For the past two years, Divine Umirisa has studied with other immigrants and refugees at the Nahed Chapman New American Academy at Roosevelt High School in St. Louis. She has made friends, excelled in math and science and wants to be an engineer. Impressed by her progress, her teachers say she’s ready to join the general student population.

Umirisa is not so sure.

“What if they don’t understand my English,” said Umirisa, a refugee from Rwanda. “I want to do well. That’s why I like to come here.”

“Here” is the International Institute of St. Louis, which hosts a daily after-school program that offers some 20 New American Academy students additional academic instruction, recreational activities and a place to be supported and understood.

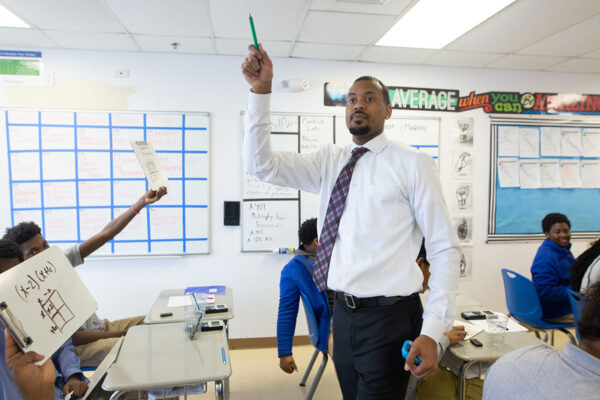

Twice a month, Cindy Brantmeier, professor of applied linguistics and education in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, and her team of graduate and undergraduate students serve the program by helping students improve their English reading.

An expert in second-language acquisition, Brantmeier has developed a social reading program that employs online gaming to meet the individual needs of each student and boosts comprehension and confidence. The results are promising.

“We have seen reading improve over time, but more importantly, they are enjoying English,” said Brantmeier, who implemented the program a year ago after developing and testing the model in her lab. “That matters because there are very serious, negative long-term implications for adolescents who do not reach an advanced level of English proficiency. Reading in English is fundamental to everything these teenagers do daily in high school across all content areas.”

The students hail from Afghanistan, El Salvador, Kuwait, Mexico, Uganda and other nations. At home, they may speak Spanish or Pashto or Swahili. But here, they speak English. Quite well, actually.

And yet, most read at a fifth grade level or below. That’s pretty good considering they arrived only recently with little or no English. Still, these students must make substantial gains in reading comprehension if they are to earn their high school diploma before aging out of the education system at 21.

“I have always challenged the validity, reliability and fairness of high-stakes standardized testing, but I put these issues aside to help the immediate needs of these local high school students who want to achieve high scores on the state exams,” said Brantmeier, noting that oral proficiency does not correlate with the ability to read. “If we can improve their reading, we can improve their immediate academic progress in high school and hopefully decrease the overwhelming pressure these students experience.”

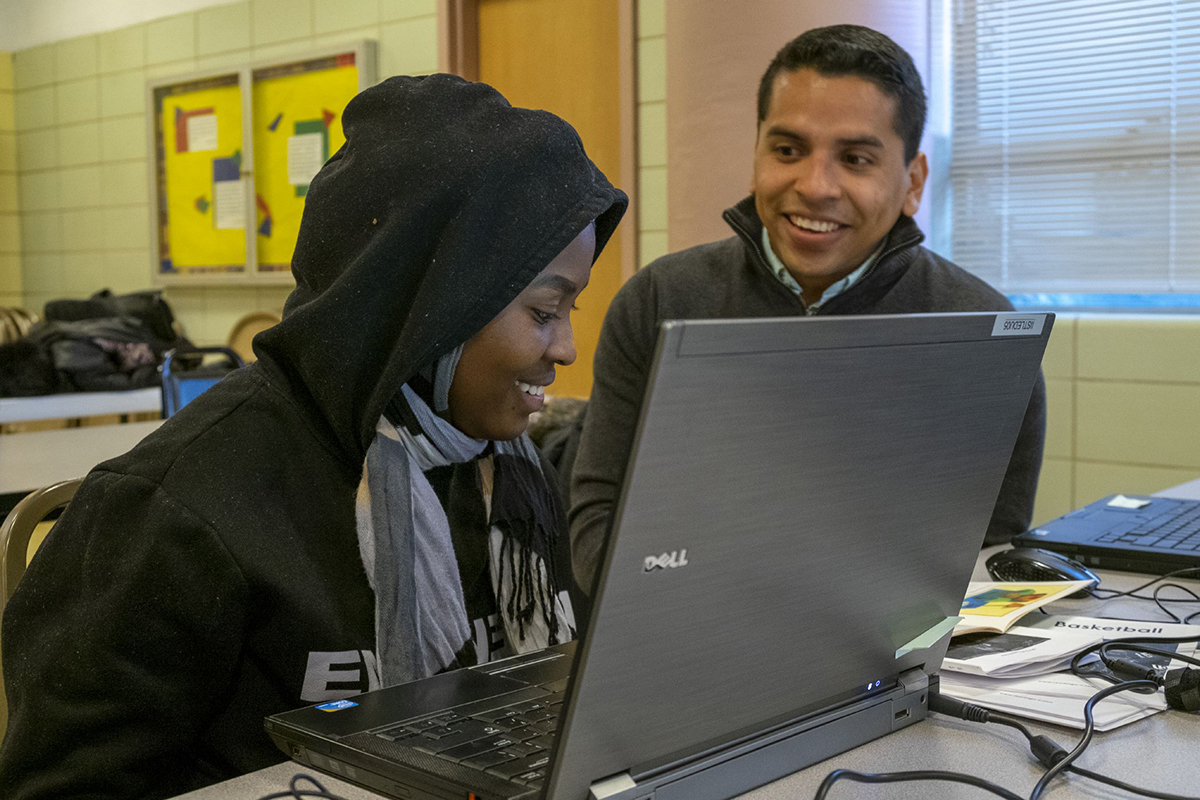

On this day, Umirisa is working with David Balmaceda, a PhD student in Brantmeier’s class “Literacy Across Languages and Cultures: Theory, Research and Practice.” Balmaceda gets these students; English is not his first language, either. Raised in Nicaragua, Balmaceda was Umirisa’s age when he took his first English class.

