When Robin McDowell got burned out by the stresses of her job as a foreign correspondent, she took a year off, and she and her young son explored a rainforest on the island of Borneo, Indonesia. They were blissfully unplugged from the world, with just their boat, some bedtime stories and some orangutans for company.

For many, such an undertaking would be way outside their comfort zone. But then, much of McDowell’s career, including being chased through the Arafura Sea by someone in angry pursuit, seems unnerving.

McDowell was part of a team of investigative journalists that told the story of rampant slave labor in the fishing industry in Southeast Asia, a body of work that earned her numerous awards, crowned by the 2016 Pulitzer Prize.

But her early years were much quieter.

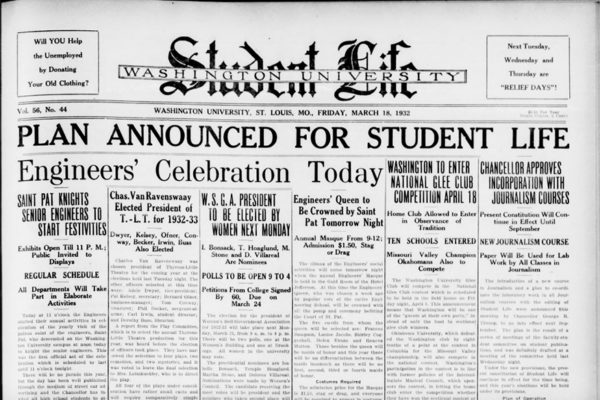

McDowell attended Washington University, graduating in 1988 with a bachelor’s degree in English and American literature in Arts & Sciences. But for her, the campus felt more like home. After all, her father, Robert McDowell, was chairman of the Department of Mathematics for 14 years. (He is now professor emeritus.) And she spent her childhood with faculty members coming over for dinner and the family dog roaming about campus until darkness fell.

“Washington University was my backyard,” she recalls fondly.

She then went to Cambodia to help start a newspaper and train journalists in a country experiencing a free press for the first time in years. In 1996, she joined The Associated Press.

After she finished her degree, McDowell headed to Boston and then New York to work for textbook publishers. She got her start in journalism reporting on national stories for a Japanese newspaper. She then went to Cambodia to help start a newspaper and train journalists in a country experiencing a free press for the first time in years. In 1996, she joined The Associated Press.

More than once, she has found herself in cities where major news events unfolded. She spent a year covering the Columbine High School shooting and its aftermath. A few years later, she was working for the AP in New York when 9/11 happened.

“I heard the explosion from my house in Soho,” she recalls. Nine months pregnant at the time, she hopped on her bicycle and headed to the scene to view the damage, talk to witnesses and report back to the news desk.

After her maternity leave, she returned to Asia, eventually running the AP bureau in Jakarta, Indonesia, covering terror attacks, tsunamis and more. That stretch led to her year off living in a boat traveling through a rainforest.

After years of crazy hours covering conflicts and tragedy, McDowell decided to return to the United States to give her son, Ty, some sense of his roots and his family. In 2005, she bought a house in Minnesota near her sister and planned to step away from journalism.

But then the AP opened a bureau in Myanmar and persuaded her to move again. That assignment led to her work, as part of a team of journalists, documenting the slave labor in the southeast Asian fishing industry, a system that supplies shrimp and other seafood to American and European markets. (For the AP investigative report, click here.)

The team tracked down, interviewed and photographed slaves and runaways from fishing boats. They explained the harsh conditions in which the fishermen worked: sometimes 20-hour shifts, scarce food and water, little medical care, little or no pay, and often spending months at sea.

McDowell and her fellow reporters also followed seafood trucks, used customs documents and studied satellite images to conclusively track a major shipment from the fishing boats to processing plants and then to major seafood suppliers for U.S. restaurants, grocery stores and pet food companies. They hoped to provide a lens through which to tell the story and make Westerners care and, ultimately, to push for changes.

“These stories deserve to be told,” she says.

While it was heartbreaking to hear the fishermen’s stories and then leave them still stranded on ships or in island jails, McDowell said she was confident the situation was temporary.

“There was no question in my mind they were going to be rescued,” she says.

Her team’s investigation ultimately led to about 2,000 slaves being freed and allowed to return home.

She also recounted the “most harrowing experience” of having somebody who was angry over their reporting chase them in a speedboat late at night as they worked to get photos of a fishing boat being unloaded. They presumed it might have been someone tied to the village or factory owners.

Her team’s investigative work garnered a number of journalism honors in 2016, including the George Polk Award for Foreign Reporting; the gold Barlett and Steele Award for Investigative Business Journalism; and the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, the most prestigious of the Pulitzer Prizes. Awards are nice, but McDowell said she was frustrated that companies that buy those products didn’t use their clout to demand more systemic changes in government policy.

“Human trafficking touches almost everything we eat and wear.”

— Robin McDowell

She still eats seafood today, though after her reporting experience, she avoids packages labeled as from Thailand. Yet even activists say that individuals avoiding certain products doesn’t really create change, she says.

“Human trafficking touches almost everything we eat and wear,” she says. “I can’t boycott everything.”

These days, she has hung up her foreign correspondent hat and resumed living in Minnesota, working for the AP as an investigative reporter. Her son, Ty, is 15 and preparing to start his sophomore year of high school.

She maintains that a dogged, independent media is as acutely needed today as in the past.

“At the same time it’s being attacked, people recognize that it’s more important,” McDowell says.

She encourages young journalists who want to tell stories with impact, as she has, to always be chipping away at a side project they care about around the day-to-day assignments, whether they are reporting from Afghanistan, New York or small-town Iowa.

“Focus on the stories that are really the big open secrets,” she says. “If you can make people understand it, be touched by it, those are the ones that are going to resonate the loudest.”

Editor’s note: The Pulitzer Prize-winning series is the subject of an AP book, Fishermen Slaves: Human Trafficking and the Seafood We Eat.