cell transfusions and not those requiring large-volume red blood cell transfusions.

However, Spinella noted that the study’s relatively large size and geographic diversity allow researchers to apply results to the larger pediatric population.

“This is important because there has been a global interest in determining older red blood cells’ effectiveness in critically ill children,” Spinella said. “These patients are among the sickest and most fragile.”