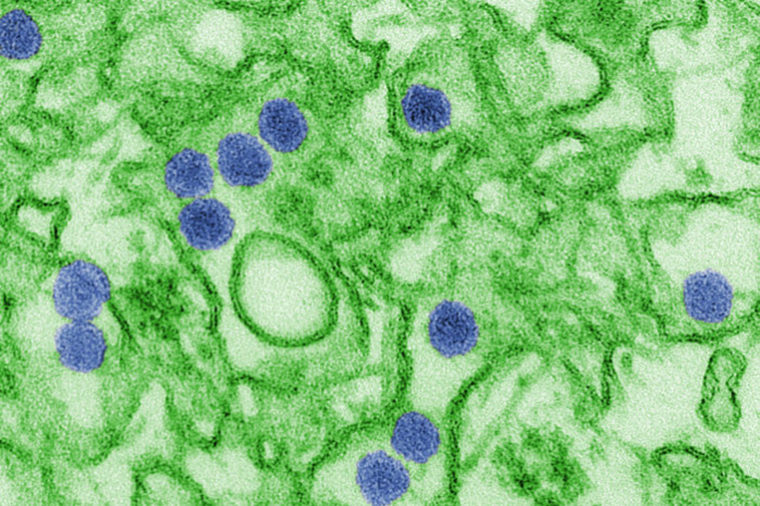

Zika virus causes a mild, flu-like illness in most people, but to pregnant women the dangers are potentially much worse. The virus can reduce fetal growth, cause microcephaly, an abnormally small head associated with brain damage, and even trigger a miscarriage.

Now, a new study in mice shows that females vaccinated before pregnancy and infected with Zika virus while pregnant bear pups who show no trace of the virus. The findings offer the first evidence that an effective vaccine administered prior to pregnancy can protect vulnerable fetuses from Zika infection and resulting injury.

“There are several vaccines in human trials right now, but to date, none of them has been shown to protect during pregnancy,” said Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and the study’s co-senior author. “We tested two different vaccines, and they both provided substantial protection.”

The study is published July 13 in the journal Cell.

Zika made international headlines when it was linked to an epidemic of babies born with microcephaly in Brazil. There is no specific medicine or vaccine to prevent or treat disease caused by the mosquito-borne virus.

Last year, Diamond and others developed a mouse model of Zika infection that mimics the effects of the infection in pregnant women. Using this model, Diamond, along with co-senior authors Pei-Yong Shi, of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), and Ted Pierson, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), evaluated the ability of two vaccines to protect fetuses whose mothers were infected during pregnancy.

One, a so-called subunit vaccine that is based on the genetic blueprint for two proteins from the virus’ outer shell and is developed by Moderna Therapeutics, is already in safety testing in women who are not pregnant and men. The other, a live but weakened form of the virus that was developed at UTMB, is being tested in animals.

As part of the study, groups of 18 to 20 female mice were vaccinated with one of the vaccines or a placebo, and some animals received a second dose of the same vaccine or placebo a month later. Three weeks later, the researchers measured antibody levels in the mice’s blood as a measure of the strength of their immune response. They found that both vaccines had elicited very high levels of neutralizing antibodies against Zika, while the placebos had not.

After the mice became pregnant, they were infected on the sixth day of pregnancy, to mimic the experience of a woman bitten by a Zika-carrying mosquito early in pregnancy.

One week after infection, the researchers measured the amount of virus in the mothers and fetuses.

With both vaccines, fetuses and placentas from vaccinated mice contained very low levels of Zika’s genetic material. For the subunit vaccine, more than half of the placentas and fetuses had no detectable viral genetic material at all. The live-virus vaccine was even more effective: In 78 percent of the placentas and 83 percent of the fetuses no viral genetic material was found.

“The amount of viral genetic material in the placentas and fetuses from the vaccinated females was just above the limit of detection,” said Diamond, who also is a professor of molecular microbiology, and of pathology and immunology. “It’s not totally clear whether it was infectious virus or just remnants of viruses that had already been killed.”

In contrast, the amount of detectable viral material in the placentas and fetuses of unvaccinated mice was hundreds to thousands of times higher.

The researchers repeated the experiment with different mice so they could evaluate the pups at birth. None of the mothers in the placebo group made it to term. The mothers became seriously ill, many of the fetuses showed high levels of infection and died in utero, and the placentas showed severe damage. In contrast, the vaccinated mothers remained healthy, all of their pups were born without obvious signs of injury, and the newborn pups had no measurable Zika virus in their heads.

“In general, most doctors don’t want to vaccinate during pregnancy on the outside chance that the immune response itself could harm the fetus,” Diamond said. “But if you’re in an area where Zika is circulating, you might vaccinate during pregnancy because the risk of Zika infection is worse than some theoretical risk of immune-mediated damage.”

The study did not look at whether the vaccines are safe and effective for use during pregnancy. Such studies couldn’t really be done in mice, Diamond explained, because mouse pregnancies only last 19 days. That doesn’t allow enough time for a protective immune response to develop before the pups are born.

This study also does not address the question of whether the vaccines work when pregnant women are infected with Zika through sexual contact. It is possible that Zika virus in semen can travel to the uterus and then to the fetus without passing through the bloodstream.

“The question is, ‘Would the immunity still hold up if the virus does not pass through the bloodstream?’” Diamond said. “We think it will hold up, but that has to be tested.”