In an attempt to get people up and moving, health experts have gone beyond recommending a walk or gym membership: Now, they’re pairing with civil engineers, architects and city planners to create environments that are not only conducive to physical activity, but also encourage it.

Public health officials can set activity goals. Architects can design buildings. Civil engineers work with city planners to make spaces more walkable and bike-friendly. When it’s all said and done, though, what is the measure of success when it comes to designing a healthy environment?

Amy Eyler, associate professor in public health at the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis, led a team that has answered just that question.

They designed a study — and made a toolkit available to the public — to measure the effects that a deliberately designed environment can have on physical activity, the environment and collaboration.

The construction of a new building presented the opportunity for a “natural experiment,” one in which a change in the environment had the potential to affect health outcomes.

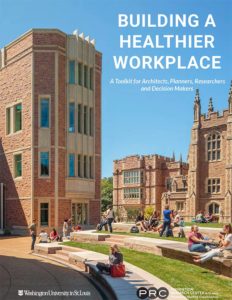

“Hillman Hall was built to be healthy,” Eyler said of Thomas and Jennifer Hillman Hall, the newest academic building on Washington University’s Danforth Campus. “Architects were purposeful in creating an environment that would enhance physical, mental and social health,” as well as a space that was environmentally sustainable and fostered collaboration.

For example, in Hillman, people were encouraged not to have waste bins or printers in their offices, Eyler said. Instead, the building incorporated centrally located spaces for these items. “This forces people to get up every now and then and walk down the hall to print or throw something away,” she said.

This not only gets people moving, but it also increases the odds of running into a co-worker and striking up a collaboration. Fewer printers also may mean fewer ink cartridges, as people become more selective about what they print.

Eyler and her team of researchers from the Prevention Research Center — Cheryl Valko, associate director, and Ramya Ramadas and Marissa Zwald — along with Aaron Hipp, associate professor of community health and sustainability at North Carolina State University, used accelerometers to monitor activity levels before and after employees moved into Hillman Hall.

They also surveyed workers about their physical activity and their satisfaction with their workspaces. The novel study setup had many moving parts, and involved recruiting participants, procuring accelerometers and more. “This was one of the first studies of its kind with this methodology,” Eyler said.

But when Eyler talked about the study to a group of architects, she learned that there were additional hurdles yet to cross. “I presented the results of a study at an architecture conference and it was clear,” she said, “We need to learn each other’s language to talk meaningfully about this.”

So Eyler and her team got to work on a toolkit. That toolkit outlined their methodology, best practices for use of accelerometers, information on writing surveys, employing observers, holding focus groups and more.

“It’s all written in a straightforward, simple way,” Eyler said, “so that people outside of public health can take advantage of our work, too. These are complex problems.” But the toolkit aims to make it a little easier to evaluate the solutions.