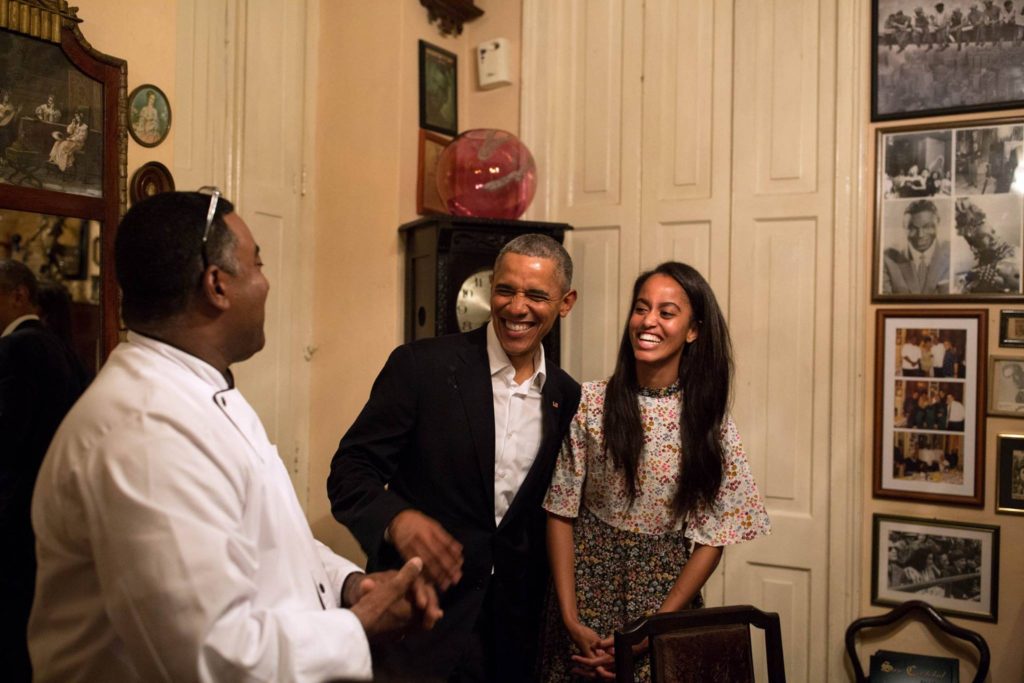

Pope Francis, President Obama, the Rolling Stones, Major Lazer — today it seems everybody is going to Cuba.

Yet as the world marvels at the reestablishment of diplomatic relations, it is important to put recent changes in historical perspective, said Elzbieta Sklodowska, the Randolph Family Professor of Spanish in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Since Raul Castro took over as president in 2008 (de facto in 2006), Cuba has undergone countless reforms, easing the grip of the regime on the lives of its citizens,” said Sklodowska, who is working on a book about Cuban literature, art and film since the collapse of the Soviet system in 1991.

“Cubans can now travel abroad more freely, they can own, buy and sell real estate property, they can open private businesses or catch a Wi-Fi connection — albeit slow and unreliable — in one of the 50-plus hot spots scattered throughout the island,” Sklodowska said.

“To all of us who take all this for granted, it may sound like too little too late. But instead of focusing on the snail-like pace of Cuban reforms, perhaps we should be more impatient about the U.S. embargo, imposed in 1960; or about the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, which has been ‘leased’ by the United States since 1903.”

Though the embargo of course remains in place, Sklodowska, with colleague Joseph Schraibman, has been taking students to Cuba over spring break since 2001. She notes that the relative thaw has simplified questions of travel, and not just for presidents and rock stars.

“Right now, there are about a dozen categories under which a U.S. citizen can get a waiver from the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, which controls travel to Cuba from the United States,” she said. “Simply by checking one of the boxes in the OFAC form, many people are able to qualify to travel legally on direct charter flights to Havana from Miami, Tampa, Los Angeles and a few other locations.”

Yet this new openness, with its promise of increased tourism and economic opportunity, also poses important questions about the island’s future.

“Is Cuba’s economy going to become dependent, again, on a single industry?” Sklodowska asked. “How will the development of tourist infrastructure impact Cuba’s natural environment? Can the economic benefits be distributed throughout the island, or will they merely be concentrated in Havana?

“With Cuban art flooding international galleries, museums and private collections, are the artists doomed to also sell their souls to the market? And when will we see the first Nobel Prize in Literature for one of Cuba’s many outstanding contemporary writers?”