While measles and the human papillomavirus (HPV) are vastly different diseases, failing to get vaccinated against them can have equally serious consequences, suggests Bradley Stoner, PhD, a medical anthropologist who studies infectious disease transmission at Washington University in St. Louis.

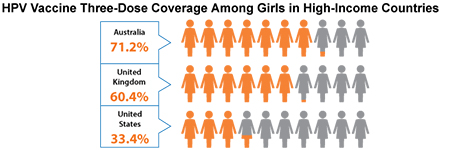

“HPV vaccine is highly safe and highly effective, yet vaccination rates in the US are embarrassingly low,” Stoner said. “Other countries have done a much better job of ensuring vaccination of the target population —adolescents and young adults.”

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes human papillomavirus as the most common sexually transmitted virus in the United States, suggesting that a large majority of sexually active people will acquire HPV at some point in their lives. It recommends the HPV vaccine for boys and girls at ages 12 and 13 so that they can develop an immune response to the virus before becoming sexually active.

While HPV infections may disappear on their own within a couple years, the CDC warns that having the virus increases the risk of developing deadly cervical, penile and anal cancers. Despite these concerns, only a third of those Americans who might benefit from the HPV vaccine are taking advantage of its medically proven protection, the CDC estimates.

Stoner, associate professor of sociocultural anthropology in Arts & Sciences and associate professor of infectious diseases in the School of Medicine, said part of the reason the United States hasn’t done well with the HPV vaccine is public financing.

In Australia, which has been offering free HPV vaccines to children and young adults since 2007, nearly 80 percent of the target population has received the vaccination, he notes.

“From a public health perspective,” Stoner said, “I think it’s also very important to explore the cultural beliefs and values within American groups and sub-populations that have served to limit the success of vaccination campaigns.”

Stoner, who teaches a popular course on medicine and society, said there likely are many reasons why some Americans resist public pressure to get themselves and their children vaccinated against diseases such as HPV.

He cites mistrust of the vaccine itself and concern that it may cause autism or other harmful conditions; a general mistrust of the medical profession and/or government recommendations about vaccination (the belief that kids are getting too many shots, for no good reason); religious objections to the vaccine among some religious groups, and the belief that getting the HPV vaccine will cause kids to become more sexually active.

“Instead of being so quick to castigate non-vaccinators, we as a society would be better served by exploring the belief systems that are driving this behavior,” Stoner said. “Learning more about the cultural barriers to vaccine acceptance can inform public health officials in their quest to develop culturally-sensitive approaches to encourage vaccine uptake.”