Why is the relationship between religion and politics so fraught here, in this country that prides itself on dividing church and state? When does religious freedom grant us the right to discriminate? What role is Christianity playing in the 2016 presidential election? Is the growing minority of Americans who claim not to be religiously affiliated making the country more divided or less? Just how polarized are we as a nation? Is any consensus emerging?

Six years ago, when the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics was founded, its mission seemed almost impossible: “To serve as an open venue, fostering rigorous scholarship and informing broad academic and public communities about the intersections of religion and U.S. politics” — two of the controversial topics we’ve all been taught to avoid in polite conversation.

Today, public conversations about religion and politics are plentiful and seldom remain polite. We’re living through a fractured, angry period in which political rhetoric and public opinion are equally prone to vehemence, extremism and rigidity. So the center’s mission has become perhaps even more imperative, serving as a place that encourages dialogue between diverse and even conflicting points of view.

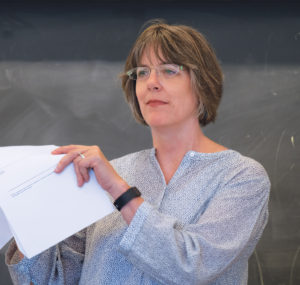

(James Byard/WUSTL Photos)

Backgrounding an election year

“It’s been a surprising year,” R. Marie Griffith says dryly. As the John C. Danforth Distinguished Professor in the Humanities and director of the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, it’s Griffith’s job to remain coolly nonpartisan. That’s second nature to her when it comes to the tangle of religious freedom and sexuality issues clogging the courts; her areas of expertise include evangelical Protestantism and gender in 20th-century America. But when reporters call to ask why Donald Trump is slamming Pope Francis or calling himself Christianity’s politically incorrect protector, Griffith and her colleagues work hard to decipher the role religion is assuming in the current political landscape.

In an election year that’s breaking precedent left and right, center faculty have been called on to analyze issues of immigration, gender and sexuality, religious freedom, racial justice (or injustice), attitudes toward Muslim Americans, and the platforms and behavior of presidential candidates eager to appeal to religious voters in ways that were sometimes formulaic, sometimes wildly unpredictable.

Since spring 2012, the center has published an online journal, Religion & Politics, that shares recent scholarship (from the center and around the world) about these fraught topics. And with the university scheduled to host a presidential debate Oct. 9, 2016, the center hopes to raise its profile and influence.

On Oct. 8, the day before the debate, Krista Tippett — host of the Peabody Award–winning public radio conversation and podcast, On Being — will moderate a new experiment at the center called the Danforth Dialogues: intense discussions between public intellectuals about how religion and politics might intersect in the future. Between the debate and the election, Jon Meacham, former Newsweek editor, contributing editor to Time and Pulitzer Prize winner, who gave the center’s inaugural address six years ago, is scheduled to speak. His anticipated talk is titled “Faith and Power: Religion and the American Presidency From the Founding to Trump v. Clinton.”

“Looking ahead, we want to become more involved in Washington, D.C.,” Griffith explains, “to connect the conversations we are having here — the knowledge we are creating — more directly to policymakers and others who set the national agenda.”

Expertise runs deep and wide

Five years ago, when Griffith became the center’s director, she and Leigh Eric Schmidt — an acclaimed historian of religion who happens to be Griffith’s husband — were the only faculty.

Schmidt, the Edward C. Mallinckrodt Distinguished University Professor in the Humanities, is a prolific scholar. His work has examined topics from mysticism to the New Atheism, and it includes a religious history of American neuroscience and a book about the commercialization of holidays in the U.S.

Griffith, by contrast, takes a contemporary, anthropological tack. Diving into issues ranging from women’s roles in American evangelicalism to the regulation of the body’s appetites in Christianity, she has written about religious conceptions of gender, sexuality and contraception, as well as fasting, dieting and abstinence.

Husband and wife disagree regularly and cheerfully, and they’ve sorted out the power issues: “When we were at Princeton, he was the department chair,” Griffith says. “At Harvard, we both held chaired professorships. Then we came here, and I’m the director. We can manage any dynamic!”

Today, Griffith and Schmidt have four colleagues at the center whose curricula vitae are dotted with impressive doctoral, divinity and law degrees, and whose fields include the history, diversity, changing landscape and unique role of religion in American public life.

Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp, the Archer Alexander Distinguished Professor, is a past president of the American Society of Church History and the Mormon History Association. Her academic interests move fluidly among African-American religions, Mormonism (she’ll soon publish a survey of Mormonism in American life), religion on the Pacific borderlands of the Americas and issues of intercultural contact. Grounded in 19th-century religious expression in the United States, she’s ranged freely across its many forms, writing about sacred texts, race histories, Chinese immigrants, Protestant practice and women’s work.

