Have you ever confused a coffee cup for a pen? Or a mango? Or your Aunt Beatrice?

Of course not. Sure, maybe you once poured coffee into your cereal. But that’s because you were distracted or sleepy, not because you saw a coffee cup and thought “milk.”

Keith Hengen, assistant professor of biology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, is wowed by the organizational prowess of our brains. How, he wonders, do hundreds of millions of neurons interact reliably time after time, especially given that the proteins that power neurons have half-lives on the order of seconds to hours?

“And yet, a cup is a cup,” Hengen said. “You are, in essence, saying, ‘We are going to rebuild this Lego castle constantly, and it’s always going to produce the same architecture. We can add new Legos — say the concept of a travel mug — but it’s still going to rebuild this same castle. We don’t know where that set of instructions lies. We don’t know how it is that the brain can possibly continue to rebuild the same structure over time and not destroy itself.”

Hengen is determined to find out. But to do that, he must collect a lot of data. And by a lot, we mean 20 terabytes a day — more than any single lab at Washington University.

“We’re generating a Netflix-sized database every month,” Hengen said.

In the latest installation of WashU Spaces, Hengen offers a tour of his groundbreaking neuroscience lab.

“There is nothing traditional here,” Hengen said. “We have raised a lot of eyebrows.”

Hengen modeled his lab after the collaborative work spaces he visited at Google, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Microsoft Corp. and the University of Washington. He returned to Washington University committed to key design features — movable furniture, a collaboration space that is separate from the wet lab and really good coffee.

“At Brandeis, my desk was in a wet lab, which meant closed-toe shoes, no food, no coffee, nothing,” Hengen said. “So, several times a week, we would go get coffee — a process that would take forever. The human capital that you are losing is huge. Here, you can have a good coffee or, at 7 p.m. on a Friday, have a beer. It’s all about having dynamic spaces that are modular, collaborative and comfortable.”

When Hengen’s researchers aren’t slurping coffee or debating homeostatic mechanisms, they are writing code, dissecting data — or sleeping in adjoining quiet workspace.

“Part of the reason we picked these couches is that they are comfortable for sleeping,” Hengen said. “There is never foot traffic through this space, so we know, as a group, that if someone is in here, leave them alone.”

Barrage of data

For years, scientists have collected data from a single neuron by inserting a super-thin wire into the brain of a mouse. The technique earned scientists Erwin Neher and Bert Sakmann the 1991 Nobel Prize. The Hengen lab takes the work to the next level by collecting information from thousands of neurons at once.

