The August 2014 death of unarmed Michael Brown at the hands of Ferguson, Mo., police officer Darren Wilson captivated the nation and touched off a heated debate about the nature of law enforcement in the United States.

A new book edited by Kimberly Norwood, professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis School of Law, and of African & African American Studies in Arts & Sciences, explores the underlying fault lines that cracked and gave rise to the eruption in Ferguson.

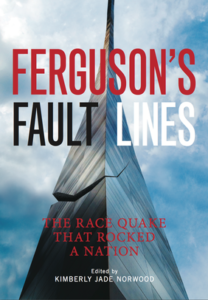

The book, “Ferguson’s Fault Lines: The Race Quake That Rocked a Nation,” was published by ABA Publishing and released this month.

The book, “Ferguson’s Fault Lines: The Race Quake That Rocked a Nation,” was published by ABA Publishing and released this month.

“I started thinking about Michael Brown’s education right after his death,” Norwood said. “He graduated from a very academically troubled school district. I thought about his life prospects, had he lived, given the level of education provided by his school district. I was troubled with how we as a society failed him before he even had a chance to succeed.”

Almost immediately, Norwood said, she realized the multiple systemic failures that surrounded him: poverty, inadequate and segregated housing, poor mental and physical health outcomes and access to care, crime, aggressive and, according to the Department of Justice, racially biased policing.

“I wanted the world to get an understanding of these multiple oppressive layers that surround and weigh on individuals and entire communities, and how these pressures — fault lines as I see them — can result in a perfect storm,” she said.

“In this small community of Ferguson, with this kind of undue pressure from almost every angle, eruption was really a matter of time. People need to know this. See it. Hopefully try to understand it and be motivated to do something; to do better.”

The book’s chapters tackle issues ranging from grand jury proceedings to housing segregation to disparities in mental and physical health.

“Ferguson is unprecedented,” Norwood said. “Yes, we have had riots and protests in our nation’s past. But this was different. It started in a very small community and not only spread nationwide, but worldwide. We haven’t seen that kind of effect, really, ever. Obviously social media has a lot to do with that. Social media broadcast to the world, in real time, the cries of a community.

“I can only hope that we don’t close our collective eyes and ignore the massive lessons we certainly learned from Ferguson,” she said. “The divide between the haves and have-nots is growing, almost exponentially. And the have-nots far outnumber the haves. Doing nothing is in no one’s best interest.”

The book is an interdisciplinary project, with lawyers, law professors, social scientists and journalists all contributing.

“We hope this book will provide the reader with some understanding of the underpinnings of the eruption in Ferguson, and some understanding of the ripple effects we saw nationwide and worldwide,” Norwood said. “We hope that someone, somewhere learns from our very broken system and helps to clear paths for change.

“Otherwise Ferguson will erupt again. Not only Ferguson, Missouri, but in similar cities and suburbs, with similar pressures, as they currently exist throughout our nation.”