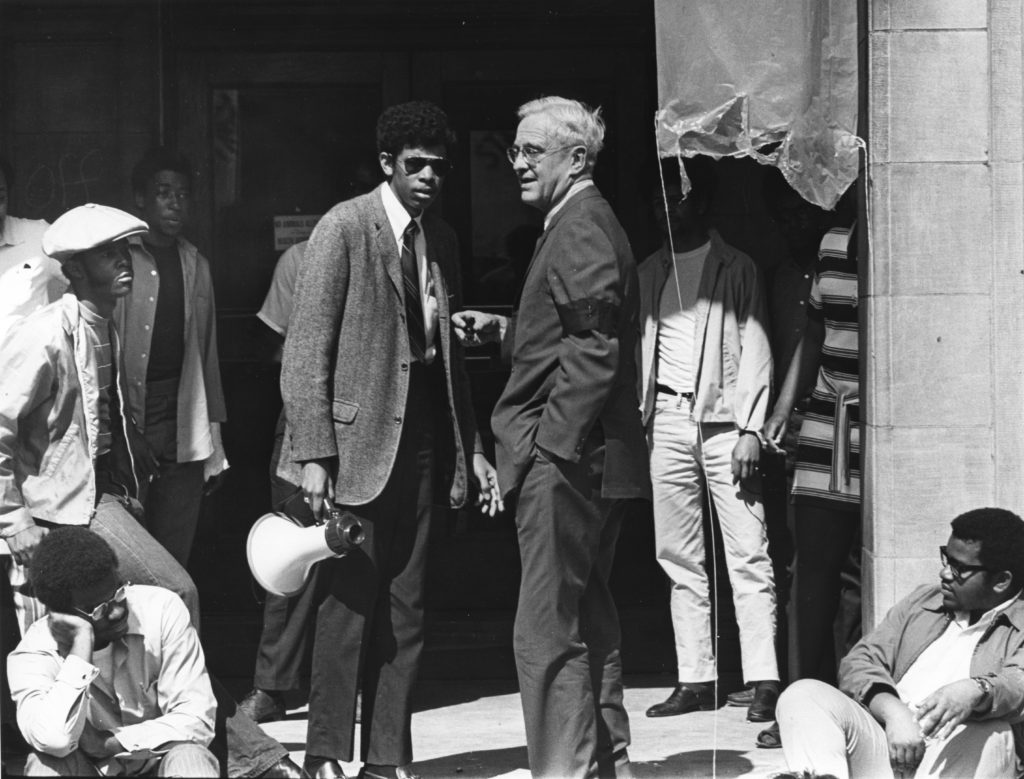

It started with an act of protest.

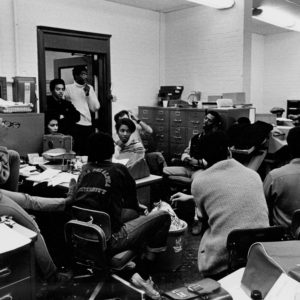

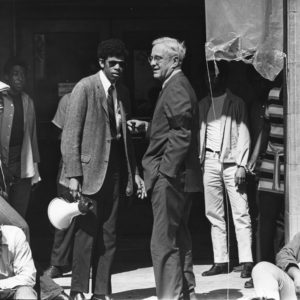

In the fall of 1968, as political turbulence rocked the nation, dozens of members of the Association of Black Students at Washington University in St. Louis confronted administrators in the corridors of Brookings Hall. Chief among their demands was the call to establish a black studies program, which students argued would “radically reform our future education.”

Founded the following the year, the university’s African and African-American Studies (AFAS) program, as it is known today, grew to include more than 30 core and affiliated faculty. This spring, the university will mark a new chapter when AFAS becomes a full department within Arts & Sciences.

“This has long been a dream for all of us connected with African and African-American Studies,” said Gerald Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters. “Certainly, when I came to campus in 1982, people aspired to see the program become a full department. They felt it was not just an academic goal but also a kind of political goal. They hoped it would bring more presence and prestige to the study of African-descended peoples.

