Copper has long been known for its ability to kill bacteria and other microbes.

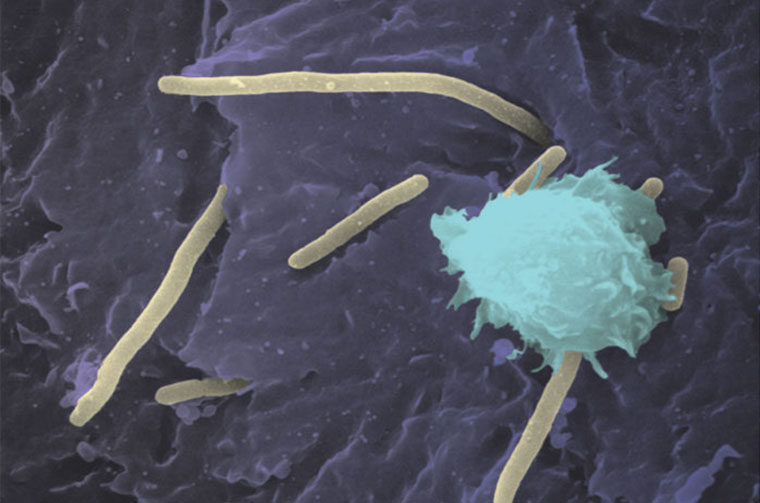

But in an interesting twist, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown that Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria — those at the root of hard-to-treat urinary tract infections (UTIs) — hijack trace amounts of copper in the body and use it as a nutrient to fuel growth. The finding suggests blocking this system may starve E. coli infections, opening the door to treating UTIs using drugs that work differently from traditional antibiotics.

The study is published July 24 in Nature Chemical Biology.

Copper is an essential mineral — found in shellfish, whole grains, nuts, beans and other foods. It can kill pathogens in high concentrations. But it was unclear how E. coli handles copper ions present in urine, an extremely complex medium containing many trace metals and other compounds.

In past work studying strains of E. coli known to cause difficult-to-treat UTIs, the researchers showed that a molecule called yersiniabactin that is secreted by the bacteria sequesters copper, preventing it from accumulating to antibacterial levels. But what it does with this bound copper has been unknown.

“Yersiniabactin is more common in invasive bacteria, including E. coli,that cause the more problematic recurring and antibiotic-resistant urinary tract infections,” said senior author Jeffrey P. Henderson, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine. “One of the reasons we treat UTIs is out of concern that the bacteria will invade other areas and go from being a nuisance to a much more serious infection. Because yersiniabactin seems to be associated with more virulent bacteria, we wanted to understand what it’s doing and why it’s there.”

While bacteria are known to bring iron — another essential mineral — into the cell, the researchers noted that E. coli have long been thought to lack a method to import copper. Indeed, scientists have assumed that yersiniabactin only imports iron.

In the new study, the researchers showed that yersiniabactin imports copper ions into the cell, where these charged particles help trigger the many biochemical reactions that bacteria require to grow and reproduce. The scientists further showed that once relieved of its mineral cargo, yersiniabactin goes back outside the cell to mop up more copper. The researchers dubbed this strategy “nutritional passivation.” In metallurgy, passivation refers to treating or coating metal to make it less reactive.

The researchers also have shown that yersiniabactin can bind to a variety of metals beyond copper and iron, including nickel, cobalt and chromium.

“The traditional idea that yersiniabactin is an iron importer is far too simplistic a view of this molecule,” said Henderson, who treats patients with UTIs. “Bacteria that secrete yersiniabactin can bind to all sorts of metals. At the site of infection, this molecule appears to be grabbing onto metals all around it, preventing these metals from reaching toxic levels, but also bringing in controlled amounts of metal ions for nutritional purposes.”

Henderson and his colleagues noted that strains of E. coli without the ability to bring copper-bound yersiniabactin into the cell were less aggressive than strains that could import copper via this route. The researchers said future work in antibacterial drug development could seek ways to block yersiniabactin, essentially starving the cell of essential nutrients.

This strategy may be relevant beyond the E. coli that cause recurrent UTIs, according to the researchers. Henderson noted that the yersiniabactin molecule is present in bacteria that cause plague and in bacteria that commonly cause pneumonia.