The tomb of a Maya ruler excavated this summer at the Classic Maya city of Waka’ in northern Guatemala is the oldest royal tomb yet to be discovered at the site, the Ministry of Culture and Sports of Guatemala has announced.

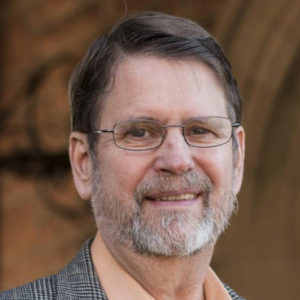

“The Classic Maya revered their divine rulers and treated them as living souls after death,” said research co-director David Freidel, professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

“This king’s tomb helped to make the royal palace acropolis holy ground, a place of majesty, early in the history of the Wak — centipede — dynasty. It’s like the ancient Saxon kings England buried in Old Minster, the original church underneath Winchester Cathedral.”

The tomb, discovered by Guatemalan archaeologists of the U.S.-Guatemalan El Perú-Waka’ Archaeological Project (Proyecto Arqueológico Waka’, or PAW), has been provisionally dated by ceramic analysis to 300-350 A.D., making it the earliest known royal tomb in the northwestern Petén region of Guatemala.

Previous research at the site has revealed six royal tombs and sacrificial offering burials dating to the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries A.D.

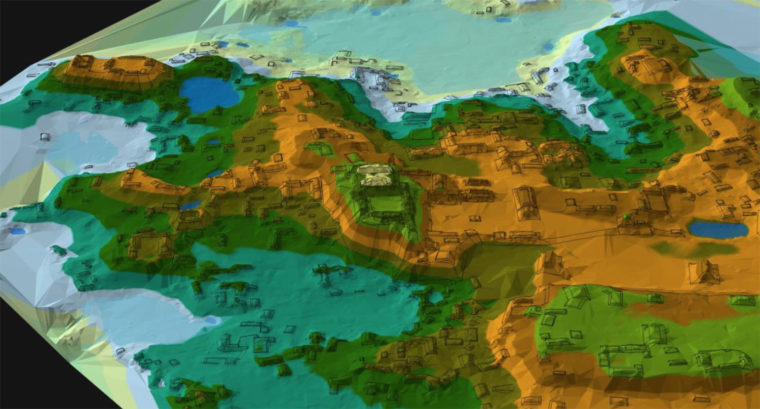

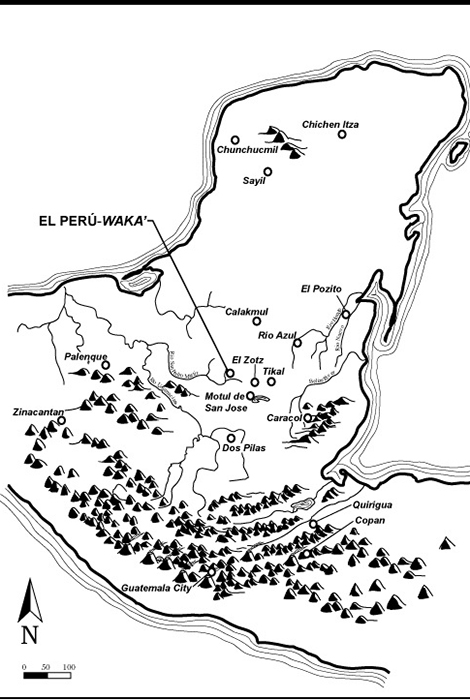

El Perú-Waka’ is about 40 miles west of the famous Maya site of Tikal near the San Pedro Martir River in Laguna del Tigre National Park. In the Classic period, this royal city commanded major trade routes running north to south and east to west.

The findings, first disclosed at a Guatemalan symposium sponsored by the Ministry of Culture, suggest the new tomb, known as “Burial 80,” dates from the early years of the Wak (centipede in Mayan) royal dynasty.

One of the earliest known Maya dynasties, the Wak is thought to have been established in the second century A.D. based on calculations from a later historical text at the site.

Although the ruler in Burial 80, identified as a mature man, was not accompanied by inscribed artifacts and is therefore anonymous, he is possibly King Te’ Chan Ahk, a historically known Wak king who was ruling in the early fourth century A.D., the research team suggests.

Freidel has directed research at this site in collaboration with Guatemalan and foreign archaeologists since 2003.

Anthropologists Juan Carlos Pérez Calderon of San Carlos University in Guatemala and Damien Marken of Bloomsburg University in Pennsylvania are project co-directors. Olivia Navarro-Farr, assistant professor at the College of Wooster in Ohio, is co-principal investigator and long-term supervisor of the site.

Calderon and Guatemalan archaeologists Griselda Pérez Robles and Damaris Menéndez supervised tunnel excavations inside the Palace Acropolis that led to the new tomb.

Identification of the tomb as royal is based on the presence of a jade portrait mask depicting the ruler with the forehead hair tab of the Maize God. Maya kings were regularly portrayed as Maize God impersonators. This forehead tab has a unique “Greek Cross” symbol which means “Yellow” and “Precious” in ancient Mayan. This symbol is also associated with the Maize God.

Robles and Menéndez discovered the mask under the head of the ruler, and it may have been made to cover the face rather than as a chest pectoral. Archaeologists at Tikal in the 1960s discovered a similar greenstone mask in the earliest Maya royal tomb, dating to the first century A.D.

Additional offerings in Burial 80 included 22 ceramic vessels, Spondylus shells, jade ornaments and a shell pendant carved as a crocodile. The remains of the ruler and some ornaments like the portrait mask were painted bright red. Burial 80 was reverentially reentered after 600 A.D. at least once, and it is possible that the bones were painted during this reentry.