“There are still challenges, but this is an important moment,” added Early, a former AFAS director who will be the inaugural chair and oversee the transition of the program into a department. “A person doing, let’s say, black literature within black studies is going to be oriented somewhat differently — in ways both subtle and important — from a person doing black literature within English.

“We felt that we needed to become a department in order to live up to our promise and ideals.”

Interdisciplinary scholarship

Early noted that, unlike most traditional departments, AFAS is dedicated to issues and questions that are fundamentally interdisciplinary in nature. Faculty and students draw on insights and scholarship from across the humanities and social sciences as well as from law, medicine, social work and other areas.

“Sometimes, it’s not easy to get those pieces to work well together,” Early explained. Within traditional disciplines, “faculty may have different methods or may specialize in different things, but they’re all starting on the same page. Getting people to think more broadly about the mission of an interdisciplinary program can take skill and diplomacy.”

But in recent years, the rise of intersectional theory and other forces have led a generation of academics to embrace methods and approaches that black studies programs have historically pioneered.

“Today, if you aren’t mixing two or three disciplines, you’re old-fashioned,” Early quipped. “Many scholars, especially young scholars, feel constrained by traditional departments. Students also tend to find these programs interesting and engaging because they look at things, and value things, a little differently. They want to reshape the questions that are being asked.”

As a full department, AFAS will be better positioned to set curriculum and drive hiring decisions. But perhaps most importantly, Early said, “we can diversify the types of scholarship being done.”

“I’m thrilled that the university has taken this step,” said Barbara A. Schaal, dean of the faculty of Arts & Sciences. “It’s something that will greatly enhance the scholarly study of race and ethnicity on our campus as well as the educational opportunities of our students. As in the case of sociology and, more recently, women, gender and sexuality studies, this change in status for AFAS reflects the increasing importance of our Arts & Sciences disciplines in addressing national and global issues.

“I am deeply grateful to Gerald Early for his leadership of AFAS throughout the years,” Schaal added, “and for his exceptional vision and commitment in leading the effort to make AFAS a department.“

Ideas and opportunity

The transition from program to department comes amidst larger university efforts to foster a more inclusive environment. Since 2011, the number of first-year undergraduates eligible for Pell Grants has nearly doubled, while the Danforth Campus increased by 63 percent the number of tenured and tenure-track African-American faculty.

“The purposes of higher education are to create original knowledge and provide opportunity to our students,” said Provost Holden Thorp. “We are committed to generating new knowledge, new frameworks, and new ways of understanding the world. We are compelled to replace conflict with empathy and understanding. Recognizing AFAS as a full department helps to fulfill all of these goals. It is the right thing to do, and I am deeply grateful to all the students and faculty who have worked to bring this change about.”

As Early pointed out, departmental status helps to alleviate a longstanding sense of precariousness and even embattlement within the black studies community: “People felt they were constantly having to explain why the program is important.” It also boosts morale, aids future recruiting and creates new opportunities for leadership positions. (Indeed, a search for Early’s successor as chair is underway.)

“As an alum of the AFAS program and the daughter of one of its late adjunct professors, I’ve long known the brilliance and importance of our program,” said Brittany Packnett (AB ’06), a vice president with Teach for America who served on the Ferguson Commission and the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. “I’m thankful that the university has arrived at this point — and hope that the resources, support and attention AFAS deserves will be increased given this important decision. The AFAS program has produced important thought leadership, activism and scholarship. I’m excited about what lies ahead and thankful to the faculty who have enriched it thus far.”

“Campus is becoming a more diverse place, and I think there’s a greater awareness that we’re an urban university,” Early added. “Even before Ferguson, I think students were getting stronger signals that they should meaningfully interact with St. Louis and understand the nature of the city around us — though Ferguson may have underscored that point.

“Today, if you want to be a first-class university, you have to cultivate a diversity of interests, experiences and approaches as well as a diversity of faculty and students.”