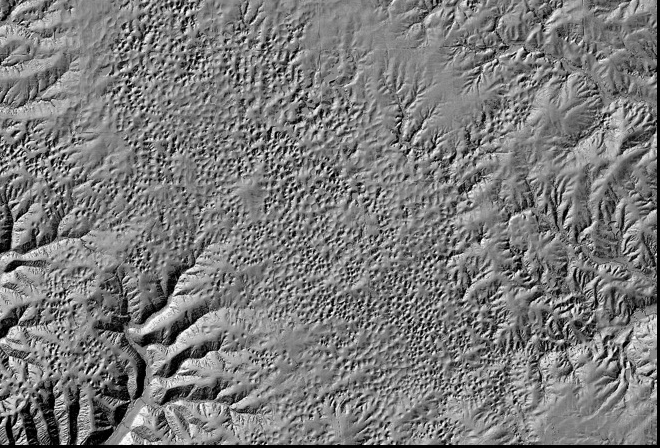

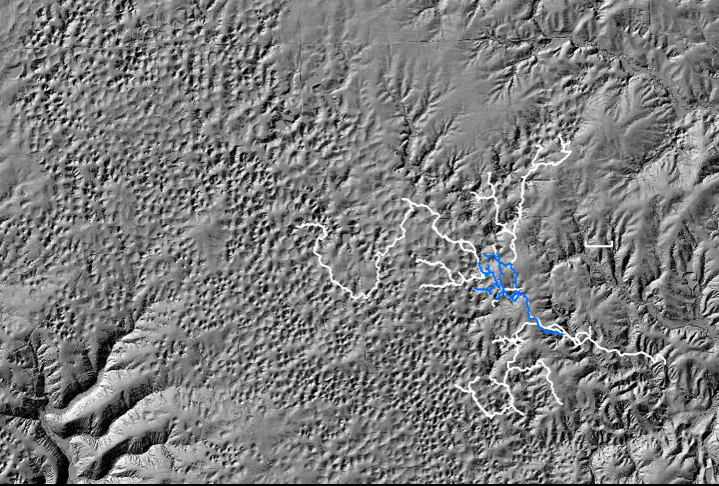

If you could magically strip the trees, crops and other ground cover off southwestern Illinois, this is what you’d see:

Lidar (light detection and ranging) image of Monroe County, Illinois, reveals thousands of sinkholes.

Lidar (light detection and ranging) image of Monroe County, Illinois, reveals thousands of sinkholes.

The image above was made by firing laser pulses and recording those that traveled literally between leaves and bounced back to a sensor on an overflying airplane.

Aaron Addison, director of scholarly services of University Libraries at Washington University in St. Louis and a lifelong caver, points out that while surface drainage (stream beds) can be seen to the east of the central plain in the image, there are only sinkholes — thousands of them — on the plain itself. All the rain that falls there disappears, draining underground toward the Mississippi River.

