The first time a parent told Elizabeth Petersen not to teach evolution, she caved. No, she did not skip Charles Darwin’s concept altogether. But she avoided the “E word,” opting instead for phrases such as “natural selection” and “adaptation.”

“That parent intimidated me,” said Petersen, who taught seventh-grade science. “I was so shocked, I didn’t know how to respond.”

The next time a parent objected, Petersen was ready. She taught her lessons as planned while the student studied in the library.

“The parents wanted me to give their son alternate reading assignments,” Petersen said. “Well, there are no alternate readings for evolution. It is the foundation of all biology.”

Eventually, the student returned to class. But first, Petersen asked to meet with the parents.

“I wanted to show them what their child missed,” Petersen said. “I took them through the unit and discussed how body parts are adapted to different environments and functions. They looked at each other and said, ‘OK, we don’t have a problem with this.’ Then I explained how certain traits are selected for and they said, ‘We don’t have a problem with that either.’ I was able to address their misconceptions and show them evolution is not scary.”

Petersen is lucky. In her 18 years at the Ladue School District, one of the highest achieving and most affluent districts in Missouri, she was challenged only these two times.

But other evolution educators continue to face resistance from parents, lawmakers and school boards. A recent Pew Research Center survey on science and society shows that one-third of the population denies evolution.

“There is a chilling effect,” said Victoria May, executive director of the Institute for School Partnership (ISP) at Washington University in St. Louis, which serves local schools through professional development and curricula. “When a small but vocal minority objects, some schools decide it’s just easier avoid the subject all together.”

That’s why the ISP annually offers a free program called Darwin Day, which equips K-12 science teachers with the confidence and skills to teach evolution. This year’s will be held Saturday, Feb. 13. Timed to the anniversary of Darwin’s birth — the 207th this year — the event features workshops, lesson plans and presentations from leading biologists.

And cake.

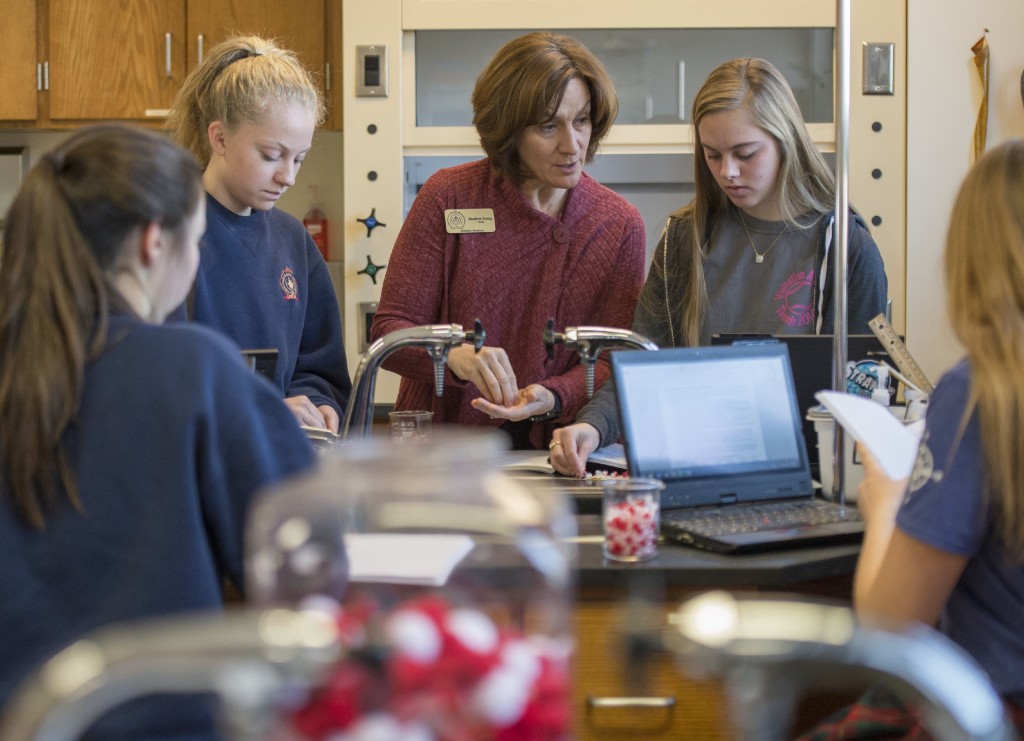

“A birthday party is a fun way to broaden our reach,” said Heather Essig, who teaches sixth-grade science and AP biology at Visitation Academy, an independent, Catholic girls’ school. “Teaching biology can be pretty isolating. You are often the only person in the school doing it. Darwin Day is great because it connects teachers to the recent science and gives us an opportunity to network and share ideas.”

In addition to Darwin Day, ISP hosts the Evolution Education Book Club, which features both academic and popular titles such as “Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body” by Neil Shubin; and “In the Light of Evolution: Essays from the Laboratory and Field,” by Harvard biologist Jonathan Losos, who will speak at the 2016 Darwin Day. David Kirk, PhD, professor emeritus in the Department of Biology in Arts & Sciences, leads the club.

“Pushback from evolution deniers is just one of the challenges science teachers face,” Kirk said. “They also must keep up with science that changes daily.”

As a researcher, Kirk studied spherical green alga known as volvox. Today, he commits his time and money to improving evolution education. He supplies the books for the book club, buys Darwin Day attendance prizes (polished fossils this year) and funds the Kirk Teacher Fellowship, which supports a local leader in evolution education.

Petersen was the first Kirk Fellow. Today, she teaches ISP professional development workshops across the region and advocates at the state level for better science standards. Essig is the current Kirk Fellow and winner of the Loeb Prize for Excellence in Teaching Science and Mathematics. At the start of every school year, she asks her students to take a walk in the woods.

“I tell them, ‘I promise you, the woods will look completely different after this class,’” Essig siad. “They come back and say, ‘Everywhere I go I keep thinking of biology.’ ”

Now compare Essig with Kirk’s high school science teacher. He refused to teach evolution, not because he didn’t accept it, but because of parents like Kirk’s.

“My dad told me when I went to college, ‘They are going to try to teach you about evolution. Don’t believe a word they say,’ ” Kirk said. “So who can blame my teacher?

“The sad thing is, decades later, polls show that many teachers who accept the importance of evolution still do not incorporate it in their classes at all or reduce it to one lecture because they are afraid. And yet, we know you can’t teach 20th-century biology, let alone 21st-century biology, without evolution.

“It’s a national problem,” Kirk said.