A disproportionate number of the children injured or killed were poor, male and African-American. The data, gathered from 2008 to 2013, mirror trends in other urban cities. However, the fatalities cited in the study do not include children who died at the scene, on the way to the two emergency rooms, or at other nearby medical centers.

The study offers a picture not only of the frequency of such incidents but of the circumstances that contributed to the injuries and deaths. Such knowledge, the researchers believe, can help identify risk factors and stem gun-related injuries.

The findings will be published in January in The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery.

“Children getting injured by firearms is a major health crisis in this city,” said Martin S. Keller, MD, the study’s senior author and an associate professor of surgery at the School of Medicine. “St. Louis is the focus of this study; however, it’s representative of many other regions in the U.S.”

Among the study’s findings:

- Of the 398 children treated, almost 78 percent were African-American.

- About 82 percent of all firearm injuries, including deaths, occurred among boys. The majority were African-American, with a median age of 15.

- Fifteen also was the median age of victims injured in shootings designated as assaults. Most victims of accidental shootings, on the other hand, were younger, with a median age of 12.5 years.

- Thirty-five percent of the injuries resulted from accidental shootings, with the remaining injuries caused by assaults.

- Nearly 75 percent of accidental shootings occurred in the home. Of those, almost 38 percent were self-inflicted, and about 40 percent were caused by people the victims knew.

- The majority of firearms used were handguns.

Despite a regional decrease in the overall incidence of gunshot wounds during the five-year period, statistical trends for 2013 and 2014 suggest that the number of firearm deaths and injuries in the overall population, including children, has increased, with cases of firearm-related violence, including aggravated assault, rising significantly.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 35,000 children ages 19 and under have died since 1999 due to firearm injuries, and about 10,000 each year are treated for such injuries.

“If we take a public-health approach to the problem and treat gun violence like we would any other danger facing children, we could decrease gun injuries and deaths,” said Keller, medical director of trauma at St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

Keller and Pamela M. Choi, MD, the study’s lead author and a general surgery resident at the School of Medicine, analyzed electronic medical records and hospital trauma registries from 2008 to 2013 regarding firearm victims ages 16 and under who were treated at one of the region’s two Level 1 pediatric trauma centers: St. Louis Children’s Hospital or Cardinal Glennon Medical Center.

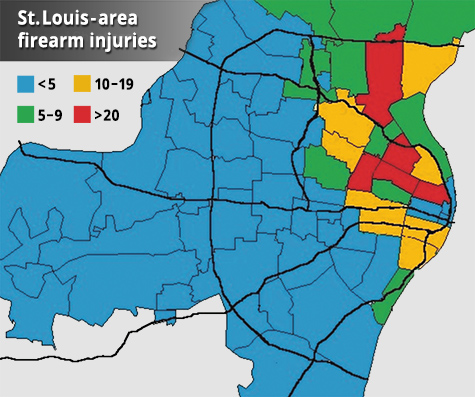

Researchers also analyzed 94 ZIP codes in the St. Louis region, a 250-square-mile area that encompasses eastern Missouri and southern Illinois and includes urban, suburban and rural communities. Accidental shootings were seen across the region, compared with intentional shootings that clustered in certain areas.

“This shows that accidental shootings can happen anywhere,” Keller said. “No community is immune.”

Keller said the data on accidental shootings also point to the need for preventive education. “I’ve talked to family members of victims who had hidden loaded guns in so-called safe places, and they were shocked when the children found their guns,” he said. “But kids are curious; they snoop. Education emphasizing the importance of gunlocks might have helped some children.”

Targeting education is also necessary, Keller said, since nearly one-third of all shooting injuries occurred in seven ZIP codes in the city of St. Louis and neighboring north St. Louis County.

In communities experiencing 20 or more shooting injuries during the five-year time period, the study found the average household income was $24,861. “People in these high-risk areas need more resources” such as violence-prevention programs, overall educational and job opportunities and activities for children, particularly after school, Keller said. “Without outside help, their risk for firearm injury increases.”

More than half of the shootings occurred between 6 p.m. and midnight, researchers found, reflecting similar findings in a recent study by the U.S. Department of Justice. “Instituting a mandatory juvenile curfew doesn’t hurt as an intervention,” Keller said, “but it should not be the main intervention.”

The study also noted that overall firearm deaths increased after Missouri repealed a permit-to-purchase law in 2007. That law required anyone purchasing a handgun to get a license confirming he or she had passed a background check. After its repeal, an additional 55 to 63 firearm-related homicides occurred annually in Missouri from 2008 to 2012, according to a study by researchers at Johns Hopkins University and published in the Journal of Urban Health.

Choi PM, Hong C, Bansal S, Lumba-Brown A, Fitzpatrick CM, Keller MS. Firearm injuries in the pediatric population: A tale of one city. Trauma Acute Care Surgery. January 2016.