Often viewed as wild, naturally pristine and endangered by human encroachment, some of the African savannah’s most fertile and biologically diverse wildlife hotspots owe their vitality to heaps of dung deposited there over thousands of years by the livestock of wandering herders, suggests new research in the journal Nature.

“Many of the iconic wild African landscapes, like the Mara Serengeti, have been shaped by the activities of prehistoric herders over the last 3,000 years,” said anthropologist Fiona Marshall, the James W. and Jean L. Davis Professor in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis and a senior author of the study.

“Our research shows that the positive impacts of increased soil fertility in herder settlement corrals can last for thousands of years,” Marshall said. “The longevity of these nutrient hotspots demonstrates the surprising long-term legacy of ancient herders whose cattle, goats and sheep helped enrich and diversify the vast savannah landscapes of Africa over three millennia.”

The study, which focused on wildlife hotspots in Kenya, documents how the cultural practices and movement patterns of ancient herders and their livestock continue to influence an array of seemingly wild and natural phenomena.

“Ecologists have suggested that wildlife movements, including the Serengeti’s famous wildebeest migrations, may be influenced by the location of nutrient-rich soil patches that green rapidly during the rains,” Marshall said. “Our research suggests that some of these patches may be the result of prehistoric pastoral settlement in African savannahs.”

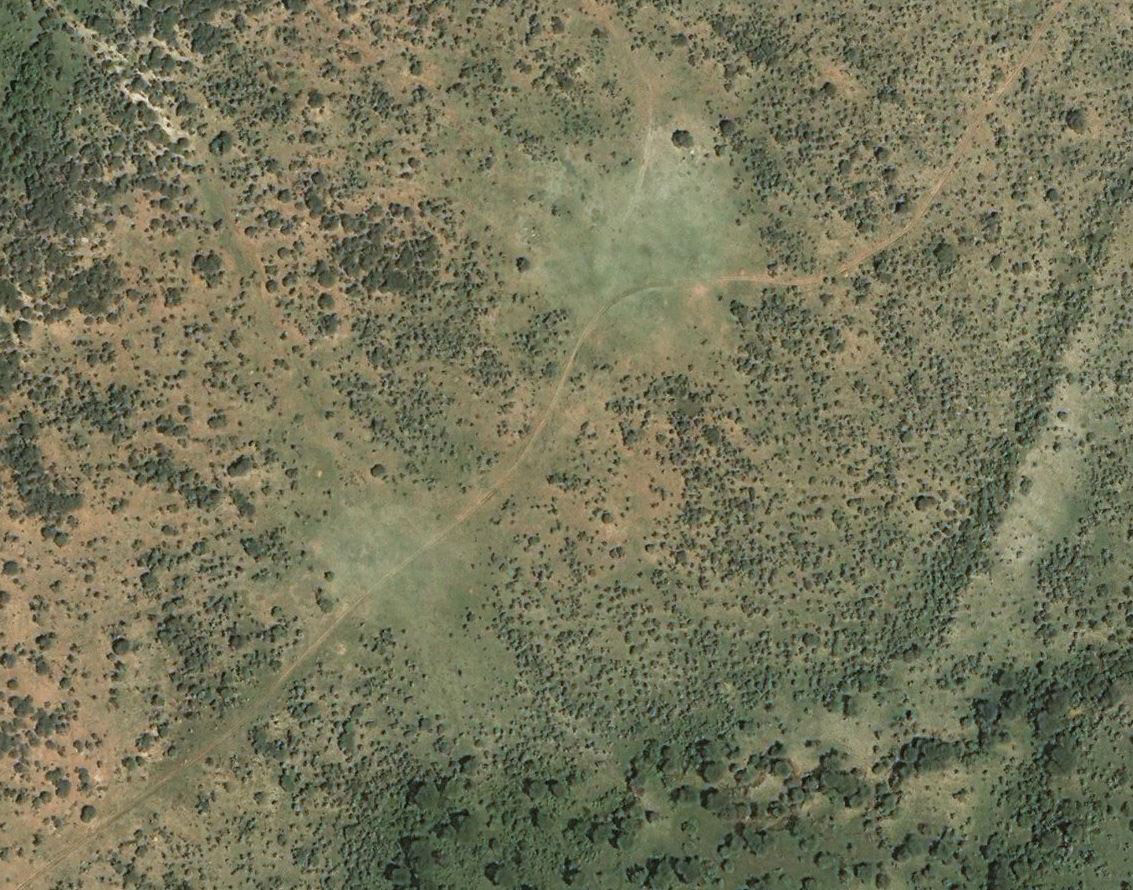

Based on satellite imaging and detailed analyses of soil nutrients, isotopes and spatial characteristics at ancient Neolithic herder sites in East Africa, the study offers a surprisingly simple explanation for how oval-shaped wildlife hotspots measuring about 100 meters in diameter evolved in a region where grasslands are naturally low in soil nutrients — manure happens.

