Measurements of an element in Earth and moon rocks have just disproved the leading hypotheses for the origin of the moon.

Tiny differences in the segregation of the isotopes of potassium between the moon and Earth were hidden below the detection limits of analytical techniques until recently. But in 2015, Washington University in St. Louis geochemist Kun Wang, then the Harvard Origins of Life Initiative Prize postdoctoral fellow, and Stein Jacobsen, professor of geochemistry at Harvard University, developed a technique for analyzing these isotopes that can hit precisions 10 times better than the best previous method .

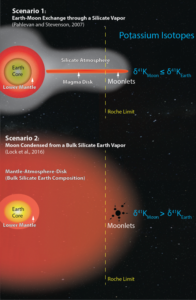

Wang and Jacobsen now report isotopic differences between lunar and terrestrial rocks that provide the first experimental evidence that can discriminate between the two leading models for the moon’s origin. In one model, a low-energy impact leaves the proto-Earth and moon shrouded in a silicate atmosphere; in the other, a much more violent impact vaporizes the impactor and most of the proto-Earth, expanding to form an enormous superfluid disk out of which the moon eventually crystallizes.

The isotopic study, which supports the high-energy model, was published Sept. 12 in the advance online edition of Nature. “Our results provide the first hard evidence that the impact really did (largely) vaporize Earth,” said Wang, assistant professor in Earth and Planetary Sciences in Arts & Sciences.

An isotopic crisis

In the mid-1970s, two groups of astrophysicists independently proposed that the moon was formed by a grazing collision between a Mars-sized body and the proto-Earth. The giant impact hypothesis, which explains many observations, such as the large size of the moon relative to the Earth and the rotation rates of the Earth and moon, eventually became the leading hypothesis for the moon’s origin.

In 2001, however, a team of scientists reported that the isotopic compositions of a variety of elements in terrestrial and lunar rocks are nearly identical. Analyses of samples brought back from the Apollo missions in the 1970s showed that the moon has the same abundances of the three stable isotopes of oxygen as the Earth.

This was very strange. Numerical simulations of the impact predicted that most of the material (60-80 percent) that coalesced into the moon came from the impactor, rather than from Earth. But planetary bodies that formed in different parts of the solar system generally have different isotopic compositions, so different that the isotopic signatures serve as “fingerprints” for planets and meteorites from the same body.

The probability that the impactor just happened to have the same isotopic signature as the Earth was vanishingly small.

So the giant impact hypothesis had a major problem. It could match many physical characteristics of the Earth-moon system but not their geochemistry. The isotopic composition studies had created an “isotopic crisis” for the hypothesis.

At first, scientists thought more precise measurements might resolve the crisis. But more accurate measurements of oxygen isotopes published in 2016 only confirmed that the isotopic compositions are not distinguishable. “These are the most precise measurements we can make, and they’re still identical,” Wang said.

A slap, a slug or a wallop?

“So people decided to change the giant impact hypothesis,” Wang said. “The goal was to find a way to make the moon mostly from the Earth rather than mostly from the impactor. There are many new models — everyone is trying to come up with one — but two have been very influential.”

In the original giant impact model, the impact melted a part of the Earth and the entire impactor, flinging some of the melt outward, like clay from a potter’s wheel.

A model proposed in 2007 adds a silicate vapor atmosphere around the Earth and the lunar disk (the magma disk that is the residue of the impactor). The idea is that the silicate vapor allows exchange between the Earth, the vapor and the material in the disk, before the moon condenses from the melted disk.

“They’re trying to explain the isotopic similarities by addition of this atmosphere,” Wang said, “but they still start from a low-energy impact like the original model.”

But exchanging material through an atmosphere is really slow, Wang said. You’d never have enough time for the material to mix thoroughly before it started to fall back to Earth.

So another model, proposed in 2015, assumes the impact was extremely violent, so violent that the impactor and Earth’s mantle vaporized and mixed together to form a dense melt/vapor mantle atmosphere that expanded to fill a space more than 500 times bigger than today’s Earth. As this atmosphere cooled, the moon condensed from it.

The thorough mixing of this atmosphere explains the identical isotope composition of the Earth and moon, Wang said. The mantle atmosphere was a “supercritical fluid,” without distinct liquid and gas phases. Supercritical fluids can flow through solids like a gas and dissolve materials like a liquid.

Why potassium is decisive

The Nature paper reports high-precision potassium isotopic data for a representative sample of lunar and terrestrial rocks. Potassium has three stable isotopes, but only two of them, potassium-41 and potassium-39, are abundant enough to be measured with sufficient precision for this study.

Wang and Jacobsen examined seven lunar rock samples from different lunar missions and compared their potassium isotope ratios to those of eight terrestrial rocks representative of Earth’s mantle. They found that the lunar rocks were enriched by about 0.4 parts per thousand in the heavier isotope of potassium, potassium-41.

The only high-temperature process that could separate the potassium isotopes in this way, said Wang, is incomplete condensation of the potassium from the vapor phase during the moon’s formation. Compared to the lighter isotope, the heavier isotope would preferentially fall out of the vapor and condense.

Calculations show, however, that if this process happened in an absolute vacuum, it would lead to an enrichment of heavy potassium isotopes in lunar samples of about 100 parts per thousand, much higher than the value Wang and Jacobsen found. But higher pressure would suppress fractionation, Wang said. For this reason, he and his colleague predict the moon condensed in a pressure of more than 10 bar, or roughly 10 times the sea level atmospheric pressure on Earth.

Their finding that the lunar rocks are enriched in the heavier potassium isotope does not favor the silicate atmosphere model, which predicts lunar rocks will contain less of the heavier isotope than terrestrial rocks, the opposite of what the scientists found.

Instead it supports the mantle atmosphere model that predicts lunar rocks will contain more of the heavier isotope than terrestrial rocks.

Silent for billions of years, the potassium isotopes have finally found a voice, and they have quite a tale to tell.