Walls and fences, gates and guard towers, tents and enclosures. For migrants and refugees, the architecture of the southern U.S. border can seem as harsh as the Chihuahuan Desert and implacable as the Rio Grande.

In recent weeks, images of children locked in prison-like conditions have sparked heated debates relating to U.S. immigration policy, the role of the built environment, and the line between legitimate security and gratuitous distress. But underlying such debates is a simple question:

Is it possible to design a border architecture that is welcoming rather than foreboding?

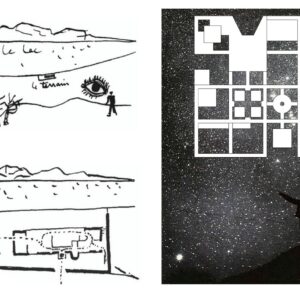

So asks Stephen Leet, professor of architecture in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. Last spring, Leet led a graduate studio focusing on the border between Presidio, Texas, and Ojinaga, Mexico. The aim was to explore how architects might create spaces and landscapes that are safe and humane while still incorporating security and processing protocols.

In this Q&A — accompanied by photos from the studio trip and renderings from students’ proposed plans — Leet discusses the studio, the state of border architecture and prospects for improvement.

How would you characterize architecture on the U.S./Mexico border?

The majority of U.S. governmental buildings are Ports of Entry at border crossings and regional Border Patrol facility headquarters. The fundamental problem is the absence of infrastructure designed to house asylum seekers.

In 2009, a Homeland Security internal review noted that “With only a few exceptions, the facilities that ICE uses to detain aliens were built and operate as jails and prisons to confine pre-trial and sentenced felons.” In 2011, ICE director John Morton pointed out that hundreds of facilities scattered across the southwest were “largely designed for penal, not civil, detention.”

So these are re-purposed buildings. They were never designed nor programmed for the housing and caring of detained immigrants. And the U.S. government has done nothing to improve conditions, nor to implement ICE’s own reform proposals.

What might a more welcoming border look like?

Perhaps the best way to answer this is to contrast the crossing at Presidio and Ojinaga. The U.S. Port of Entry is a ramshackle group of low-budget buildings and mobile trailers. The Mexican Port of Entry features newly constructed buildings designed by architects with spacious lobbies, courtyards and shaded gardens. Aesthetically, it’s akin to a small airport.

Describe your studio. How would you characterize the student proposals?

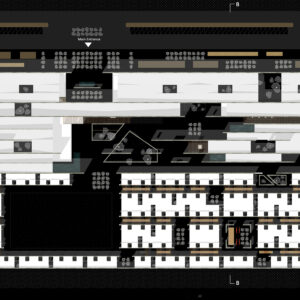

The demonization of immigrants and the preoccupation with building walls are political and cultural problems. Our studio imagined a radical shift in intention and agenda. We explored how one might design Residential Family Centers (to use ICE’s designation) that would prioritize humane treatment and care rather than barriers, incarceration and interrogation.

To do so, we researched the spaces of small towns, enclaves, monasteries and campuses. We also looked at regional courtyard housing, which is designed to mitigate arid desert climates, and 100-plus-degree summer temperatures, through shade and water retention.

One of the most difficult challenges is the need for a perimeter that detains inhabitants but also protects them from wild animals, intruders and the near-constant desert winds. One border patrol officer told us that on the day before our site visit, winds had driven burning embers from the Mexican side over the Rio Grande and into Presidio, causing several house fires.

Most of our projects incorporated the spatial and social qualities of collective housing: from the scale of the family to the scale of a community; from the dwelling and patio to the courtyard, street and plaza. The character and atmosphere are more similar to that of a small campus than a punitive detention facility.

What recommendations would you make to U.S. officials?

The worst aspects of the current situation are clear: re-purposed buildings and sites mismanaged by sub-contractors with little or no oversight. Officials should provide funding and opportunities for architects to design a whole new infrastructure — temporary housing as well as an ensemble of education, healthcare, legal and recreation facilities.

The need is absolutely urgent. A humane border architecture would provide immigrants with places of refuge and hope.

We also need to set a high bar for the quality of design, rather than simply emphasizing costs. In the future, well-designed Residential Family Centers might be re-purposed as community colleges, trade schools, even desert resorts. Good buildings can outlive their initial purpose and program.