For millions of wildebeest, zebras, gazelles and the carnivores who hunt them, migration patterns revolve around an age-old quest for the lush grasses that spring up on fertile soils after seasonal rains.

While other research has shown that fire, termite mounds and volcanic sediments may contribute to the varying fertility of savannah soils, this study confirms that ancient livestock dung has long been an important catalyst in an ongoing cycle of soil enrichment — one that continues to attract diverse wildlife to the sites of abandoned livestock corrals.

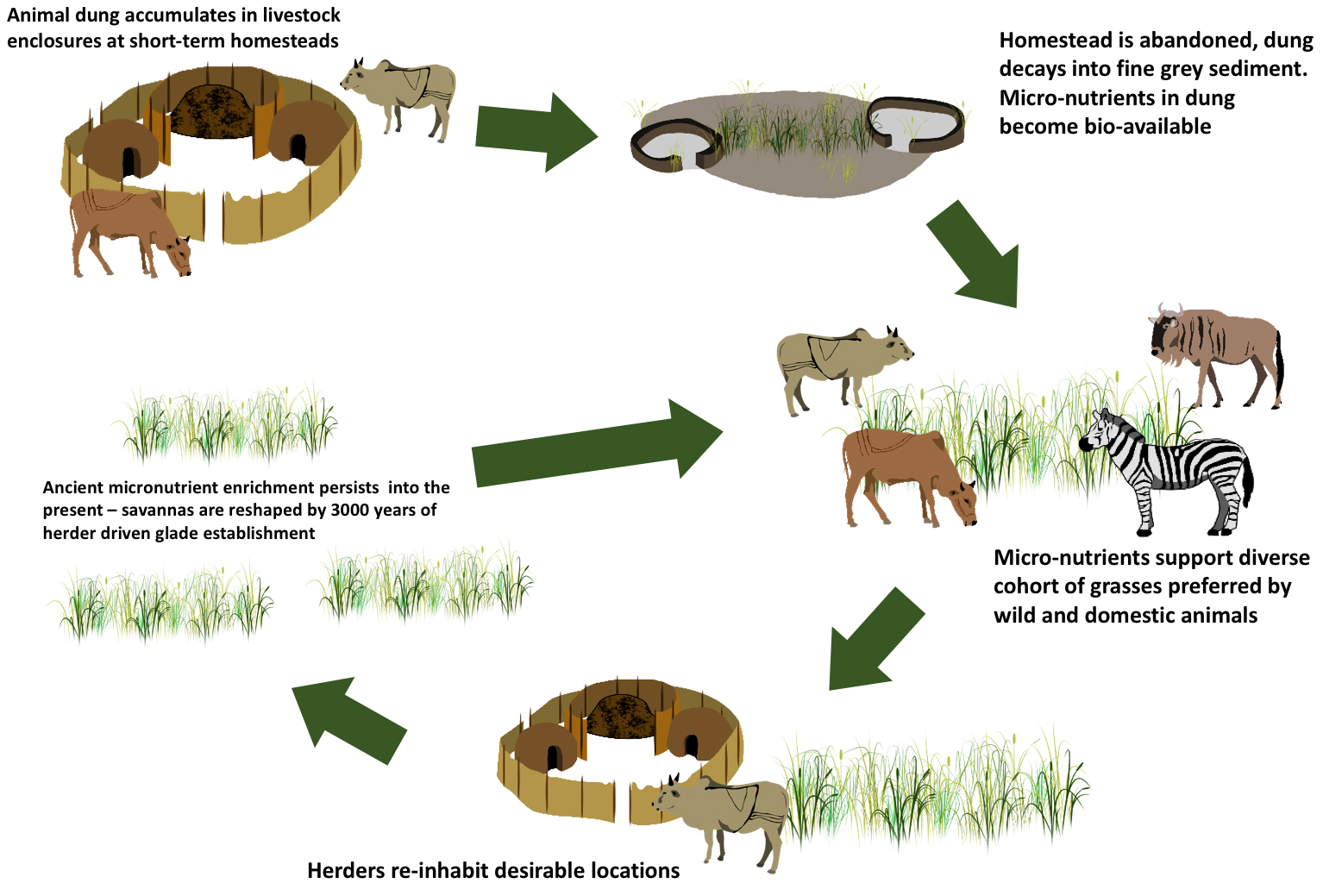

For 2,000-3,000 years, savannah grasslands of southwestern Kenya were occupied by groups of nomadic herders who moved their camps often in search of greener pastures. Livestock that grazed the open savannah by day were herded into small, oval-shaped corrals within settlements at night for protection from predators and rustlers.

As manure piled up in these temporary corrals, scarce nutrients from surrounding grasslands also began to accumulate, creating fertility hotspots that attracted herds of both wild and domesticated grazers for years to come.

Thus, over the millennia, the cultural practices of mobile herders had the unintended consequence of creating spatially stable fertile environmental niches for an array of wildlife, the study contends.

While the herding activities of mobile communities of modern and historic Maasai and Turkana have been shown to enrich savannah soils, little has been known about the lasting impact of Africa’s earliest food producers, herders who moved south from the Sahara 2,000-5,000 years ago.

This study examined five Neolithic pastoral sites in southern Kenya, ranging in age from 1,550-3,700 years, and found that the sites still contain nutrient-rich sediments resulting from livestock dung deposited as far back as 3,000 years.

As compared to the surrounding savannah, ancient pastoral sites were found to have significantly higher levels of phosphorous, magnesium, calcium and other nutrients essential for plant growth and animal health and reproduction.

Observed from the ground and via satellite, these ancient pastoral sites appear as treeless, open grassy patches within larger expanses of wooded savannah grasslands. Excavations show that the abandoned settlement footprints are loosely defined by a visually distinct, fine-grained layer of grey sediment, now located about a half-meter below the surface and up to a foot thick in places.

Over the millennia, the increasing fertility of these ancient settlement sites have increased the spatial and biological diversity of savannahs.

