An illness is a story — a tale of burdens borne, lives altered, symptoms experienced, diagnoses given, cures attempted and health restored, or not.

This fall, the College of Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis has launched a new minor in medical humanities. Housed in the Center for the Humanities, the program is designed to explore issues of health, disease and medical care as core human experiences, and to examine those experiences with insights and critical methods drawn from humanities disciplines such as literature, philosophy, history and the arts.

We sat down with program founders Rebecca Messbarger, PhD, professor of Italian, of history, of art history and of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, all in Arts & Sciences; and Corinna Treitel, PhD, associate professor of history, to discuss the minor, the meaning of the medical humanities and the relationship between the arts and sciences.

First things first. What are the medical humanities?

Messbarger: The phrase “medical humanities” emerged decades ago in medical schools as a way of reconnecting students with the human side of medicine. The increasing rise of data-driven medicine was seen to produce doctors who were incredibly talented in biology, chemistry, pharmacology and physiology, but who struggled to interact with patients in mutually meaningful and satisfying ways.

So a lot of the medical humanities is about listening. How do you decipher what people are saying? Why do patients use certain types of words to describe their conditions? How do you deal with the discomfort of not knowing all the answers?

These questions are very familiar to people in the humanities. In a sense, literature is a laboratory in which we learn to listen to another voice. Medical humanities, especially in an undergraduate context, focus on the human experience of illness and care as given meaning in texts: literary, historical, religious, philosophical, visual, musical, etc.

Indeed, in near perfect opposition to the big data analytics of biomedical research — which aim to generalize and classify patient illness and treatment based on troves of information culled in the clinical context or harvested at the molecular or genetic level — the humanities address universal themes through discrete works for which specific times, spaces, cultures, human lives and individual perspectives are paramount.

Is there a danger of “instrumentalizing” the humanities — that is, of predicating their value simply on their ability to make better doctors?

Treitel: I have nothing against making better doctors! But it’s true that some faculty worry that this minor will only serve pre-meds.

What Rebecca and I are trying to do at WashU — and it really is an experiment — is to keep the focus on the humanities. We both feel pretty strongly that we want a mix of students with a genuine interest in the humanities as well as students going into the social sciences or medicine or other health care professions.

It’s a big umbrella. But students are hungry for courses that unite different sides of campus. They want to bring together the various parts of their intellectual lives.

Messbarger: The students are really ahead of us. Some people may worry that this puts the humanities in service to the sciences, but our students don’t see it that way. Listening, communication, critical thinking, the ability to analyze narrative — these are wonderful tools that also happen to be very important to medical practice. Language is crucial to anyone caring for people.

Treitel: It’s the old idea of the liberal arts: that there is value in preparing to think broadly, rather than just preparing for a career.

Talk about the minor. How are you rolling this out? What classes are you offering?

Treitel: Well, we’ve gone through a lot of discussion and revision. In the end, we decided on a two-year trial that’s only open by admission. Students have to apply, and we’ve capped it at 20-25 per class. So its pretty small, but this allows us to control the composition. We want students with different intellectual agendas.

Messbarger: There’s also the pragmatics of making sure we have enough course offerings for the number of students who wanted to take them. Hopefully, after the first two years, there will be a natural expansion of the program and of admissions.

Right now, we have some new classes and some extant classes — but there are two we have established as gateways. One is Corinna’s very popular course on “Health and Disease in World History.” The other is a new course that I conceived, and for which Corinna is one the prime collaborating faculty, called “The Art of Medicine.”

Tell us about those.

Treitel: “Health and Disease” surveys practices relating to health and illness from around the world, from antiquity to the present. We start with the Western medical tradition and the classical traditions of India and China — which are very different — then track how those traditions change and evolve as they confront each other and encounter various diseases. We also look at the emergence of modern scientific medicine in the West, how that travels to various parts of the world, and the complex history of conflict and exchange with other forms of medicine.

Messbarger: “The Art of Medicine” is supported by an interdisciplinary teaching grant from the Provost’s Office. We have five collaborating faculty representing four schools: Corinna from Arts & Sciences as well as Krikor Dikranian from medicine, Patricia Olynyk from Sam Fox, Dan Moran from biomedical engineering and Elisabeth Brander, librarian of rare books at the Becker Medical Library.

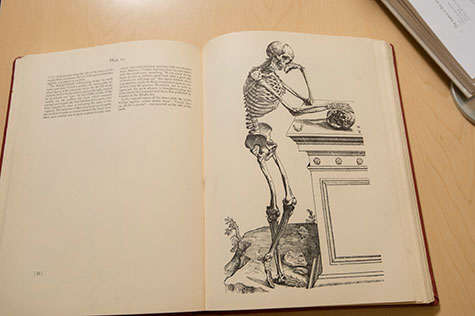

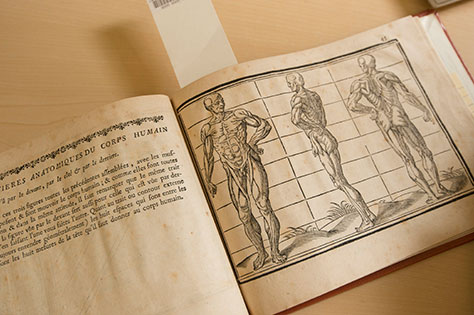

There’s some overlap with Corinna’s course, in the sense that we begin with Hippocrates and Galen and the origins of Western medicine. But as we move through the history, there’s a kind of dialogue between images of the body, literary text and medical text. By the time we get to Vesalius, the image — probably for the first time in history — really has more authority than the written word.

Printing technology was able to disseminate anatomical information to readers who didn’t have access to an anatomy table. It was a revolution.

It seems that, historically, distinctions between arts and sciences were less rigid than today …

Messbarger: Absolutely. Academic disciplines as we know them were invented in the 18th century. Think about someone like Galileo — a brilliant scientist who was also a vibrant, poetic writer. His treatises were written like dramatic comedies, with distinct characters debating contrasting viewpoints. One of the most popular poems of the 15th century was Hieronymus Fracastorius’s epic on “Syphilis,” which theorized the way contagion spreads.

Treitel: The pre-med track has become intensely specialized, but it used to be very common for pre-meds to major in English, history or philosophy. Last year, Rebecca and I ran a reading group that included a number of retired physicians. I don’t think a single one had majored in the natural sciences.

Conversely, you were a chemistry major.

Treitel: I was a chemistry major, so the division between the sciences and the humanities in the modern research university is something I’m passionate about. As an undergraduate, I was frustrated because my science professors didn’t have anything intelligible to say about the humanities, and my humanities professors had nothing to say about the sciences. In the laboratory, talking about human or social impact was almost taboo.

But the sciences and the humanities both offer important methodologies for understanding and improving the world. You can choose both.