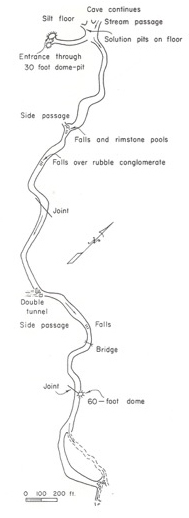

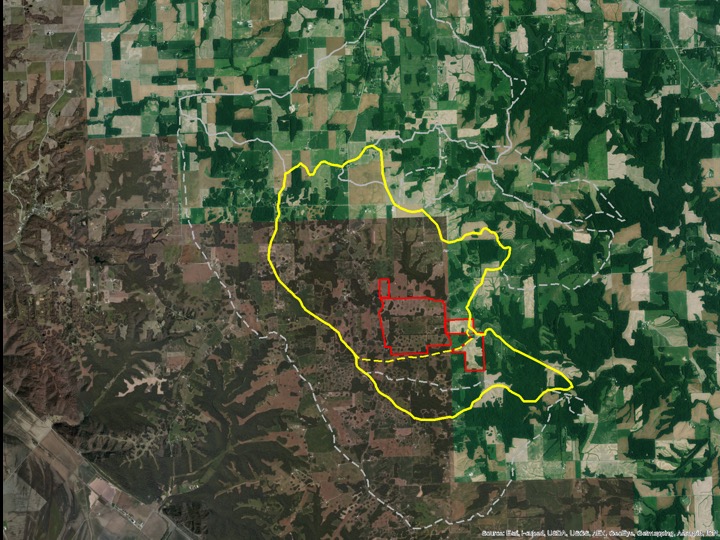

Addison and fellow cave explorer Bob Osburn, laboratory administrator for the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Arts and Sciences, and others — both at the university and with volunteer organizations in Illinois — are currently mapping the huge, branching drainage system that underlies the plain that is called Fogelpole Cave.

The sinkhole plain is located just below the notch in the west side of Illinois, where Mississippian limestones are exposed at the surface.

“If you go over to Illinois and start looking at rocks you’re not going to see limestone,” Osburn said. “Almost all of Illinois is buried under glacial deposits of one kind or another.

“But just a little south of the spot where St. Louis docks into Illinois, you come to area where there are more or less flat-lying Mississippian limestones at the surface. When you have flat-lying limestone at the surface, water tends to get into it, go down to a bedding plane at some lower level, migrate and come out wherever creeks cut across that patch of rock. Those conditions create what’s called sinkhole plain caves.”

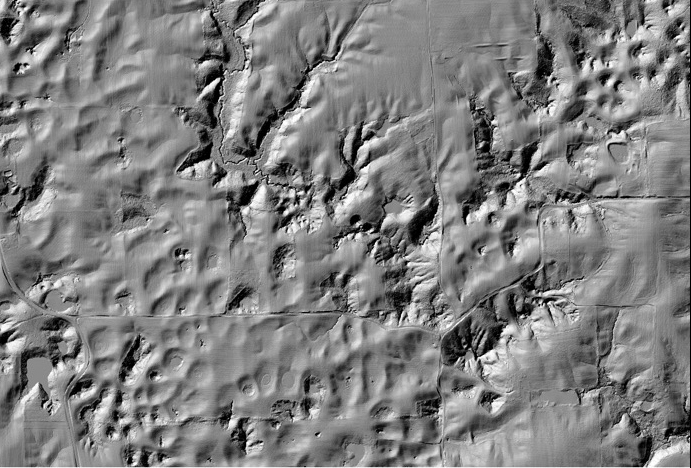

This close-up lidar image suggests what might lie beneath the sinkhole plain. “Look at the valley that drops down from the upper border, close to the middle,” Addison said. “It comes down about a third of the vertical distance and then just stops. All of the water goes underground there and does not show up again until it bubbles up in a spring that’s off the bottom of the slide.”

This close-up lidar image suggests what might lie beneath the sinkhole plain. “Look at the valley that drops down from the upper border, close to the middle,” Addison said. “It comes down about a third of the vertical distance and then just stops. All of the water goes underground there and does not show up again until it bubbles up in a spring that’s off the bottom of the slide.”

By 2014, the sinkhole plain was threatened by urban sprawl, much to the dismay of people who knew the land. “If you start putting septic all over a sinkhole plain, guess where the sewage goes when it floods?” Addison said. “It all goes straight into the caves.”

So when a farm that overlies much of the known cave came up for sale a few years ago, local residents banded together into a group called Clifftop and raised enough money from grants and donations to buy the $3 million property. The property, called the Paul Wightman Subterranean Nature Preserve, is now protected from development in perpetuity.

In June 2014, Clifftop, the Illinois Speleological Survey and about a dozen volunteers from Washington University began to re-survey the cave to produce a detailed base map for all future research.

This past May, Addison and Osburn gave a talk to update department members on the 15 or so survey trips that have been made so far.

The importance of light discipline

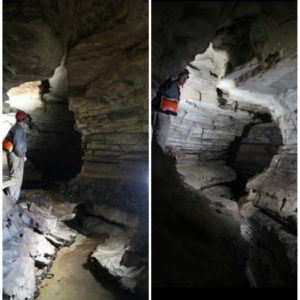

What is it like being in Fogelpole? “Well,” said Osburn, who has been a caver for 40 years, “it is dark.”

