Jonathan Barnes, assistant professor of chemistry in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, was among 18 leading young researchers across the United States honored Oct. 16 as a 2017 Packard Fellow.

He is the 10th faculty member at Washington University to receive this prestigious fellowship in the program’s 29-year history — and remains dazed by it all.

“There are about three or four chemists nationally each year to get named,” Barnes said. “It’s a huge honor. If you look down the list of the previous fellows, it’s actually humbling to be part of that list. There are people who have been Nobel laureates. People who will be Nobel laureates.”

“This is a well-deserved recognition of an outstanding young scientist, and I could not be more impressed and delighted,” said Barbara Schaal, dean of the faculty of Arts & Sciences and the Mary-Dell Chilton Distinguished Professor. “It’s particularly gratifying to see this award go to a chemist as we are in the midst of an exciting investment in, and transformation of, that department.”

Schaal noted the university’s “strong track record now with this career-changing-fellowship,” with three consecutive Packard Fellows: Barnes; Gregory Bowman (2016), assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics at the School of Medicine; and Arpita Bose (2015), assistant professor of biology in Arts & Sciences.

There have been four in the past seven years, dating to David Fike (2010), director of environmental studies in Arts & Sciences and associate director of the International Center for Energy, Environment and Sustainability (InCEES). Another previous winner, Jonathan Losos (1994), currently at Harvard University, was named last month to head Washington University’s new Living Earth Collaborative. Still another, Provost Holden Thorp (1991), personally sent Barnes a congratulatory email. “That felt cool,” Barnes said.

The Packard Foundation, via half of the famed Hewlett-Packard partnership that resulted in successful international companies admittedly derived to an extent from university lab research, established this program in 1988. The aim: to provide early-career scientists with flexible funding and freedom to explore new frontiers in their field.

Barnes, who began working at the university July 1, 2016, considered it long odds to win the award. With 50 U.S. universities each considering by his estimation 50 young professors in their first few years on faculty for only two slots to represent a school in the competition, he likened it to a lottery — with a five-year, $875,000 prize attached.

“Basically, it’s people in their third or fourth year on faculty, getting ready to go for tenure, who contend for this award,” Barnes said. “It’s super competitive. It was a long shot, but it paid off.

“I’ll be honest: My approach to this was very aggressive. I hired two postdocs right away: Angelique Greene and Xuesong Li. It helped. Because those two postdocs, along with graduate students Abigail Delawder and Kevin Liles plus undergraduate Mary Danielson, generated a lot of data. We ended up getting it primarily based on that.”

And perhaps it didn’t hurt that his application also included recommendations from chemistry department chair Bill Buhro, the George E. Pake Professor in Arts & Sciences, and 2016 Nobel chemistry co-winner Fraser Stoddart of Northwestern University, Barnes’ doctoral adviser. Barnes also expressed gratitude for the efforts of Katherine Kornfeld, senior associate director in foundation relations, who assists with such awards.

The grant, he said, will go toward continued lab work in the area of hydrogels, “soft actuator” polymers and attaining his ultimate goal of creating artificial molecular muscles. In less than 15 months’ time at Washington University, Barnes and his group of postdocs and students have produced findings for two papers in progress.

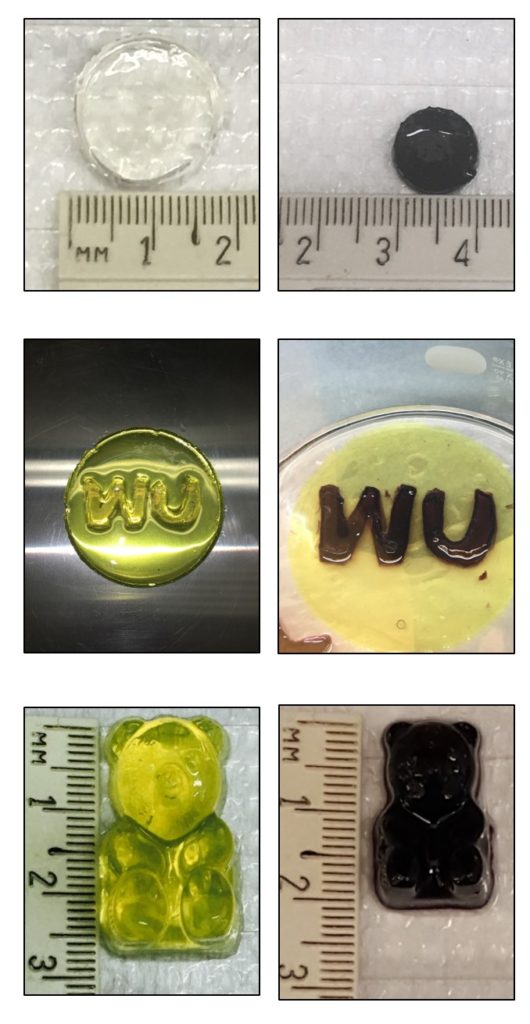

Working with 3-D materials on a centimeter scale, they use electrons and other ways of changing the size and shape of hydrogels, a gelatin-like polymer consisting mostly of water. Using their own proprietary blend, they have been able to contract hydrogels to 1/10 their size and volume. However, to Barnes, the next, big step is to elicit such reactions from stronger, larger and more dense materials — such as a rubberish polymer (elastomer) that someday could help to produce fast-acting prosthetics and more.

“That’s where the field needs to be, that’s the holy grail of this field,” Barnes said. “We’re still a long way from it.”

Barnes, a native of Louisville, Ky., earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Kentucky, and his PhD at Northwestern. After a postdoctoral fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he accepted an offer to work at Washington University and moved closer to his Kentucky home.

Barely 15 months later, he joined a group of less than 600 scientists and became a Packard Fellow. Said Barnes: “I’m still in disbelief.”