Nearly a quarter century ago, a genetic variant known as ApoE4 was identified as a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease — one that increases a person’s chances of developing the neurodegenerative disease by up to 12 times.

However, it was never clear why the ApoE4 variant was so hazardous. When the ApoE4 protein is present, clumps of the protein amyloid beta accumulate in the brain. But such clumps alone do not kill brain cells or lead to characteristic Alzheimer’s symptoms such as memory loss and confusion.

Now, a study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that the presence of ApoE4 exacerbates the brain damage caused by toxic tangles of a different Alzheimer’s-associated protein: tau. In the absence of ApoE, tau tangles did very little harm to brain cells.

The findings suggest that targeting ApoE could help prevent or treat the brain damage present in Alzheimer’s disease, for which there are currently no effective therapies.

“Once tau accumulates, the brain degenerates,” said senior author David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of the Department of Neurology. “What we found was that when ApoE is there, it amplifies the toxic function of tau, which means that if we can reduce ApoE levels we may be able to stop the disease process.”

The study is published Sept. 20 in the journal Nature.

Alzheimer’s, which affects one in 10 people over age 65, is the most common example of a family of diseases called tauopathies. The group also includes chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which plagues professional boxers and football players, and several other neurodegenerative diseases.

To find out what effect ApoE variants have on tauopathies, Holtzman and graduate student Yang Shi and their colleagues turned to genetically modified mice that carry a mutant form of human tau prone to forming toxic tangles.

They utilized mice that lacked their own version of the mouse ApoE gene or replaced it with one of the three variants of the human ApoE gene: ApoE2, ApoE3 or ApoE4. Compared with the majority of people who have the more common ApoE3 variant, people with ApoE4 are at elevated risk of developing Alzheimer’s, and those with ApoE2 are protected from the disease.

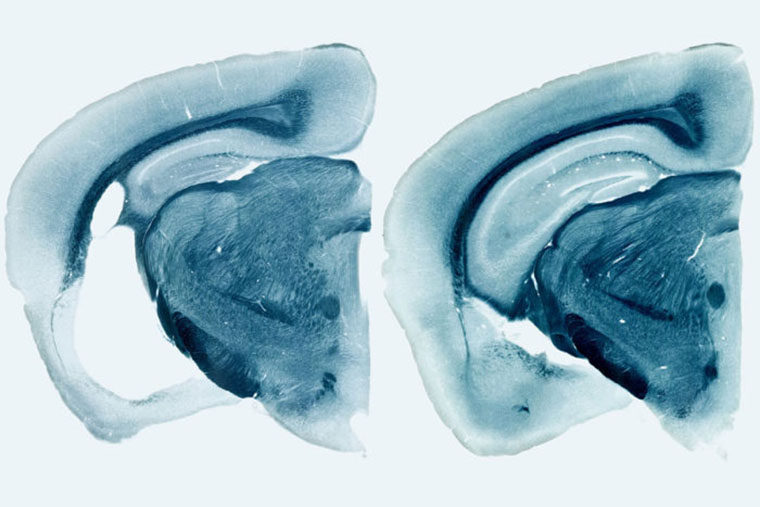

By the time the mice were 9 months old, the ones carrying human ApoE variants had widespread brain damage. The hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, important for memory, were shrunken, and the fluid-filled space of the brain had enlarged where the dead cells had been. ApoE4 mice exhibited the most severe neurodegeneration, and ApoE2 the least. The mice that lacked ApoE entirely showed virtually no brain damage.

Further, the immune cells in the brains of mice with ApoE4 turned on a set of genes related to activation and inflammation much more strongly than those from ApoE3 mice. Immune cells from mice lacking ApoE were barely activated.

“ApoE4 seems to be causing more damage than the other variants because it is instigating a much higher inflammatory response, and it is likely the inflammation that is causing injury,” Holtzman said. “But all forms of ApoE – even ApoE2 – are harmful to some extent when tau is aggregating and accumulating. The best thing seems to be in this setting to have no ApoE at all in the brain.”

To find out whether ApoE in people similarly exacerbates neuronal damage triggered by tau, the researchers collaborated with Bill Seeley, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco. Seeley identified autopsy samples from 79 people who had died from tauopathies other than Alzheimer’s disease in the past 10 years. The researchers examined each brain for signs of injury and noted the deceased’s ApoE variants. They found that, at the time of death, people with ApoE4 had more damage than those that lacked ApoE4.

ApoE transports cholesterol around the body via the bloodstream. A few, rare individuals lack a functional ApoE gene. Such people have very high cholesterol levels and, if untreated, die young of cardiovascular disease. The lack of ApoE in their brains, however, creates no obvious problems.

“There are people walking around who have no ApoE and they’re fine cognitively,” Holtzman said. “It doesn’t appear to be required for normal brain function.”

These findings suggest that decreasing ApoE specifically in the brain could slow or block neurodegeneration, even in people who already have accumulated tau tangles. Most investigational therapies for Alzheimer’s disease have focused on amyloid beta or tau, and none has been successful yet in changing the trajectory of the disease. Targeting ApoE has not yet been tried, according to Holtzman.

“Assuming that our findings are replicated by others, I think that reducing ApoE in the brain in people who are in the earliest stages of disease could prevent further neurodegeneration,” Holtzman said.