Mark Valeri, the Reverend Priscilla Wood Neaves Distinguished Professor of Religion and Politics, studies the interweaving of religion, social thought and economics. He wrote an acclaimed study of the shift from a Puritan disregard for personal profit to a celebration of it. And though he is deeply informed about the country’s foundational ideas, he has no problems transitioning to the present: He co-edited Global Neighbors: Christian Faith and Moral Obligation in Today’s Economy.

Armed with a master’s degree in divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary and a doctorate in religious history and culture from Emory University, Lerone A. Martin arrived as a postdoctoral fellow and is now assistant professor of religion and politics. Martin was a research consultant for continuing education and recidivism at New York’s Sing Sing State Prison. He currently chairs the American Academy of Religion Committee on Teaching and Learning.

John Inazu was recently named the inaugural Sally D. Danforth Distinguished Professor of Law and Religion, a joint appointment in the center and the law school. Inazu’s scholarship focuses on the First Amendment freedoms of speech, assembly and religion. His most recent book, Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving Through Deep Difference, argues that we must pursue a common existence in spite of our deeply held differences. (See sidebar above for more on Confident Pluralism.)

The Danforth Center on Religion and Politics also includes two visiting scholars and several affiliated faculty members with appointments in other departments but a strong academic interest in American religion. The strength of this faculty has made robust course offerings possible. (See sidebar above for a description of Abram Van Engen’s course “City on a Hill.”) The center also has a strong postdoctoral fellowship program and a public lecture series so lively it often fills Graham Chapel.

Lectures can be uber-specific — one described Christian drug rehabilitation programs in Guatemala — or as broad as religion scholar Stephen Prothero’s sweeping analysis of America’s five culture wars. But they never shy away from controversy and regularly pull in audiences beyond the university community.

Church and state

When Jack Danforth says the intersection of religion and politics has long been an interest of his, it’s an understatement. The former U.S. senator and ambassador to the United Nations is also an ordained Episcopal priest, and his first book was titled Faith and Politics: How the “Moral Values” Debate Divides America and How to Move Forward Together. His second, The Relevance of Religion, looks at the way religious values — sacrifice, selflessness, commitment to the greater good — could be used to close that divide, healing the fractured, angry state that is U.S. politics today.

The center was born in a long and animated conversation between Danforth and Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton. Soon after, Wrighton made a proposal, the Danforth Foundation responded with a $30 million grant, and the university gave the center Danforth’s name and hoped for his continued involvement. He’s given it gladly, even teaming up with his former colleague in the Senate, Joe Lieberman, to give a talk about the lost art of compromise and the escalation of partisanship.

Danforth’s interest in this tense juncture of ideas is “more than idiosyncratic,” he says. “All you have to do is pick up the paper, and most days you’ll find something on religion and politics — and it tends to be something that’s both of consequence and controversial.”

“The great mission of America is to hold together as one people a diverse country. Religion can be very divisive; it’s often used as a sword. Yet at the same time, the meaning of the word is ‘to bind together.’”

— John C. Danforth

So is there something unusual about the way religion and politics intersect in America? “DeTocqueville thought so, and I do too,” Danforth says. “We tend to be more religious than many other parts of the world, but we are also more heterogeneous. The great mission of America is to hold together as one people a diverse country. Religion can be very divisive; it’s often used as a sword. Yet at the same time, the meaning of the word is ‘to bind together.’”

Maffly-Kipp thinks it’s hard even to know how polarized individual Americans really are. As a historian, she’s well aware of other times when xenophobia and even violence tainted religious issues. With today’s social media and 24/7 news cycle, though, “conflict is thrown in our faces a lot more than it used to be,” she says. “Signs of commonality don’t make the news.”

“The TV media need ratings,” Griffith adds, “and the ratings go up when there is conflict, and that has a polarizing effect.” The cure, she’s convinced, is personal interaction — getting out from behind electronic screens and talking to people. “That’s why religious congregations and universities are great spaces for coming together from extremely different backgrounds,” Griffith says. “More and more, people consume only the news media that match their beliefs, which leads to isolation. If we are to hold together as a nation, we must move beyond that.”

In the future, the center plans to hold more dialogues, bringing in people who will vigorously debate the issues without anger or insult. Single lecturers often wind up preaching to a choir: “When we had [conservative columnist] George Will, we had a very conservative audience. Then we had [attorney and women’s rights activist] Sandra Fluke, and we got a completely different audience,” Griffith says. “Even at our events, the polarization of our nation has been visible.”

