Nightmares, mood swings, an aversion to crowds, a fear of loud noises.

Today, we recognize these symptoms as signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). But in 2004, PTSD had yet to insinuate itself in the American vernacular. The military didn’t understand it; the medical profession didn’t understand it. And James Petersen, a Marine who served at Iraq’s infamous Abu Ghraib prison, certainly didn’t understand it.

“I was angry all of the time and I didn’t know why,” said Petersen, now a master’s degree student in the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis and president of WUVets, a student group for veterans. “I got in stupid fights with my parents; I hated the fireworks at Fair St. Louis. The worst was trash day. There was this dumpster outside my window and whenever the trash truck put it down, it sounded like a 120-millimeter enemy mortar.”

Originally from Collinsville, Ill., Petersen joined the Marine Corps infantry in 1999. He spent several years stateside before he was deployed to Fallujah in Iraq. He loved the work; he loved the Iraqi people.

“At the time, most of the people were happy we were there,” Petersen said. “We handed out school supplies and candy, and helped build a school. Still, it was an incredibly dangerous place. Whenever you would leave the base, there were IEDs (improvised explosive devices) waiting for you.”

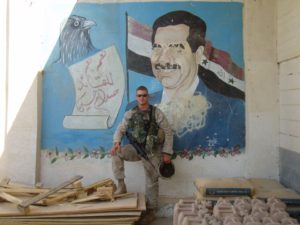

Then Abu Ghraib happened. Petersen’s unit was dispatched to protect the prison after the media exposed the abuse of Iraqi prisoners by American soldiers. The scandal was just the latest episode in the prison’s dark history. Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had killed thousands of his own citizens in the prison’s torture chambers.

“The wild dogs would dig up bones from the mass graves and bring them to you,” Petersen said. “The place was just steeped in evil. And it was attacked every single day — car bombs, rockets, mortars, rocket-propelled grenades. The whole site was about the size of the Brown School campus, so when it got attacked, you felt it.”

After seven months, Petersen’s unit returned stateside. He got his undergraduate degree; he got married. But he struggled.

“I was surprised by how hard it was to be home,” Petersen recalled. “I missed the sense of community. I missed having a very clear purpose. Life seemed so much easier in Iraq; either you lived or you died.”

Instead of getting help, Petersen went back. He served five years as a private contractor in Iraq and then Afghanistan. He survived more attacks; witnessed more death. And when he got home, he experienced more nightmares. This time, at his wife’s urging, Petersen sought treatment for his PTSD from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Slowly but surely, weekly therapy made a difference.

“I was taught to reframe what I was thinking and how I was feeling,” Petersen said. “I remember thinking, ‘Yes I’m at Costco on Saturday, and yes, it is crowded, but no one here is wearing a suicide vest.’ I was very surprised how well it worked.”

In the meantime, Petersen had taken a job at St. Patrick Center finding homeless veterans on roadways and intersections and connecting them to services.

“The only difference between me and them was luck, my family and the therapy,” Petersen said. “I realized I wanted to help veterans with PTSD the way I had been helped. But to do that, I needed to get my master of social work.”

Washington University provided him an opportunity and a scholarship. At the Brown School, Petersen has studied mental health and has continued to work with homeless veterans through his practicum at Missouri Veterans Endeavor.

He currently is collaborating with Danielle Bristow, assistant dean for academic affairs at the Brown School; Ashley Macrander, assistant dean for graduate student affairs at The Graduate School; and fellow master of social work student Jennifer Goetz to bring “Veteran Ally” training to faculty and staff. The program will provide employees a better understanding of the issues veterans face in college.

“James has been an incredible advocate for his community,” Bristow said. “Instead of saying, ‘Here is my issue. What are you going to do about it?’ He says, ‘Here are some solutions. How can we work together to make things better?’

“He is a visionary.”

That same drive is motivating Petersen to stage the biggest Veterans Day event in recent university history. The event, scheduled for 6 p.m. Friday, Nov. 11, in the Bryan Cave Moot Courtroom, brings together a diverse panel of combat veterans to share their experiences and invited federal, state and local leaders to speak about veterans issues.

Petersen even contacted dozens of celebrities associated with veterans causes and asked them to attend the event. No one took him up on the invite, though St. Louis’ own Ellie Kemper offered to send a video greeting.

“You have to try,” Petersen said.

Speakers include David Birge, who served World War II as a Marine; Donald Graveman, who served in World War II and Korea as an Army officer; Jack Zerr, who served in Vietnam as a fighter pilot and Navy admiral; George Grimm, who served in Afghanistan as a Marine sergeant; and David Spurling, who served in Afghanistan as a staff sergeant.

Also on the panel are Marine veterans Rudy Reyes and Josh Person, whose lives were chronicled in “Generation Kill,” the award-winning book and HBO miniseries.

U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., will be the keynote speaker. Other speakers include St. Louis County Circuit Court Judge Judy Draper and Missouri state Sen. Jill Schupp, who will discuss the Missouri Veterans History Project, a nonprofit she founded to record and share the personal stories of the state’s veterans.

“James has worked hard to raise the profile of Veterans Day on campus,” Provost Holden Thorp said. “This panel presents a rare opportunity for our community to hear from so many voices who are so deserving of our support and engagement. Washington University is very proud of all of the work we are doing to enhance the experience of veterans in our community.”

It’s an important message at a school where only a small percentage of students have fought on a battlefield. Petersen understands why his classmates choose school over service. But, given the opportunity, he would make the same choice again.

“Academically, emotionally — I am who I am because of those years,” Petersen said. “When you’ve gone through what I’ve gone through, you know what’s important.”