Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have found a way to give photons, or light packets, their marching orders.

The researchers have capitalized on the largesse of an energy state in an optical field to make photons in their lasing system travel in a consistent mode, either clockwise or counterclockwise.

Consistency in light propagation is important to get a reliably strong photonic signal and light pulse for all lasing systems and applications. Lasing alone is a multibillion-dollar industry with thousands of applications from communication to medicine to hair removal. Yet this consistency also behooves present and future optical sensing devices, be they aerosol detectors or cancer spotters.

Lan Yang, the Edwin H. & Florence G. Skinner Professor of Electrical & Systems Engineering, and Şahin K. Özdemir, research associate professor, both in the School of Engineering & Applied Science, along with collaborators Stefan Rotter at Vienna University of Technology in Austria and Jan Wiersig at Otto-von-Guericke University in Germany, have exploited the benefits of a physical phenomenon called an exceptional point to force photons to go either clockwise or counterclockwise instead of both directions randomly.

Findings were published June 6 in an early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

An exceptional point arises in physical fields when two complex eigenvalues and their eigenvectors coalesce, or become the same. These are mathematical tools that describe a physical system. Think of the exceptional point as a complex bewitching environment where often unpredictable and counterintuitive phenomena occur.

For instance, in a 2014 paper in Science, Yang and Özdemir described harnessing the exceptional point to add loss to a laser system to actually gain energy – to gain by losing, if you will. The exceptional point has contributed to a number of counterintuitive activities and results in recent physics studies with more certain to come.

Yang and Özdemir induced the existence of an exceptional point in an optical field through insertion of two silica scatterers, or nanotips, which help to create the perfect storm that conjures up an exceptional point. Using nanopositioning systems, Bo Peng, then a doctoral student and one of the lead authors of the 2014 Science paper, tuned the distance between the scatterers and increased their relative size in the optical field to perturb the microresonator and beckon an exceptional point. Thus, they have a controllable system.

“One of the exciting things of this research is it presents an on-demand control of the laser,” Yang said. “By changing the scatterer location, you can change the operating regime. This opens the possibilities for new functional devices based on lasers.”

“This finding further enhances our capability to harness microlasers, not only by power boost with loss, as we achieved previously, but also by precisely controlling the lasing direction now,” Peng said.

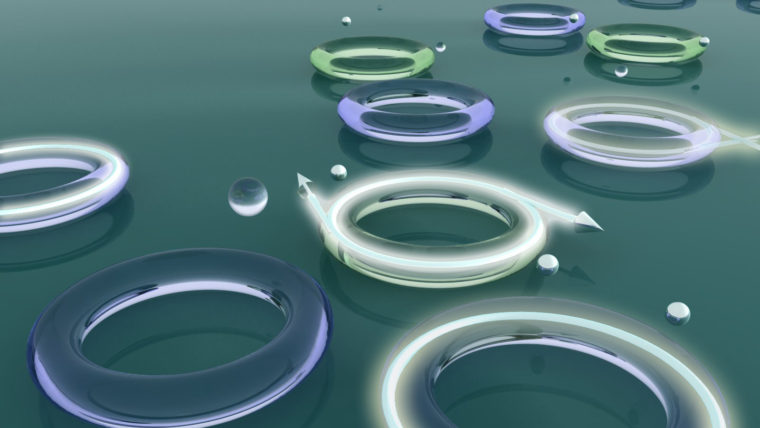

The microresonator they use is in a class called whispering gallery mode resonators (WGMRs) because they work similarly to the renowned whispering gallery in London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, where a person on one side of the dome can hear a message spoken to the wall by a person on the other side. The WGMR device does a similar thing with light frequencies rather than sound.

Light is injected into and coupled out from the WGMR through tapered fiber waveguides on either side. Nanopositioners control the scatterers, which probe the chirality of the WGM. In the absence of the scatterers, when light is injected into the WGMR in the clockwise or counterclockwise directions: A resonance peak appears in the transmission and no signal can be obtained in the reflection.

“When the system is brought to an exceptional point by the help of the scatterers, this situation changes” Özdemir said. “The reflection shows a pronounced resonance peak for only one of the injection directions. This asymmetric reflection is a distinguishing characteristic of chirality, an intrinsic property of a mode.”

There can be multiple exceptional points in a physical system.

“Bringing the system to a different exceptional point results in the appearance of a reflection peak only for the other injection direction,” Özdemir said.

Added Yang: “Thus, we can control the chirality of a mode by going from one exceptional point of the system to another.”

The team then established the link between asymmetric reflection at exceptional points and the intrinsic chirality of lasing modes. For this purpose, they used an erbium-doped WGM microresonator. Erbium serves as a kind of doping agent that encourages laser activity at a wavelength different than the light that is used to excite lasing.

In the absence of an exceptional point, the emitted light from the erbium into the WGM resonator can go clockwise and counterclockwise simultaneously. This makes extraction of the laser light from WGM microlasers inefficient. At an exceptional point, the photons will move in a consistent way either in the clockwise or counterclockwise.

“We now have a control on the chirality of the whispering-gallery modes and hence the emission direction of lasing thanks to the exceptional points,” Yang said. “Where we place the scatterers and how big we make them changes the operating regime, adding to the technique’s versatility.”

“We can tune the whispering-gallery-modes to have a bidirectional (both clockwise and counterclockwise directions) microlaser or a unidirectional laser with emission in the clockwise or counterclockwise direction. We can completely reverse the emission direction by transiting from one exceptional point of the system to another exceptional point,” Özdemir said.

The results provide WGMR systems new functions that will be useful for lasing, sensing, optomechanics and quantum electrodynamics.

“The findings of the team prove yet again that if engineered properly, exceptional points, and thus engineering of loss and scattering, provide new tricks for optical sciences to solve problems, which have hindered progress and limited the usefulness of devices,” Yang said.

“This finding further enhances our capability to harness microlasers, not only by power boost with loss, as we achieved previously, but also by precise control of the lasing direction now,” Peng said.

The researchers say their findings will help develop novel technologies for controlling light flow, pave the way to chiral photonics on chip and could affect scientific fields beyond optics. They have already set to show and use other counterintuitive features of non-Hermitian photonics at the exceptional points.