The more viewpoints brought to a single event, though, the more chance for tension. “When you reach those points, you really find out what people care about — and what they have been taught not to talk about,” Maffly-Kipp explains. “One reason the center exists, though, is to model respectful discourse that doesn’t just lapse into argument.”

Valeri thinks that one way to foster respectful debate is to encourage people to ponder the moral or philosophical issues behind policy or legal disagreements. “Help them articulate the sources of their judgments and listen to the perspectives of others,” Valeri says. “Prompt them to ponder the deep historical backgrounds, which can make our positions, so often cherished with zeal, appear less absolutely necessary.”

We should clearly delineate between heartfelt belief and informed opinion, Danforth says. “If you invest political ideas with religious commitment, then your thinking becomes ‘my way or the highway,’ because then your way is God’s way.”

Heat and light

Asked if there’s any consensus emerging on religious issues in the political arena, Schmidt replies: “How can you create a collegial conversation out of rancorous debate? That’s what we are trying to do at the center. But consensus is so remote on so many issues that I’d have to say it is all but out of reach.”

Griffith, however, sees a “remarkable consensus around same-sex marriage, something no one would have expected.” And she pays attention to such topics: Her books include God’s Daughters: Evangelical Women and the Power of Submission; Born Again Bodies: Flesh and Spirit in American Christianity; and the forthcoming Moral Combat: How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics (fall 2017), in which Griffith analyzes the gender and sexuality debates of the past century and explains why these issues have played such a powerful and divisive role in American Christianity.

Regarding the issue of abortion, however, Griffith says, “That’s as divisive as ever.” And she expects it will remain that way for some time, as will issues of racial justice. “The events in Ferguson resonated with all of us,” Griffith says. “It’s been amazing to see that many of the people involved in trying to heal the wounds exposed by those events have been clergy.”

The Danforth Center on Religion and Politics hosted a gathering in fall 2014, inviting religious leaders from various communities. Maffly-Kipp remembers sitting in the audience, listening and thinking: “This is exactly the kind of conversation we should be encouraging. We were dealing with something very immediate and very fraught, and we needed to allow people to discover their commonalities and talk about their differences in reasonable ways.”

“Religious leaders and communities must speak out more on these issues. Obviously, murder of any kind should be a concern to religious people, so the matter of guns and violence in our time must be addressed.”

— R. Marie Griffith

Maffly-Kipp says that another issue to watch is economics and inequality. And to Griffith, what looms largest is “our problem with guns. The unwillingness of many to accept even the smallest safeguards is hugely problematic, and people are dying at alarming rates,” she says. “Religious leaders and communities must speak out more on these issues. Obviously, murder of any kind should be a concern to religious people, so the matter of guns and violence in our time must be addressed.”

Martin adds questions on Islam and on the appropriate balance between security and privacy to the watch list. “I’ve been doing some historical work on the FBI,” he says, “and I think religion and domestic security will continue to loom large.”

Valeri cites foreign affairs: “intervention in Syria or not, advocacy for persecuted religious minorities overseas, domestic security. On what notions of American national identity, purpose and mandate ought we to address such questions?”

Asked for the hottest issue of the moment, the center’s faculty reach their own consensus: religious freedom — how it’s defined, how it intersects with notions of equality and equal treatment, and what its boundaries are and how they can be negotiated.

This semester, Valeri is team-teaching a course with Inazu. The two are exploring “what religious freedom meant in popular culture, what it meant in law and the courts, and how meanings changed over time,” Valeri says, to frame the current situation, in which “religious freedom issues often focus on the freedom from government’s interference in religious practice.”

In a 2016 media interview, Schmidt pointed out that at the country’s founding, “religious liberty” meant protecting citizens from “the tyrannies and coercions of religious establishments.” Today, the principle is invoked in arguments about employee health insurance. Would a devout Jehovah’s Witness be allowed to refuse his employees coverage for blood transfusions? In that case, Schmidt maintains, religious liberty would grant the freedom to refuse the transfusion for oneself, not the freedom to use employee benefits to urge the same decision on others.

“Religious freedom always needs to be defined,” Schmidt says, “because it’s continually being negotiated.” Some people think the category has become so muddled that we’d be better served talking about other principles, like fairness or equality, but Schmidt thinks it’s too important an idea to set aside altogether.

“The religious freedom ideal is now being used to say that a baker or florist should have a religious right not to serve a gay couple, so liberals are becoming more skittish about the principle in general,” he says. “But religious freedom is a very important American value and has been for a long time. What we have to work on are the ways in which the ideal fails and address those concerns.”

Nowhere else would the question be this fraught, he adds. In England, where there’s still an established church, “they wouldn’t spend as much time puzzling over all this. Here, we are preoccupied with disentangling the two realms — with sorting out and monitoring that boundary.”

