Ask Americans to name the former U.S. president whose face currently graces the U.S. $10 dollar bill and most will be quick to answer Alexander Hamilton.

Sure, it’s a trick question. But a new study from memory researchers at Washington University in St. Louis confirms that most Americans are confident that Alexander Hamilton was once president of the United States.

“Our findings from a recent survey suggest that about 71 percent of Americans are fairly certain that Alexander Hamilton is among our nation’s past presidents,” said Henry L. Roediger III, a human memory expert at Washington University. “I had predicted that Benjamin Franklin would be the person most falsely recognized as a president, but Hamilton beat him by a mile.

“The interesting thing is that their confidence in Hamilton having been president is fairly high — higher than for six or so actual presidents.”

Roediger, PhD, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Arts & Sciences, has been testing the ability of undergraduate college students to remember the names of presidents since 1973, when he first administered the test to undergraduates while a psychology graduate student at Yale University.

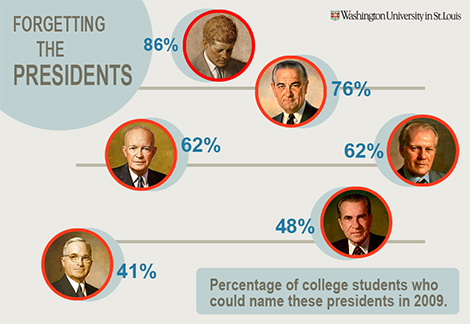

Roediger’s 2014 study in the journal Science suggests that we as a nation do fairly well at naming the first few and the last few presidents in the order they served. But our recall abilities then fall off quickly, with fewer than 20 percent able to remember more than the last eight or nine presidents in order.

The focus of the current study is a bit different, said Roediger, because it’s designed to gauge how well Americans can recognize the names of past presidents, as opposed to the much greater challenge of directly recalling them from memory and listing their names on a blank sheet of paper.

This study, published online this week in the journal Psychological Science, is co-authored by K. Andrew DeSoto, a former psychology graduate student at Washington University who is now a research methodology fellow at the Association for Psychological Science.

“Our studies over the past 40 years show that Americans can recall about half the U.S. presidents, but the question we explore with this study is whether people know the presidents but are simply unable to access them for recall,” Roediger said.

The current study is based on a name recognition test administered to 326 people via Mechanical Turk, an interactive online service operated by Amazon.

Participants were asked to identify past presidents when presented with a list of names that included actual presidents and non-presidents, such as Hamilton and Franklin. The lists also presented other false items, including familiar names from American history and non-famous common names, such as Thomas Moore. With each president-or-non-president response, participants indicated their level of certainty on a scale of zero-to-100, where 100 was absolutely certain.

The rate for correctly recognizing the names of past presidents was 88 percent, well above recall but far from perfect. Franklin Pierce and Chester Arthur were recognized less than 60 percent of the time. Hamilton was more frequently identified as president than several actual presidents, and people were very confident when saying he was president (83 on the 100-point scale).

The study identified three other prominent figures from American history that more than a quarter of those surveyed incorrectly recognize as past presidents, including Franklin, Hubert Humphrey and John Calhoun.

Perhaps more striking, nearly a third of those surveyed falsely recognized the common name “Thomas Moore” as someone who was once an American president.

Humphrey served as vice president and ran for president in 1968. Franklin was a famous American involved in the events surrounding the founding of the country and served as ambassador to France. Calhoun was a senator and vice president for seven years.

“These factors may account for their general familiarity in American history, but if subjects cannot recollect their roles, then false recognition as president may occur because subjects cannot oppose the high name familiarity with knowledge of their actual roles,” Roediger said. “John Calhoun is a surprise, because he was a supporter of states rights and slavery, but apparently people remember the name but not why they know it.”

The high false alarm rate for Thomas Moore, however, came as another surprise to the researchers. People with this name have served in the U.S. House of Representatives, but none are particularly famous.

“Our best guess is that the Anglo-Saxon structure of his name, the frequency of both parts of the name, and possibly his confusability with Sir Thomas More, the counselor to King Henry VIII, may have contributed to the name’s familiarity and false recognition,” Roediger said.

Roediger and DeSoto suggest that our ability to recognize the names of famous people hinges on those names appearing in a context that’s related to the source of their fame.

“Elvis Presley was famous, but he would never be recognized as a past president,” Roediger said. “Most of the names in our study that were falsely recognized as belonging to past presidents are those with strong ties to American history. These same individuals would not be recognized if the task were to recognize famous musicians from the 1960s. It’s not just enough to have a familiar name, but it must be a familiar name in the right context.”

This study adds to an emerging line of research that focuses on how people remember history — a field called collective memory or historical memory.

A striking detail emerging from recent studies by Roediger and DeSoto is that the ability of people to remember the names of presidents follows very consistent and reliable patterns.

“No matter how we test it — in the same experiment, with different people, across generations, in the laboratory, with online studies, with different types of tests — there are clear patterns in how the presidents are remembered and how they are forgotten,” DeSoto said.

While many of these patterns can be explained using decades-old theories of memory, the findings are also sparking new ideas about how lasting fame is shaped by the nuances of human memory function.

“Even on a recognition test, knowledge of American presidents is imperfect and prone to error,” Roediger said. “The false recognition data support the theory that false fame can arise from contextual familiarity. And our recall studies show that even the most famous person in America maybe be forgotten in as short a time as 50-75 years.”