“Some researchers will tell you that is too late,” said Balmaceda, who wanted to study English so he could make money as a tour guide. “But I believe it is never too early or too late to learn a second language. These students are proof. They are so motivated to learn.”

Balmaceda directs Umirisa and her partner, two of the more advanced students in the group, to read “The Art of Being a Cat,” a silly book about a finicky feline. Leveled for fifth-grade readers, the book includes fairly complex sentences and concepts. After they complete the reading, Umirisa and her partner open their laptops and compete in an online game that gauges how well they understood the story.

“True or false,” Balmaceda asked. “Wind-up toys can be fun once in awhile.”

“What is ‘wind up,’” Umirisa inquired.

Momentarily stumped, Balmaceda struggled to find the words to explain. So he mimed the act of cranking a key and then scurried his fingers across the table.

Umirisa entered “no.” Her partner pressed “yes.” Before revealing the answer, Balmaceda asked the students to explain their answers and identify context clues.

“See, it says that cats should play with spools of thread and to not to settle for boring toys,” Balmaceda said. “You are correct, Divine. Good job.”

Brantmeier said the online competition, though fun for students, matters less than the conversations.

“After every question, the students use their own words to explain why they select the answers they did,” Brantmeier said. “So we are attending to individual differences but doing it collectively and socially. The more they get to know us, the more they take risks and ask us questions.”

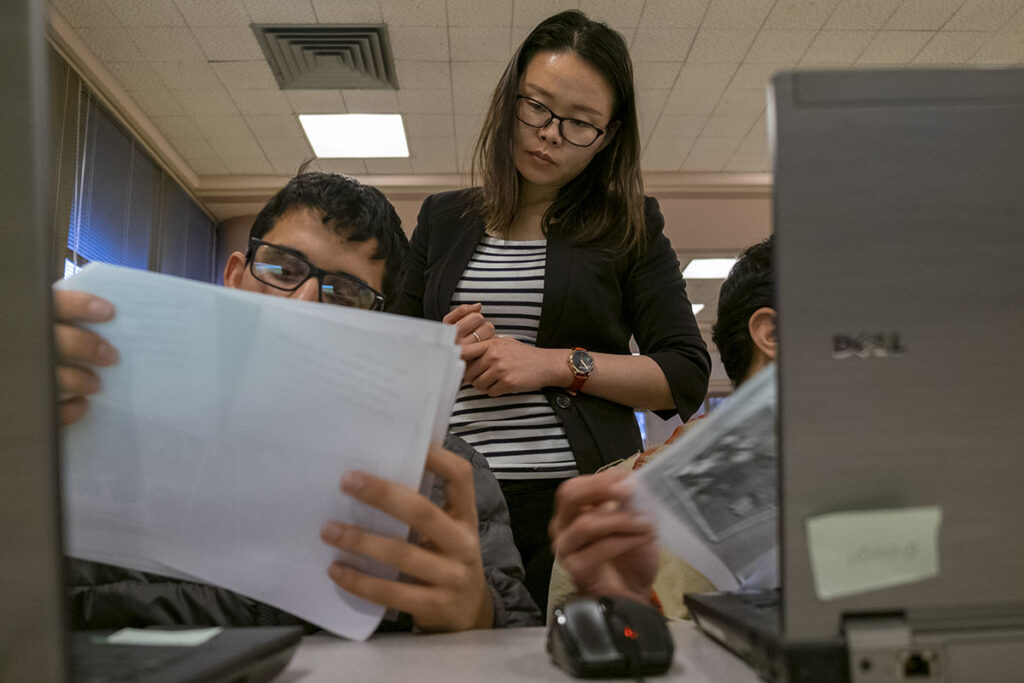

At the next table, PhD student Yanjie Li, a second-language learner from China, helped two boys from Afghanistan read “Let’s Make a Pie,” a considerably easier book with bigger pictures and fewer words. Though the students have lived in America as long as Umirisa, their reading is less advanced. Brantmeier’s research explains some reasons why.

“My work and that of others in my field has shown that with adolescents and adults, 50 percent of one’s ability to read is accounted for by first-language literacy and second-language knowledge,” Brantmeier said. “For the last decade, I have been conducting a series of studies across languages that examine the other half of the equation — how transient variables, such as anxiety, self-esteem and self-confidence impact one’s ability to read in another language.”

With some students, trauma also plays a role, as upheaval and war have impacted their education, Brantmeier said. In future semesters, she plans to continue training other volunteers to implement the online social reading program while continuing to investigate how factors such as anxiety, linguistic background and cultural values play a role in reading. The results could change how state policymakers and educators support these new Americans.

Balmaceda is excited to support the research and serve as a role model to these students.

“Not being American ourselves, we can say, ‘It’s not easy, but it is possible,’” Balmaceda said. “It’s good for them to see, especially today, that there are people who want to help them.”