Griffith says the paradoxes — and ironies — abound, because while America has a long history of church–state separation, many people also say that America is one of the most religious nations on Earth. According to Griffith, “Religion has affected every aspect of our law. We are a nation that separates religion from politics in a very different way, yet at the same time, our law feels far more religiously influenced than it is in a lot of European countries.”

So is our emphasis on church–state separation mere hypocrisy?

“No, I don’t think it is,” Griffith says. “I think it’s very difficult to draw boundaries around religion. Catholics who deeply believe that abortion is the taking of a precious life are not going to see this as just a religious issue. They are going to see it as murder and, therefore, a matter of law. It’s just truly difficult to separate religion from politics.”

There was a time when people assumed that without a state church, a country would lose all morality, Maffly-Kipp observes. In fact, it was just the opposite. “A certain zest for religious expression exists here,” she says. “Now, how that plays into politics is an ongoing question. It’s always been a question, because there are no models for us.”

How do we negotiate the relationship between the deeply held religious beliefs, which are plural and diverse, and the need for a united government? “As the nation becomes more diverse, we’re facing the true test,” Maffly-Kipp continues.

And then there were ‘nones’

Despite (or maybe because of) all the entanglements of American religion into civic life, more and more people are checking “none” on the “religious affiliation” box.

Valeri wonders: “Are they disengaged from all forms of religion or merely from traditional institutions? Can they be ‘spiritual but not religious’ in meaningful ways?” And is the loss of deep religious, spiritual or metaphysical thinking one reason we’ve grown shallow and so polarized in our discussions?

Granted, “some of those ‘nones’ are reading the Bible or other spiritual literature as well as praying and meditating,” Martin says. “Some are practicing forms of spirituality through the marketplace by, for example, purchasing the products of televangelists or buying Oprah’s chai tea at Starbucks and her self-help magazine as a way to meditate and pursue spiritual enlightenment.”

Isn’t a fusion of capitalism with spirituality a little paradoxical? “Both possibilities and limits exist,” acknowledges Martin, who wrote Preaching on Wax: The Phonograph and the Making of Modern African American Religion to explore the selling of recorded sermons in the 1920s. The possibilities, he points out, are that people can engage in the spiritual practice of their choice. Instead of stratified and sometimes combative religious sects, many people find community with others in simply being spiritual. “One limit,” he concedes, “is that it does allow for capitalism to have a significant influence upon the kinds of spiritual messages we hear.”

Center faculty have had lively discussions about the meaning of the secular, Valeri says. “Is it a way of coming to public opinion — and, therefore, might include religious perspectives — or is it a denial of the value of religion in the public?”

This is Schmidt’s forte. He has long been fascinated by the religion and secularism debates. One of his earlier books was Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality, and it surveyed the colorful, sometimes eccentric search for enlightenment in America. Just last year, he and Valeri taught a class that asked what difference it would make if you imagined the U.S. a Christian nation versus a secular republic. And this fall, Schmidt’s highly anticipated new book is being released: Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation.

“There has been a modest improvement over time in the way Americans think about atheists,” Schmidt says, “if you take a very long view and start in the 17th century, where it was blasphemous and potentially a capital offense. However, even though legal neutrality now exists, most Americans, when they are polled, are still quite suspicious of atheists and agnostics.”

Yet, surely that’s changing, with all these “nones” tilting the scale toward secularism?

Schmidt points out that though “nones” are a growing minority, they still make up only 20 to 25 percent of the population, which leaves a majority of people who feel strongly about religion. “Also, they become mutually reinforcing,” Schmidt adds. “The more the religious folks, often evangelical Christians, are anxious about growing disaffection, the more intensely they try to combat that.” Conversely, he continues, the more the “nones” think religion is oppressive, the more they flee it.

“A lot of younger people are just not convinced they need organized religion, particularly after decades of growing intolerance among religious groups.”

— Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp

Maffly-Kipp has seen this play out time and again: “A lot of younger people are just not convinced they need organized religion, particularly after decades of growing intolerance among religious groups.”

However, she points out that with immigration — especially people coming from parts of the world where there are very devout believers — it’s unlikely that the country as a whole is becoming less religious. There just may be increasing divisions between people who are religious and those who aren’t, making dialogue more important than ever.

Chancellor Wrighton states that these issues make the mission of the center more important than ever as well. “Times like these,” Wrighton says, “when it feels as if there’s a lot of polarization, can also open opportunities for new conversations — ones that move us all forward, and in ways that allow us to live together, perhaps not in agreement, but in understanding.”

— Jeannette Cooperman holds a doctorate in American studies. As staff writer for St. Louis Magazine, she conducted a Q&A with Marie Griffith when Griffith arrived at Washington University and has watched the center’s growth with interest.