If you want to start a food fight among restaurant aficionados in St. Louis, ask about the origins of toasted ravioli.

It’s the kind of question that animates visitors to the website Lost Tables and its companion Facebook group. Both were started by Harley Hammerman, AB ’71, MD ’75, HS ’79, a radiologist with many interests. Along with being president of Metro Imaging, a company he began nearly 25 years ago, Hammerman is a specialist in American playwright Eugene O’Neill as well as in local bygone restaurants.

Yet, it’s the vanished restaurants — their menus, their signature dishes and, most of all, their memories — that have captured the attention of thousands of others, current and former St. Louisans. And Hammerman thinks he knows why.

“We don’t want to grow up,” he says, “so it’s a way of remembering our past and trying to stay young. I sometimes wonder if I could have pulled off the Lost Tables idea in another city or not. I was going to try it in New York City or Kansas City, then it occurred to me that you would have had to grow up in a city to know its restaurants over time.

“I wonder whether it’s like ‘Where did you go to high school?’ — which is, of course, a very St. Louis thing — that we always remember where we used to go to eat.”

The apple of his eye

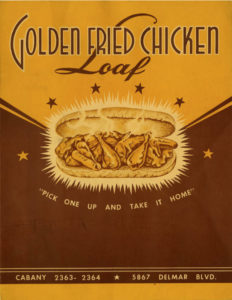

For Hammerman, the memories began with a long-gone restaurant on Delmar, east of the U. City Loop: Golden Fried Chicken Loaf.

“It was one of the restaurants that has always haunted me,” he says. “That fried chicken might not taste the same to me today, but in my mind it is what all fried chicken has been measured against.”

By chance, he located the granddaughter of Mina Evans, the restaurant’s original owner. He thought of doing a whole website just about Golden Fried, but he realized there might not be enough meat there.

Then, bitten by the history bug, he started to wonder about and research other fabled restaurants he loved and missed.

Next up were Cyrano’s, the basement bistro on Clayton Road in the DeMun neighborhood that featured a decadent dessert known as the Cleopatra, and Ruggeri’s on the Hill, famous for veal parmesan, showy service and organist Stan Kann. For Hammerman, both spots brought back memories of dating his high school sweetheart, who would later become his wife.

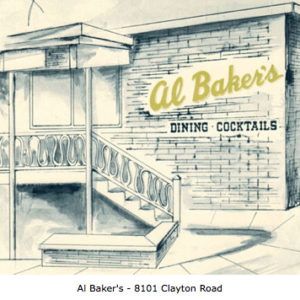

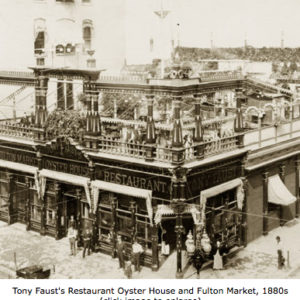

With his restaurant appetite whetted, he created Lost Tables, and the range of establishments you can find at the site amazes. They range from the casual to the fancy, from Hamburger Heaven to Tony Faust’s. Alphabetically, they stretch from Al Baker’s to the Zodiac Lounge.

“These were not necessarily the best restaurants in the world,” Hammerman says, “but they provided the best memories.”

For Washington University graduates, their memories of familiar eateries will vary depending on the time they spent at the university — and whether they were enrolled on what is now the Danforth Campus or farther east at the Medical Center.

Do you remember Santoro’s, at the corner of Big Bend and Millbrook, or do your thoughts wander back to Bobby’s Creole or Rinaldi’s in the Loop? If you spent more time in the Central West End, what comes to mind when you hear about the Red Brick or Kopperman’s?

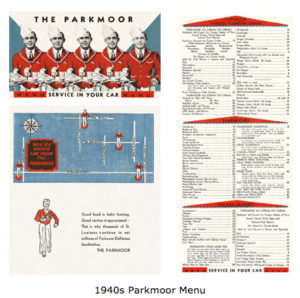

Probably everyone, however, remembers the spot down Big Bend that Hammerman says draws by far the biggest reaction.

