As the United States celebrates its founding on July 4, new research on “collective narcissism” suggests many Americans have hugely exaggerated notions about how much their home states helped to write the nation’s narrative.

“Our study shows a massive narcissistic bias in the way that people from the United States remember the contributions of their home states to U.S. history,” said Henry L. “Roddy” Roediger, professor of psychological and brain sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis and senior author of the study.

The study, published June 24 in the journal Psychological Science, is based on a national survey of nearly 4,000 U.S residents, including about 50-60 respondents from each of the nation’s 50 states.

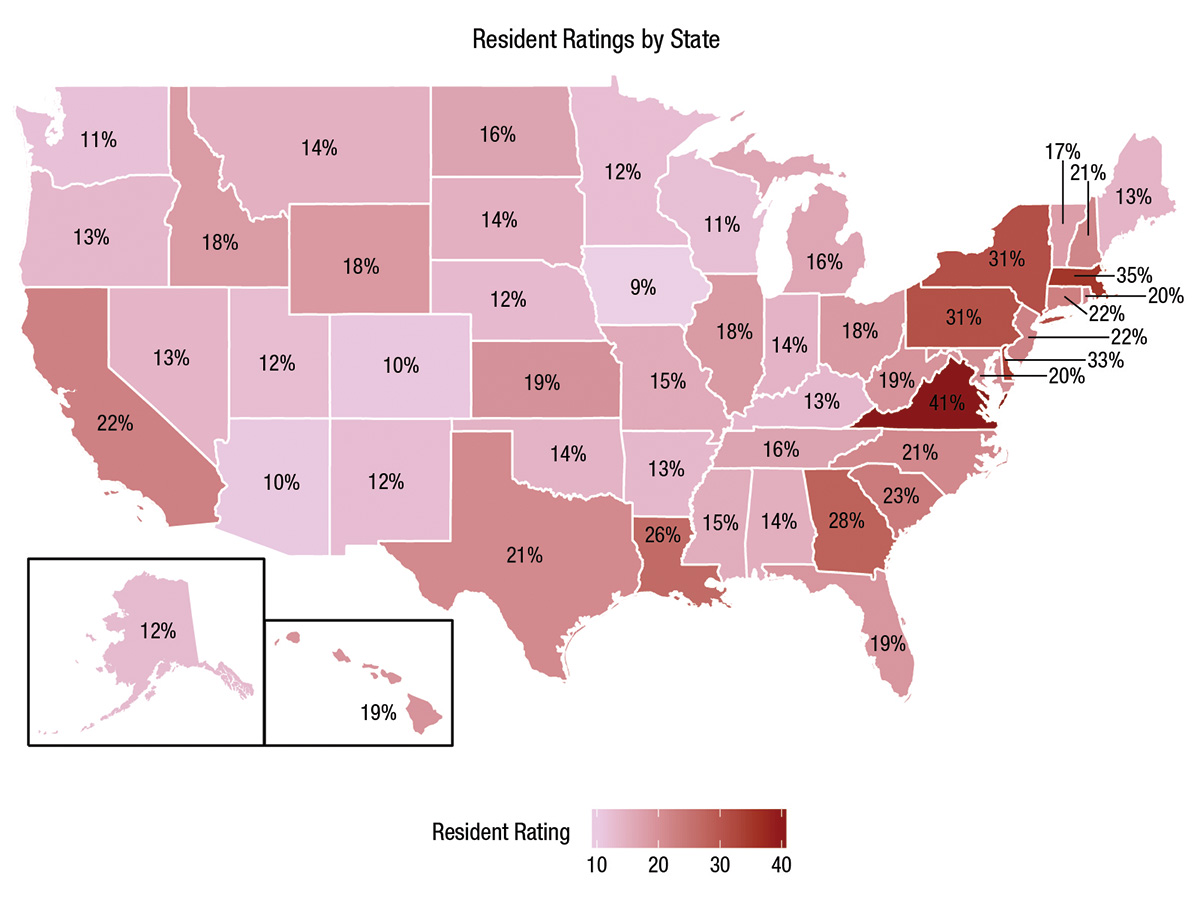

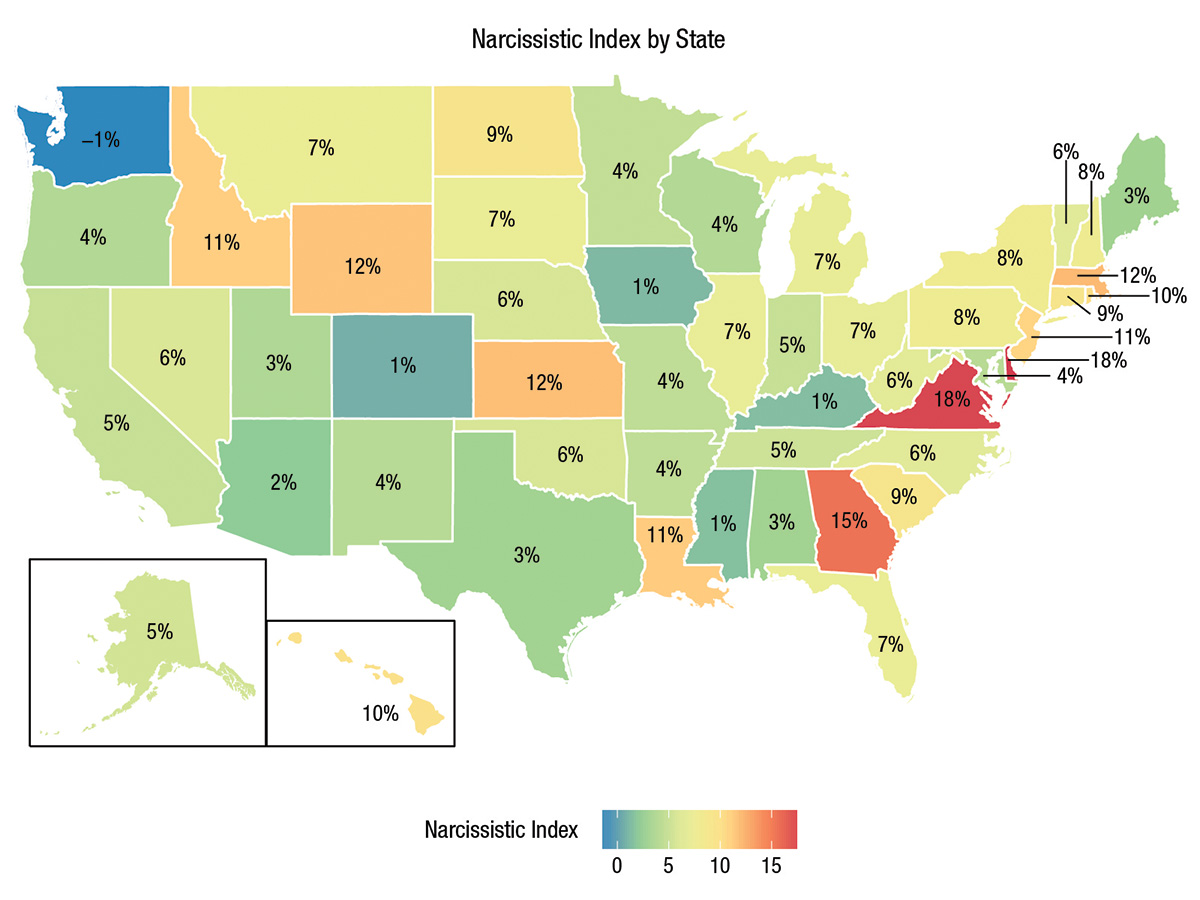

Asked to estimate their home state’s contribution to U.S. history, participants routinely gave their home state higher scores than those provided by non-residents of the state.

“As we originally hypothesized, the original 13 colonies, Texas and California showed high levels of narcissism, but there were also some surprises,” said Adam Putnam, the study’s first author and assistant professor of psychology at Furman University in South Carolina. “For example, people from Kansas and Wyoming thought much more of their state than nonresidents.”

Collective narcissism — a phenomenon in which individuals show excessively high regard for their own group — has been studied extensively in smaller social circles, such as workplaces and communities. Psychologists have explored the idea that people over-claim responsibility for shared tasks for a long time, but this study is among the first to research its effects among huge virtual groups of loosely connected individuals scattered across entire states.

While it is difficult for anyone to accurately estimate an individual state’s contribution to the nation’s history, it is mathematically reasonable to expect the sum total of individual state contributions to add up to a figure in the vicinity of 100 percent.

Instead, the average percentage contributions estimated by residents of each state in this study added up to a staggering 907 percent, more than nine times higher than logic suggests.

Roediger grew up in Virginia and was not surprised that his home state was on the high end of the continuum, claiming responsibility for 41 percent of the nation’s history.

“We would study U.S. history one year, then Virginia history the next. Many of the events are the same: Jamestown, the Revolution, four of the first five presidents being from Virginia, all the Civil War battles,” he recalls.