“So light (and light discipline) are the No. 1 concern,” Osburn said. “You must never be without light or you will be unable to get back out. LED lights have made having enough hours of light much easier as a battery or charge lasts so much longer.

“The temperature is always 55 or 56 degrees Fahrenheit. How cold that is depends on who you are, and how wet you are. Some people are fine with no thermal layers, others wear two or three.

“Most people are comfortable in pants and a long-sleeve shirt, but if you have to wade in the water (which you usually do) then poly-pro underwear or a wetsuit is a good idea.

“The work is generally slow, and most of the crew has to wait periodically for the bookkeeper to catch up,” Osburn said.

In some places, the cave floor is covered with breakdown, slabs of rock that have spalled off the ceiling or walls. Breakdown can be hazardous to cavers, but not in the way you might think. Your chances of being hit by a block are very small. On the other hand, because these piles of rock are not subjected to the wind and weather that cause surface talus to settle, they can be unstable. “I have seen a guy step up onto a desk-sized slab that rocketed down a breakdown pile with him on top until he finally had the wit to jump off,” Osburn said.

“We see few creatures, and those we do see are small, live more slowly than surface life –sometimes for a long time but slower — they forage more efficiently and often have given up things like pigment and eyes.

“In Fogelpole, we have seen some amphipods that are cave-adapted, a few frogs and fish (surface varieties washed-in), salamanders and not much else.

“Because access to the cave is restricted by gates or strict landowners, we’ve never seen people, although we’ve seen signs of people (footprints and graffiti).

“This is probably just as well. Back when I first started caving we not too infrequently met other people in caves, sometimes in need of rescue. People who had run out of light, or gone down climbs they could not get up, often cold, sometimes crying, etc.

Keep calm and take good notes

People have probably entered Fogelpole Cave as long as they have lived in the area, but the cave was re-discovered in the 1940s by Paul Wightman, who grew up in nearby Waterloo, Ill.

Whiteman, who later became a Catholic priest, reported the caves he found to J. Harlen Bretz, author of “The Caves of Missouri,” who published the first map of Fogelpole Cave in 1961.

Wightman encouraged the Fogelpole family, which owned the main cave entrance, to limit visitors to those with a scientific interest in the cave, limiting damage to the cave.

“After that, not much happened in the cave for many years,” Addison said. “ It wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that people went back in the cave for the purposes of research.”

As an undergraduate at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, Addison joined a local caving club that documented features of the cave, including an endangered species of bat. Their discoveries prompted the state to purchase the land surrounding the main entrance to the cave, which became the Fogelpole Cave Nature Preserve in 1989.