“Parkmoor blows the rest away,” he says. “It’s mind-boggling how much more interest that restaurant has generated than the others. Perhaps it’s because many of Parkmoor’s clients were related to the university somehow.”

His cup of tea

Hammerman’s love of history and collecting was apparent even before he created Lost Tables. An expert on Eugene O’Neill, Hammerman became interested in the playwright when he took Wanda Bowers’ English class at University City High School. He remembers Bowers beating on the tom-tom when the class studied O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones.

Further, when the annual Book Fair was held on the parking lot of the old Famous-Barr in Clayton (now the site of the university’s West Campus), Hammerman would show up early, looking for first editions, like the one he found of Ah, Wilderness!, one of O’Neill’s rare comedies.

From there, Hammerman began studying rare book catalogues, and as his collection grew, people with memorabilia began contacting him. Now, he has autographed books, letters, manuscripts, photographs, theater programs and other ephemera. For his 50th birthday, Hammerman’s technically savvy children gave him a domain so he could build a website for the archive, eoneill.com.

At the site, he chronicles the life of one of the greatest American playwrights, a Nobel laureate in literature, who Hammerman says is pretty much ignored in schools these days. However, the site attracts a variety of followers.

“There are academicians who are reviewing it for themselves,” he says, “and the people who act and write and just love the theater and love O’Neill for his plays. They’re the ones who love the website.”

Previously in 1988, Hammerman helped plan a centennial celebration of O’Neill’s birth at the university. And, more recently, he began looking into transferring his entire collection to Washington University, mainly because of their shared interest in the playwright’s life and works.

Bread-and-butter issues

As Hammerman winds down his involvement with O’Neill, he also is taking on a different role at Metro Imaging, the firm he founded with other radiologists in 1994. At that time, he says, with the advent of managed care, it was time for a new model to provide the MRIs, CT scans and other images patients need.

“Things were changing in medicine,” Hammerman says. “It used to be that insurance companies threw money at hospitals. Then managed care came along.”

Stressing service and lower cost, the firm grew to five locations throughout the St. Louis area. He credits a helpful staff — the kind of friendly people you would find working at Disneyworld, he says — with its role in the company’s success.

“It’s not the equipment, and it’s not the radiologists,” he says. “It’s our staff members who have made us successful.

“I call the staff and sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to them on their birthdays. Over the years, I find that more and more of them are taking the day off on their birthday,” he laughs.

As he and his partners started growing older, they began looking for an exit strategy. They found a buyer in Mercy, the health system headquartered in St. Louis. The deal was formalized in spring 2018, but Hammerman says it won’t change Metro Imaging’s competitive spirit, which has tweaked hospitals for their prices and sometimes sluggish response times.

“We still make the decisions,” he says. “We still buy the equipment. Nobody’s signing off on it. We’ll just keep doing everything the way we’ve been doing it.

Food for thought

“I don’t play golf. I don’t play cards with the guys. This keeps me off the streets, yet engaged with folks and with history.”

— Harley Hammerman, MD

So with his business sold and the O’Neill collection about to change hands, Hammerman is concentrating on Lost Tables. It takes time to track down memorabilia, write articles and answer the questions that come up regularly on Facebook. But it’s clearly a labor of love.

“I don’t play golf. I don’t play cards with the guys,” he says. “This keeps me off the streets, yet engaged with folks and with history.”

And lest we forget about the eternal question of who created the St. Louis delicacy known as toasted ravioli, the issue arose once again recently among the Lost Tables Facebook group, and Hammerman directed people to the story told by longtime Ruggeri’s waiter Mickey Garagiola — brother of former big-league catcher and broadcaster Joe Garagiola.

Mickey Garagiola insisted that t-ravs began when Fritz, a cook at the old Oldani’s restaurant on the Hill, accidentally dumped some boiled ravioli into the deep fryer, and a new taste treat was born.

Other visitors to the Facebook site insisted toasted ravioli started elsewhere, with Mama Campisi, Mama Toscano, the Gitto family, Lombardo’s and other contenders. Probably the truth lies in the post of one visitor, who said:

“Pretty much every restaurant on the Hill claims to have invented t-ravs.”

It’s an answer that’s shrouded in history, just like the restaurants in Hammerman’s Lost Tables.