While the bacteria E. coli is often considered a bad bug, researchers commonly use laboratory-adapted E. coli that lacks the features that can make humans sick, but can grow just as fast. That same quality allows it to transform into the tiniest of factories: when its chemical production properties are harnessed, E. coli has the potential to crank out biofuels, pharmaceuticals and other useful products.

Now, a team from the School of Engineering & Applied Science at Washington University in St. Louis has developed a way to make the production of certain biofuels in E. coli much more efficient. Fuzhong Zhang, assistant professor in the Department of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering, along with researchers in his lab, have discovered a new method to cut out a major stumbling block to production process.

Their findings were recently published in the journal Metabolic Engineering.

“It’s a critical step that we’ve figured out how to solve this problem,” Zhang said.

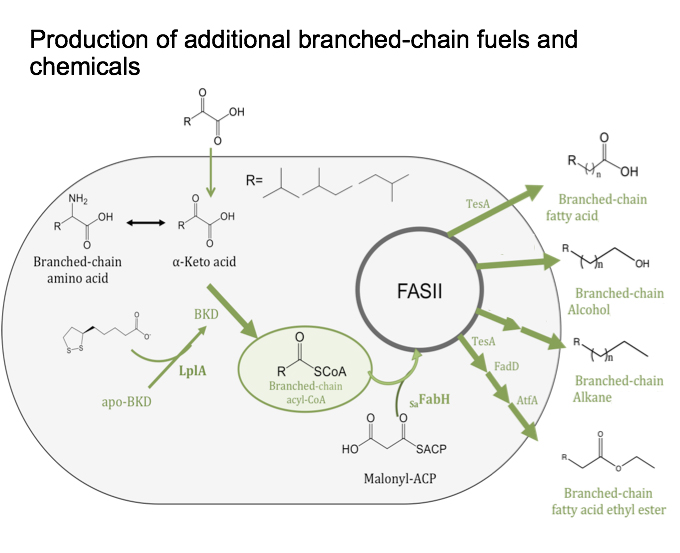

Branched-chain fatty acids (BCFA) are important precursors to the production of freeze-resistant or improved cold-flow biofuels. However, making it in bacterial hosts is difficult. It’s co-produced with different compounds called straight-chain fatty acids (SCFA), which have inferior fuel properties. Past attempts to engineer E. coli that churned out BCFA also made a large amount of SCFA, and made it difficult to isolate the BCFA for future use.

“From the process aspect, common bacteria produce mostly SCFA,” Zhang said. “That is really not the best fuel to use. Previously, the best you could do was a 20 percent BCFA concentration. Then you needed to use some additional chemical processes to separate the BCFA from the SCFA and enrich it. It consumes so much energy that it’s not cost-effective.

“Instead, our approach engineers this organism so it can produce something as close to 100 percent BCFA as possible,” he said.

Zhang’s lab has previously researched methods to reduce SCFA concentrations in E. coli. This newest paper further improves upon that work. By developing two different protein pathways that chemically affect the bacteria, Zhang’s team fixed what it called a bottleneck in the BCFA production line. The protein pathways enabled the E. coli to boost its BCFA manufacture to 80 percent of all fuel products.

“It’s a higher quality,” said Gayle Bentley, a doctoral student in Zhang’s lab, and the paper’s lead author. “A lot of people have been making these SCFA fuels, and while that’s important work, they don’t have the improved qualities like we’re generating. The difference is quite significant.”

Now that the chemical workaround has been discovered, Zhang and Bentley said the applications for their work have potential to expand to other products derived from fatty acid compounds.

“The compounds we’ve made as fatty-acid forms are beneficial as a nutraceutical, effective as an anti-tumor compound,” Bentley said. “It’s also been shown to be effective to prevent and treat neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. These compounds are really expensive to derive from their original source but using this platform may actually make it more economically feasible.”

Said Zhang: “We really think this is an important step toward a platform that can offer a variety of different products for different applications.”

Zhang is a past recipient of young faculty awards from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA); the National Science Foundation; NASA; and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. He and his lab are working with the Washington University Office of Technology Management (OTM) in regards to patent filing and licensing efforts for the new technology.

Both researchers are available for interviews. Zhang may be reached at fzhang29@wustl.edu; Bentley at gbentley@wustl.edu.