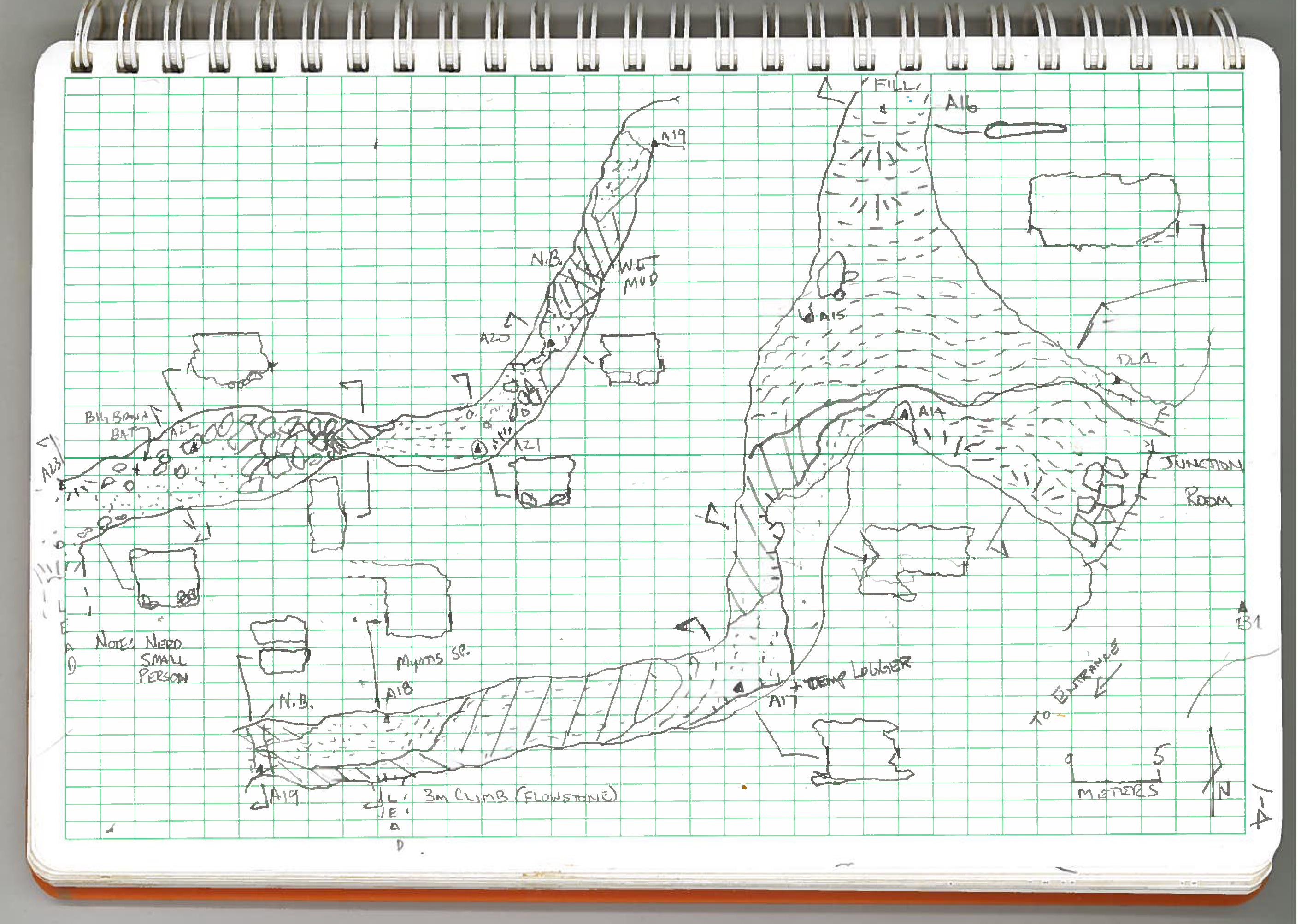

During his presentation, Addison showed the group, which included many geology students, field notes made at that time and told them that “by today’s standards the notes are not acceptable because there’s no real detail,” he said.

“I can read some of the notes, but not others. As a result, a lot of this is wasted effort. The surveying has to be repeated because the field data weren’t good enough.”

Following the water

We know more than we might about the internal plumbing of the sinkhole plain, Addison said, because in 2000 Illinois hired a contractor to do dye-tracing in the area.

Dyes so strongly fluorescent they were detectable in low concentrations are mixed with water and injected in a sinkhole. The dye is absorbed downstream by activated charcoal packets called dye “bugs“ that are taken to a lab for analysis.

Addison points out the many small dots in the aerial map of the recharge areas. “Those are wooded sinkholes,” he said. “They just kind of pop out because they aren’t plowed; you can’t drive your tractor into a sinkhole and expect it to survive.”

The dye tracing showed that underground connections are much more extensive than the known cave. In fact, it suggested that all of the sinkholes in the plain probably feed into Fogelpole or nearby caves.

Whether all of these connections are big enough to be explored is another question. But even if many of them are not, the team looks forward to several more years of expeditions to Illinois.

Addison (aaddison@wustl.edu) and Osburn (osburn@wustl.edu) have also mapped lava tubes in the Galapagos Islands, a giant river cave in Laos, and Mammoth Cave in Kentucky. For them, this is like backyard camping: lots of fun and no dinner-plate-sized spiders.