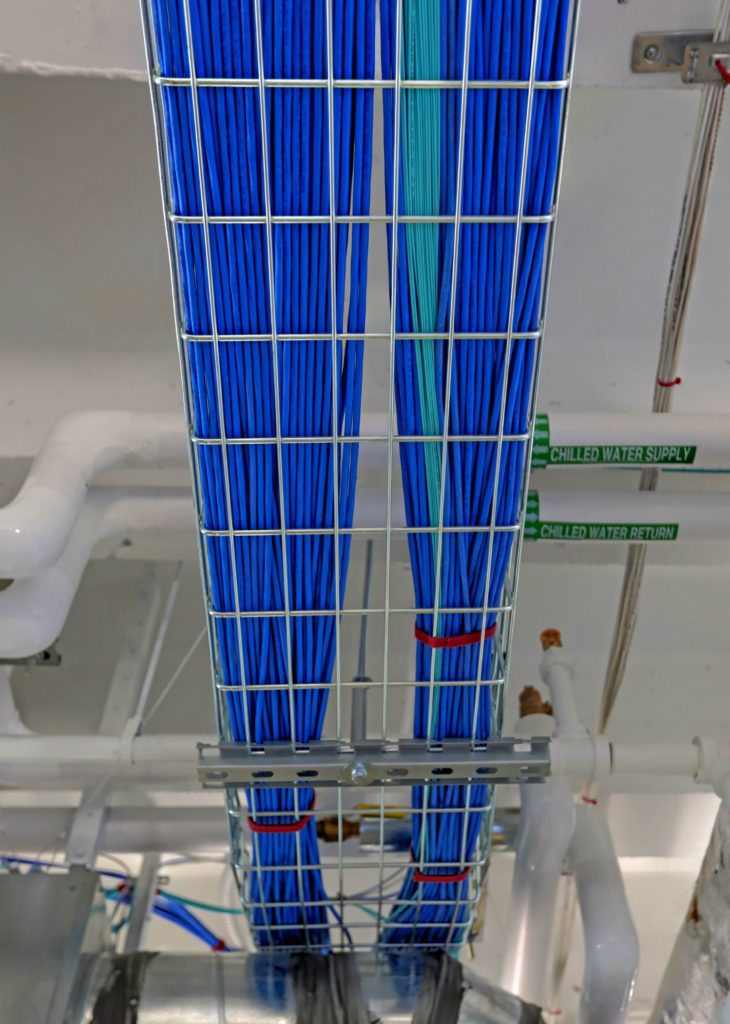

And with that leap comes a barrage of data. To accommodate the 20 terabytes of data the Hengen lab collects every day, as well as the future needs of other university labs, crews had to lay down fiber-optic connections along Forest Park to connect the Danforth Campus to high-performance computing clusters at the School of Medicine.

“Typically, scientists record for a few hours,” Hengen said. “What we’ve figured out how to do is record for weeks at a time so we can figure out how the same neuron integrates information through sleep, through wake, through light, through dark, across aging, across disease progression.”

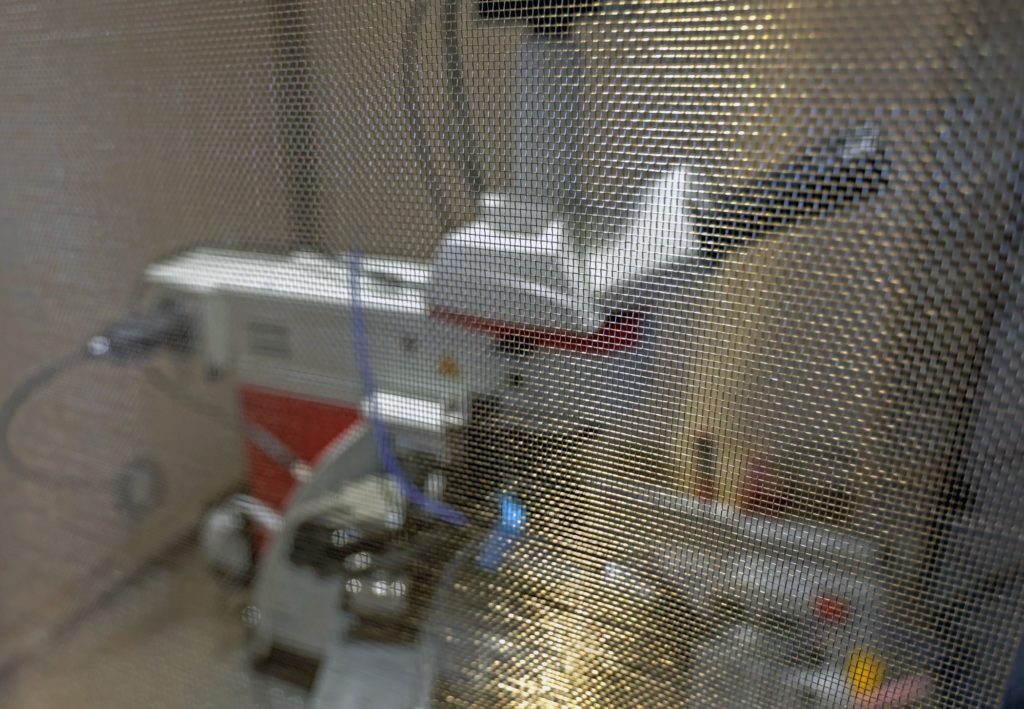

All of that data is captured by a super-sensitive recording device. Wire mesh, known as a Faraday cage, has been placed around the device and into the drywall to guarantee that no stray electrical signals from, say, a text message or phone call corrupt the data.

“We are recording microvolts, and in order to do that, you have to isolate the external world,” Hengen said.

Hengen’s lab boasts its own makerspace with a laser cutter, laser printer and electronic workstations to build custom plexiglass mouse enclosures that can be equipped with sensitive monitoring devices. The big upfront investment will save hundreds of thousands of dollars in the long run, he said.

“There will be cameras with night vision and devices that detect pressure changes when the animal moves. We’ll also know when a mouse goes to its water bottle or food,” Hengen said. “All of that will be connected to computers with artificial intelligence that can tell us how the animal is interacting, what it’s doing. It’s all automated.”

Studies show that people with the most experience or the loudest voices tend to drive conversations. Hengen did not want that for his lab, and he brought in Fisher Qua, who has helped NASA and other organizations create a non-hierarchical culture. Hengen’s team has a voice in all decisions, from lab coats (his team likes tie-dyed) to computer code.

“It is very important to me that there is no hierarchy,” Hengen said. “Which is, of course, paradoxical because I am using my authority to say I don’t want authority.”