You don’t need to be a great coder to teach computer science. You only need to be a great teacher.

That is the experience of Jaime Gilligan of Washington University in St. Louis’ Institute for School Partnership (ISP). Through the Code.org professional learning program, Gilligan and other ISP instructional specialists are teaching local middle and high school teachers with no computer science experience to lead computer science courses.

“The Number One thing I hear from administrators is that they can’t find any computer science teachers to hire,” Gilligan said. “I tell them, ‘Send your art teacher, your theology teacher, your math, science or social studies teacher. That teacher will be able to learn computer science. And because they know how to teach, your students will learn computer science too.”

The need is urgent. Missouri employers are struggling to fill more than 10,000 open computer science jobs, according to Code.org, Washington University’s partner and a leading advocate for computer science education. And that number will grow as artificial intelligence and robotics radically reshape our economy. Yet only 35 percent of Missouri’s high schools offer a computer science course.

To close the skills gap, Missouri just enacted a new law that creates computer science standards; allows high school computer science credits to count toward graduation requirements in math, science or practical arts; and supports professional development.

“Improving our workforce is a top priority with this administration, and in order to help move Missouri forward, we need to expand opportunities for our students,” Gov. Mike Parson said when he signed the bill in October.

At the University City School District, Superintendent Sharonica Hardin-Bartley already established a rigorous computer science curriculum. Three of her instructors are enrolled in the Code.org professional learning program.

“The results have been great for our teachers and our students,” Hardin-Bartley said. “ISP’s approach, which positions the teacher as the lead learner, not the sage on the stage with all of the information, shifts that cognitive load to the students and gives them more voice and input.”

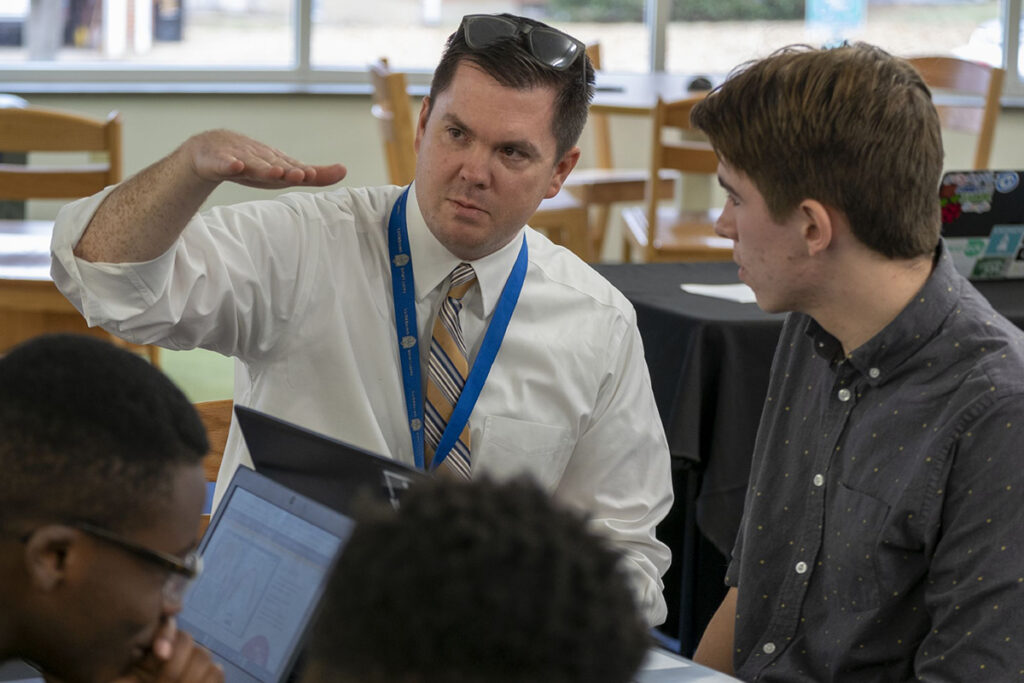

Earlier this month, University City computer science teachers and students gathered in the high school library to participate in Hour of Code, an annual computer science event. Across the globe, students of all ages tackled various Hour of Code challenges, from designing a typeface in JavaScript to mapping stars in Quorum. ISP developed a uniquely St. Louis coding challenge: redesign the Gateway Arch using the visual programming language Scratch.

Teacher Emily Knight was there with her AP computer science students, many of whom zipped through the challenge. One student created an Arch made of copper; another altered the monument’s shape. Knight said some of her students know more about computer science than she does. And that’s OK.

“We learn together, which is way more impactful than me just lecturing the students,” said Knight, a veteran math teacher. “It’s great when one of my students explains a concept to the class or helps another student figure out an error in their code.”

Gilligan has a similar story. She was teaching theology at Ursuline Academy when she took her first coding class at LaunchCode. At the time, she was considering a career switch. But the more she learned, the more she wanted to share her knowledge with her students. Gilligan started a “Girls Who Code” club and then developed a coding course for credit.

“It was great because my students were having so much fun, but I was out there on my own without a lot of support or resources,” Gilligan said. “What I needed was a program like this.”

Gilligan currently is recruiting the program’s second cohort. The teachers will spend a week in the summer at Washington University learning core computer science concepts and then will meet quarterly. Teachers will stay in touch throughout the year, swapping lessons and offering support.

The same model has proven highly successful for ISP’s acclaimed MySci program, which provides K-8 teachers professional development as well as an award-winning science curriculum and corresponding instructional materials. Last year, the MySci curriculum reached 50,000 elementary and middle school students in 2,000 classrooms.

“We know that providing teachers with vetted curriculum and resources and access to a community of learners is key to their success in the classroom,” Gilligan said. “With the right preparation, they can do anything.”