Frankenstein created his monster with body parts plundered from morgues and the graveyard. For her monster, student Sarah Adcock employed a less scarce, yet still scary material: wax.

“Wax is a material I use in almost all of my works because of its ephemeral quality,” said Adcock, who is pursuing a master’s in fine arts at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. “It especially worked for this project because it allowed me to evoke flaking, almost rotting skin.”

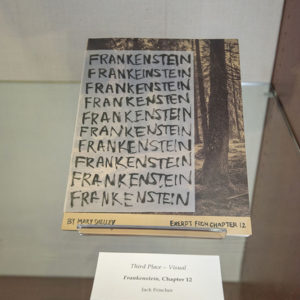

Adcock is one of the winners of the Monster Challenge, a contest sponsored by the Frankenstein Bicentennial, Washington University’s ongoing celebration of Mary Shelley’s novel and its enduring legacy. Students created sculptures, paintings, books, musical compositions and works of fiction that reimagined Frankenstein’s monster for the 21st century. Their work is now on view in Olin Library’s Gingko Room.

For her piece, “Vaccus,” Adcock sewed a muslin bodysuit using her own body as a model. She then dipped the body suit in hot wax over and over again.

“The process was almost ritualistic,” Adcock said. “It took a long time, but that’s how I got the appearance of skin sloughing off.”

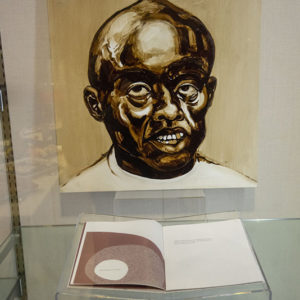

Student Greg Bailey, another Sam Fox MFA student, also used a nontraditional material for his painting “Blackstein”: tar. The work is a portrait of a black man with a disfigured skull and gold teeth.

“There is a monstrous relationship among the materials — the black tar, the solvent which I used to strip away the tar underneath his eyes, the gold leaf in teeth,” Bailey said. “Yes, he looks like a monster because no skull looks that way. But the way the materials behaved almost violently with each other is what really interested me.”

Patricia Olynyk, director of the Graduate School of Art, served as a judge of the Monster Challenge, along with Buzz Spector, professor of art, and Jan Tumlir, lecturer, both at the Sam Fox School. Olynyk said the works powerfully captured the novel’s core themes.

“These works conjure all of the right questions and ideas,” Olynyk said. “The human desire to augment or transform the human biology; the question of whether evil is socially constructed or whether it resides in the body; how this piece of literature still resonates today — it’s all here.”