When people in other states were asked about Virginia’s percentage contribution to U.S. history, they also gave a high number: 24 percent.

In an effort to see if state narcissism could be reduced by exposure to the realities of U.S. history, researchers divided the sample into two groups, requiring half to take a quiz designed to remind them of the true breadth of U.S. history before they answered the relevant question. The other half answered the question first, before they took the quiz. However, placement of the question about how much the person’s state contributed did not matter. The average across the 50 states was 18.1 percent whether the question was posed first or was placed last.

“The responses are even more amazing because we explicitly tell people in the question that there are 50 states and the total contribution of all states should equal 100 percent — even with that reminder Americans give really high responses,” Putnam said. “Being reminded about the scope of U.S. history before making the estimate doesn’t seem to lower the responses.”

Putnam, who earned a doctorate in psychology from Washington University in 2015, has worked with Roediger on other studies of collective narcissism, including a just-published paper that applies the same methodology to 35 nations around the globe.

That study, which found that residents of Malaysia considered themselves responsible for 39 percent of world history, has important implications for how residents of these countries view one another and interact on the world stage.

Roediger and Putnam offer several explanations for the skewed perceptions uncovered in the study of collective narcissism among residents of American states.

For starters, people know a lot more about their home state than other states: they study state history in school, visit museums and so on. All of this information comes to mind quickly and easily compared to information about other states (a phenomenon known as the availability heuristic).

A second factor is that social psychology research has clearly shown that people like to associate with successful groups and think of themselves as being slightly above-average on a variety of positive traits.

Finally, people might not be particularly good at making quantitative estimates about small numbers.

“The most important take away from this research is that people may appear to be egocentric or narcissistic about their own groups, but there isn’t necessarily anything malicious or evil about it — it is just the way we view the world,” Putnam said. “There is certainly concern about tribalism in today’s culture, so this project is a nice reminder to try and think about how people from different backgrounds see things.”