At city parks, local forests and even on the grounds of the Gateway Arch National Park, the creatures come out at night. And sometimes during the day, too.

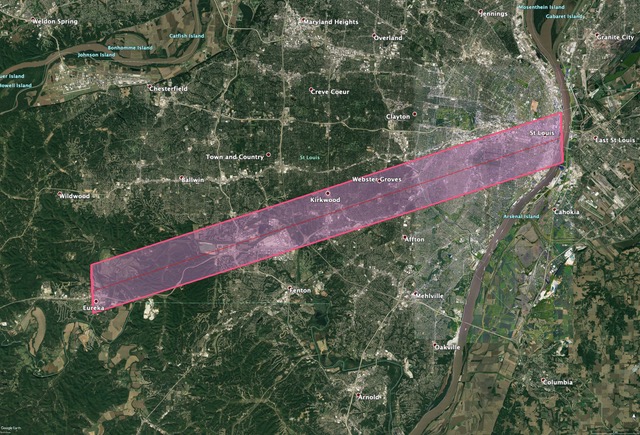

To catalogue the animal residents of urban green spaces without disturbing them, researchers have set up 34 motion-activated cameras from the densely urbanized St. Louis riverfront to the wilds of Route 66 State Park in Eureka, Mo. Four times a year, these camera traps are opened up to snap pictures of wildlife living along the Henry Shaw Ozark Corridor.

The St. Louis Wildlife Project is a collaboration between St. Louis College of Pharmacy and the Tyson Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis. The project aims to quantify biodiversity and improve the understanding of wildlife ecology in the greater St. Louis area. Through this project, St. Louis serves as a partner city in the Urban Wildlife Information Network, an initiative based at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago that includes partner cities across North America.

“Currently, more than half of the global population lives in cities, and this portion is expected to rise,” said Solny Adalsteinsson, staff scientist at Tyson Research Center. “If we are to conserve biodiversity, we need to understand how we can better plan these cities to benefit wildlife and create more sustainable cities,” she said.

One of the greatest threats to biodiversity is urbanization. However, metropolitan areas such as St. Louis can play an important role in maintaining biodiversity. Habitat patches and green spaces can support species and protect diversity in urban areas. Understanding how wildlife utilize these habitats, and interact with each other and humans in an urban environment, is essential for minimizing human-wildlife conflict.

“St. Louis is unique because we have three rivers in this region — the Mississippi, the Missouri and the Meramec,” said Whitney Anthonysamy, assistant professor of biology at St. Louis College of Pharmacy. “There’s already a lot of urban green space, and not far out of the city you immediately get into some Ozark habitats , which are also known for having a lot of species biodiversity.”

By studying how unique features of the St. Louis landscape — including rivers and parks — affect diversity and abundance of wildlife in the region, researchers can identify important elements that promote biodiversity and the coexistence of humans and wildlife.

These elements can be incorporated into sustainable design and planning for St. Louis while also informing a broader understanding of urban ecology and how best to conserve biodiversity through data-driven urban planning and development.

Students review the photos and identify the species caught on camera. So far, they have spotted squirrels, raccoons, opossums and deer — and even less common animals such as red foxes, turkeys, bobcats, river otters, skunks and armadillos.

Interested community members can volunteer for the St. Louis Wildlife Project.