Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have received a five-year, $6.5 million grant to study the physiological underpinnings of developmental disabilities in children and to use the findings to search for novel ways to improve such children’s lives.

The grant, from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), renews funding for the university’s Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (IDDRC).

The IDDRC, which opened in 2010, is one of 14 such centers in the United States. Work at the center focuses on clinical and translational research, with an emphasis on four key areas: prevention of premature birth and its consequences, identification of clusters of symptoms in infants that put them at risk for developmental problems, detailed characterizations of the developing human brain, and use of genomics to identify new treatment targets for specific disorders in individual children.

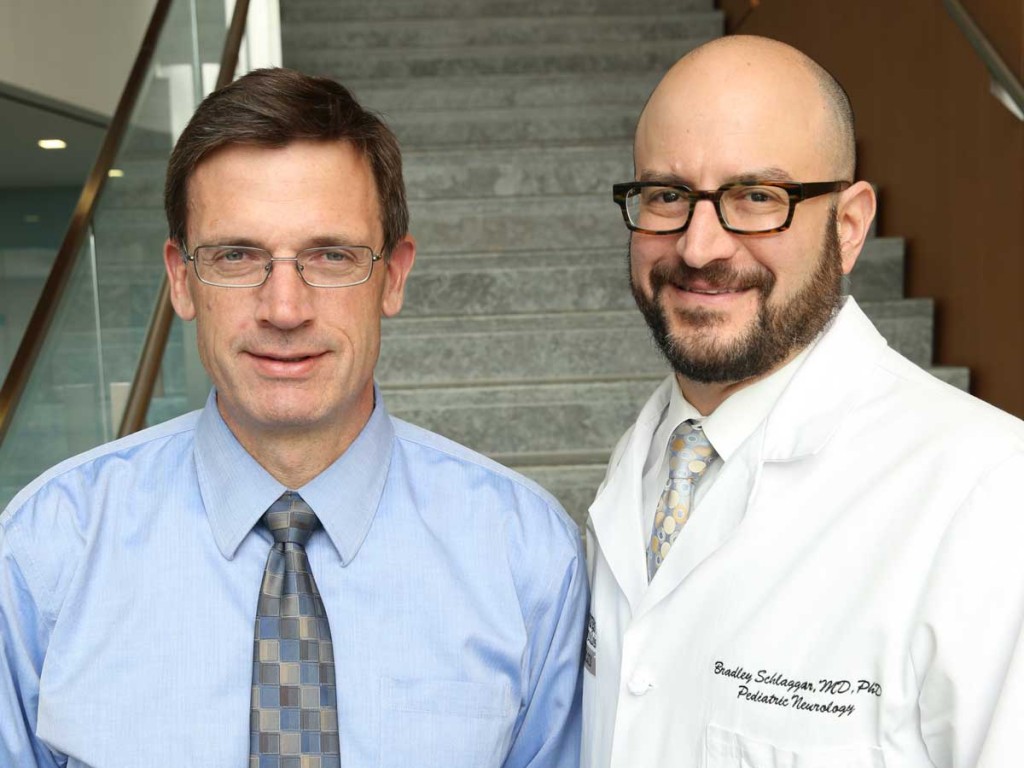

The center’s directors are John N. Constantino, MD, and Bradley L. Schlaggar, MD, PhD. Constantino is the Blanche F. Ittleson Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, director of the William Greenleaf Eliot Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and psychiatrist-in-chief at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. Schlaggar, the A. Ernest and Jane G. Stein Professor of Developmental Neurology, directs the Division of Pediatric and Developmental Neurology and serves as neurologist-in-chief at St. Louis Children’s.

In addition, Alan L. Schwartz, PhD, MD, the Harriet B. Spoehrer Professor of Pediatrics and head of the Department of Pediatrics, chairs a committee of associate directors at Washington University’s IDDRC. The group is made up of senior scientists in genetics, anatomy and neurobiology, psychology and other disciplines critical to discovery in developmental disabilities.

“One major goal is to take advantage of the revolution in genomic technologies that is allowing us to learn what underlies developmental disorders,” said Constantino. “What began here at Washington University with the Human Genome Project is allowing us to look at the complex genetic makeup of individual patients and to understand how variation in DNA drives development. By understanding different genetic paths of families affected by intellectual and developmental disability, and how those paths converge on mechanisms of brain and mind development, we hope to identify new targets for earlier and more effective treatment.”

The center also will take advantage of sophisticated new technologies to model and understand how brain cells function in individual patients.

“Easily obtainable tissues, such as baby teeth or kidney cells harvested from urine samples, can be reprogrammed into stem cells that subsequently become neurons, allowing us to understand more about how brain cells with an individual patient’s precise genotype are living and communicating — or not communicating — in specific infants,” explained Schlaggar. “That should help us better understand what can go wrong in the brains of children who have developmental disabilities, and what goes right in the brains of resilient children who develop normally in spite of risk factors such as genetic susceptibility or preterm birth.”

Schlaggar and Constantino said the IDDRC will work closely with similar centers around the country. The strategy is for all 14 centers to harness their individual strengths and share resources with scientists at the other centers so that it will be possible to more quickly convert new discoveries involving those strengths into high-impact interventions for individuals with developmental disabilities.