Ecological research by scholars such as Robin Reid at Colorado State, Truman Young at the University of Californa-Davis and colleagues has shown that in fertile corral soils, grasses tend to out-compete woody vegetation, creating open glades of nutritious grasses where grazing animals are also less vulnerable to predators.

Wild herbivores that forage there, such as gazelle, wildebeest, zebra and warthog, exert a positive influence on plant productivity and nutrient turnover. Hotspot fertility generates rapid plant regrowth after rains and provides essential nutrients for pregnant and lactating herbivores.

High fertility soils also means more soil invertebrates — worms, dung beetles and other insects, which, in turn, attract more of the birds, reptile and elephant shrews that feed on them. As shown in a 2013 study, a species of gecko that thrives in these nutrient hotspots is virtually non-existent in the open savannah between them.

By establishing the role that the early herders played in enriching Africa’s savannah soils, this study by Marshall and colleagues in Nature offers yet more evidence for the entwined nature of human activities and other ecological influences on the landscapes in which we live.

In the United States, recent studies have shown that early Native Americans used fire to manipulate the migration patterns of buffalo herds, changing the climate and ecological balance of the Great Plains in the process. Researchers suspect that ancient pastoralists also may also have influenced grassland ecology in pastoral regions of Central Asia and South America.

Back in the Serengeti, research has shown that the modern wildebeest migrations also contribute to the redistribution of scarce savannah nutrients as they drown or fall prey to crocodiles while crossing the Mara River. Their dead bodies add large quantities of phosphorus, nitrogen and carbon to the river ecosystem each year.

In showing that ancient herding sites may still be influencing modern wildebeest migrations, research by Marshall and her colleagues also is relevant to ongoing debates over the impact of livestock grazing on biological diversity and wildlife survival in grasslands, both in the Serengeti and around the globe.

“Ecologists have shown that when present-day herders are mobile and live at relatively low densities, they have few long-term negative impacts on the environment and some significant positive ones,” Marshall said. “Our findings provide a new perspective on how human herding activities have influenced, and sometimes enriched, the ecology of African grasslands. From a policy perspective, it suggests that there are ecological costs to increasing sedentization of herders.”