You won’t ever hear Anthony Tillman, assistant provost for student success, describe low-income students as “disadvantaged.” To him, a student’s low-income status is a not hurdle but a hallmark of strength.

“You got here because of all of the things that make you who you are,” Tillman said. “No student should ever feel like they have to sublimate their background and history.”

In 2016, Tillman and Harvey Fields, assistant dean for student success, launched Deneb STARS, a cohort program that provides community and support to low-income students. It’s a segment of the population that often reports feeling left out on a campus where students wear Canada Goose parkas and vacation abroad during break.

Tillman was never that “vacation abroad” kid. His parents were teenagers who did not complete high school. He took his first plane trip at age 17, when Purdue University flew him out to campus. Fields, who grew up in rural Georgia, also was a first-generation, Pell grant-eligible student at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

Tillman and Fields’ personal histories helped shape Deneb STARS (Sustaining Talented Academically Recognized Students), which is named after the farthest star visible to the naked eye. But so did their years of experience in higher education, studying and implementing strategies to retain students. The end result: a program where low-income students socialize and study together, learn leadership skills and support the next generation of students.

Oscar Gomez is one of 129 first-year Deneb STARS and an architecture major in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. He lives in Chicago but grew up in Mexico City, where he developed a passion for colonial architecture.

“Traveling from the outskirts into the center of the city is like traveling through time,” Gomez said. “The closer you got, the older the architecture became.”

Gomez, a first-generation college student, enrolled in the Sam Fox School to learn how architecture can support social change. Each Wednesday, he meets with Ruth Durrell, a sophomore from Milwaukee and his peer mentor. Durrell is majoring in educational studies in Arts & Sciences, so she can’t help him with specific architecture assignments. That’s the job for the program’s 24 academic peer mentors. Rather, Durrell is both a coach and big sister. On this day, she reminded Gomez to go to office hours and to visit Student Health Services for his stubborn cough.

“I tell my Denebs, ‘You need to take advantage of everything campus is going to give you because you are never going to have resources like this again. You need to make your professors work; it is their job to help you. You are not here to struggle by yourself,’” Durrell said.

“I understand what they are going through. I feel that some students who are more affluent understand, ‘Hey, I paid for this; I deserve this help,’ versus a kid on scholarship from a public school who doesn’t want to feel like they are inconveniencing a professor,” she said.

Durrell is an Ervin and Enterprise Holdings Scholar, not a Deneb STAR. But as the program ramps up, Tillman has recruited low-income students such as Durrell to serve as peer advisers.

“I can’t even explain what it’s like to have a community where you don’t have to explain why you can’t go out to dinner to a nice restaurant or go shopping,” Durrell said. “I’m very proud of my low-income, black, queer identity, and I remind my mentees they should be proud of who they are, too.”

Sarah Matney, a pre-med student in Arts & Sciences, is another one of Durrell’s mentees. Matney grew up in the affluent resort town of Coronado, Calif. Many of her classmates were accepted to elite universities; most could pay the full cost. Not Matney.

“I cried twice during the application process — once when I got my admissions letter to WashU, and then again when I got my scholarship package,” Matney said.

Matney looks forward to the monthly Deneb cohort meetings. On this night, Lucy Chin, coordinator of student success projects and a 2017 graduate, invited young alumni to share with the Deneb students their paths to success. There was a designer, an entrepreneur and a software developer, but Matney zeroed in on Sarah Turecamo, a 2017 graduate who is now a research assistant at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Matney asked Turecamo how she found physicians to shadow, and how many medical schools she will apply to. Afterward, Matney and cohort members learned how to manage stress with a university counselor who, like them, was a low-income student at a highly selective university. Then, it was time for pizza.

“In the past hour, I’ve met a really successful researcher and learned you can visit a therapist on campus for free, and I got dinner,” Matney said.

Provost Holden Thorp likes what he is hearing from these students. When the university committed in 2015 to boost the Pell-eligible student population from 7 percent to 13 percent, he knew there would be an abundance of talented applicants. The bigger challenge would be dismantling the obstacles that stand between students and a true Washington University experience. Some barriers are financial, such as not having the money to study abroad or to buy a lab coat. Others are cultural, like not knowing what to expect on a college campus or feeling excluded. Thorp said Deneb STARS is just one initiative designed to serve the growing number of low-income students.

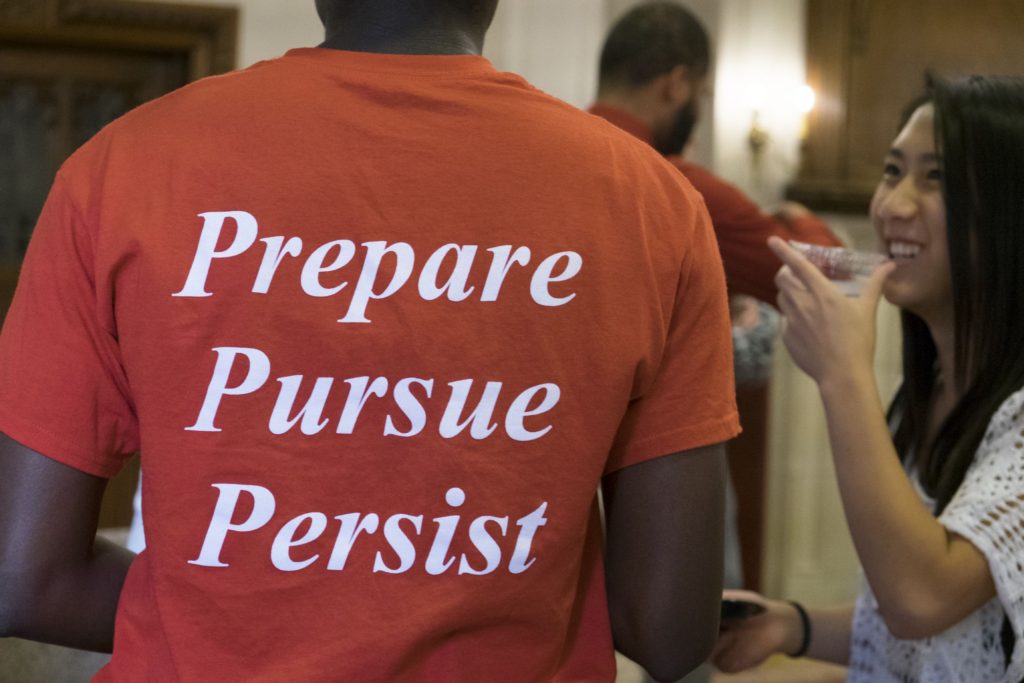

“We know a sense of belonging is a very strong determinant of how people feel about their college experience,” Thorp said. “One of my biggest hopes for this program — and I see it happening — is we’re now seeing students who are excited to say they are part of Deneb, wearing their Deneb T-shirts. We’ve got a long way to go, but we’re making the turn from students feeling excluded to feeling proud of this group.”