A study led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, in collaboration with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, has identified a genetic error that weakens the aorta, placing patients with this and similar errors at high risk of aortic aneurysms and ruptures. The findings will help diagnose, monitor and treat patients with aortic disease not caused by well-known conditions, such as Marfan syndrome and other genetic mutations known to disrupt connective tissues.

The study appears July 18 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Working with the Brigham Genomic Medicine Program, the researchers identified the mutation in a family with a history of aortic disease but no known genetic reason for the condition. The error is in a gene called lysyl oxidase (LOX), which Washington University researchers have shown is responsible for connecting networks of tissue fibers that make up blood vessels.

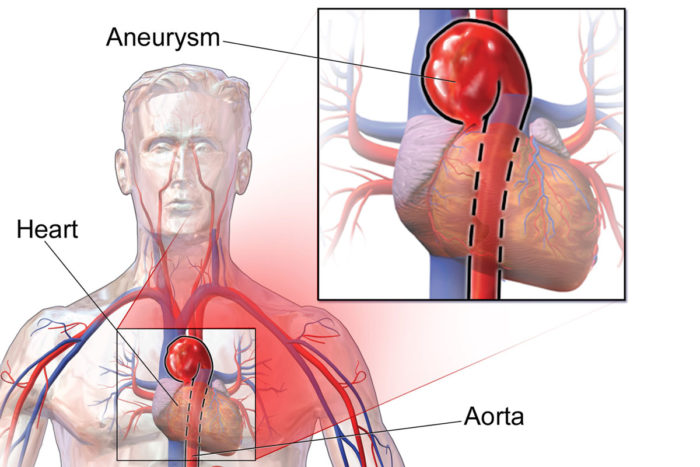

The aorta is the body’s largest artery that carries blood from the heart to the rest of the body. A lifetime of smoking and poor cardiovascular health can lead to aortic aneurysms in older adults. But bulging and tearing of the aorta in a young person is most often due to an inherited condition.

A number of genetic mutations, including those that cause Marfan syndrome and Loeys-Dietz syndrome, are known to interfere with the integrity of connective tissues. Such weakening puts patients at high risk of death from a ruptured aorta. Standard genetic tests often pinpoint the reason for inherited aortic disease, but such tests can’t explain all cases.

“When a patient comes to the clinic with an enlarged aorta, clinicians can evaluate a standard list of genes to look for a cause of the condition,” said senior author Nathan O. Stitziel, MD, PhD, a Washington University cardiologist and assistant professor of medicine. “Lysyl oxidase should now be added to the standard test panel. This type of information can provide clarity for families with histories of unexplained aortic aneurysms.”

The findings also may allow affected individuals to be identified early, before the aorta begins to enlarge, so that doctors can help these patients take steps to lower pressure on the aorta, and decide when surgery may be required to prevent a sudden rupture.

To confirm that this mutation was the cause of the weakened aorta rather than an association, Stitziel and his colleagues recreated the genetic mistake in mice using the gene editing technology CRISPR. Washington University’s Robert P. Mecham, PhD, the Alumni Endowed Professor of Cell Biology and Physiology, and graduate student Vivian Lee showed that mice with two copies of the mutated gene died of aortic rupture at birth. Mice with only one copy — like members of the family the researchers identified with the mutation — had disrupted collagen and elastin fibers in the aorta.

“The layers and fibers of the aorta are almost like the belts inside a tire,” Stitziel said. “You have to have the right structure to maintain the strength and integrity of the artery. Lysyl oxidase crosslinks the fibers together. When there is less lysyl oxidase than there should be, the proper structure is disrupted. And when lysyl oxidase is absent altogether, the mice don’t survive after birth.”

Stitziel added that the mouse model of the condition will enable the researchers to test new potential therapies for this type of aortic disease. In particular, the investigators pointed out that lysyl oxidase is known to perform its job of crosslinking fibers better when bound to copper, raising the possibility that such patients may benefit from therapies involving dietary copper.

“When we found this causal gene and were able to reveal it to the family, it was an emotional moment,” said Natasha Frank, MD, a clinical geneticist who treated several members of the family at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “Using genetic sequencing, we were able to answer the kind of question that hasn’t been possible to address before and potentially change the lives of family members who can now be tested for mutations in this gene.”