We all think we have a rough idea of what happened 12,000 years ago when people at several different spots around the globe brought plants under cultivation and domesticated animals for transport, food or fiber. But how much do we really know?

Recent research suggests less than we think. For example, why did people domesticate a mere dozen or so of the roughly 200,000 species of wild flowering plants? And why only about five of the 148 species of large wild mammalian herbivores or omnivores? And while we’re at it, why haven’t more species of either plants or animals been domesticated in modern times?

If nothing else, the tiny percentages of domesticates suggests there are limitations to human agency, and that it almost certainly is not true that people can step in and completely remodel through artificial selection an organism shaped for millennia by natural selection.

The small number of domesticates is just one of many questions raised in a special issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published online April 21.

The issue is the product of a 2011 meeting of scholars with an interest in domestication at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, a nonprofit science center jointly operated by Duke University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University.

Of the 25 scholars at the conference, two were from Washington University in St. Louis: Arts & Sciences’ Fiona Marshall, PhD, professor of archaeology, who studies animal domestication, and Kenneth Olsen, PhD, associate professor of biology, who studies plant domestication.

Both Marshall and Olsen are currently engaged in research on the crumbling margins of domestication where questions about this evolutionary process loom the largest.

Marshall studies two species that are famously ambivalently domesticated: donkeys and cats. Olsen studies rice and cassava and is currently interested in rice mimics, weeds that look enough like rice that they fly under the radar even when rice fields are handweeded.

Both Marshall and Olsen contributed articles to the special PNAS issue (see The story of animal domestication retold and Genetic study tackles mystery of slow plant domestications) and helped write the introductory essay that raises the big questions confronting the field.

“This workshop was especially fun,” said Olsen, “because it brought together people working on plants and animals and archeologists and geneticists. I hadn’t really thought much about animal domestication because I work primarily with plants, so it was exciting to see the same problem from a very different perspective.”

How much of it was our doing?

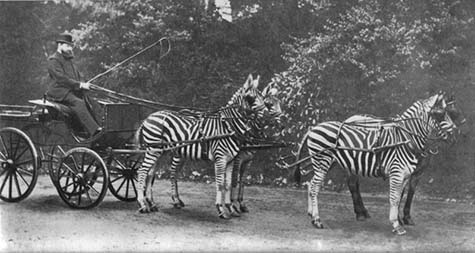

Many of our ideas about domestication are derived from modern experience with animal breeding. Anyone familiar with the huge variety of dog breeds, all of which belong to the same subspecies of the gray wolf, has some appreciation of the power of selective breeding to alter appearance and behavior.

But what about self-fertilizing or wind-pollinated plants, or for that matter, domesticated animals accidentally or deliberately bred with wild relatives?

Recent evidence that cereal crops, such as wheat or barley, evolved domestication traits much more slowly than had been thought has led to renewed interest in the idea that selection during domestication may have been partly accidental.

Charles Darwin himself drew a distinction between conscious selection, in which humans directly select for desirable traits, and unconscious selection, where traits evolve as a byproduct of natural selection in crop fields or from selection on other traits.

“The big focus right now is how much unintentional change people were causing environmentally that resulted in natural selection altering both plants and animals,” said Marshall.

“We used to think cats and dogs were real outliers in the animal domestication process because they were attracted to human settlements for food and in some sense domesticated themselves. But new research is showing that other domesticated animals may be more like cats and dogs than we thought.

“Once animals such as donkeys or cattle were caught,” Marshall said, “the changes humans sought to make were pretty minimal. Really it just came down to culling a few of the males and breeding all of the females.”

Even today, she points out, African pastoralists can afford to kill only four out of every 100 cows or they run the risk that drought and disease will wipe out the entire herd. “So I think outside of industrialized societies or special situations, artificial selection was very weak,” she said.

“In the donkeys and other transport animals, it’s not affiliative [tame] behavior the herders want,” Marshall said. “What they care about more than anything else is that their animals stay alive.”

So artificial selection is acting in the same direction as natural selection, or maybe pushing even harder, because humans often place animals in harsher conditions than natural ones.

“The comparable idea for plants,” said Olsen, “is the dump heap hypothesis, originally proposed by Edgar Anderson, a botany professor here at Washington University. The idea is that when people threw out the refuse of plant foods, including seeds, some grew and again set seed, and in this way people inadvertently selected species they were eating that also did well in the disturbed and nutrient-rich environment of the dump heap.”

“Cultivation practices play a huge role in selection,” said Olsen. “Traditionally in Southeast Asia, many different varieties of rice were grown simultaneously in a given field. It was a bet-hedging strategy,” he said, “that ensured some plants would survive and produce seed even in a bad season.” So it wasn’t people selecting the crop plants directly so much as people changing the landscape in ways that altered the selection pressure on plants.

How best to time travel

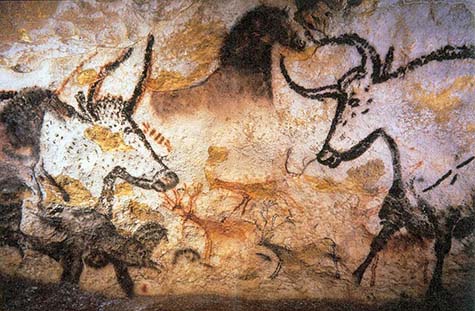

Questions about the original domestication events are difficult to answer because plants and animals were domesticated before humans invented writing, and so figuring out what happened has been a matter of making do with the limited evidence that has survived.

The problem is particularly difficult for animal domestication because what matters most is animal behavior, which leaves few traces. In the past, scientists tried measuring bones or examining teeth, looking for age or size differences or pathology that might plausibly be related to animals living with people.

“Sometimes there aren’t morphological shifts that are easy to find or they’re too late to tell us anything,” Marshall said. “We’ve gone away from morphological identifiers of domestication, and we’re going with behavior now, however we can get it. If we’ve got concentrations of dung, that means animals were being corralled,” she said.

Olsen, on the other hand, seeks to identify genes in modern crop species that are associated with domestication traits in the plant, such as an erect rather than a sprawling architecture. The techniques used to isolate these genes are difficult and time consuming and may not always penetrate as deeply into the past as scientists had once assumed because present-day plants are only a subset of the crop varieties that may have once existed.

So both Marshall and Olsen are excited by recent successes in sequencing ancient DNA. Ancient DNA, they say, will allow hypotheses about domestication to be tested over the entire evolutionary time period of domestication.

Another only recently appreciated clue to plant domestication is the presence of enriched soils, created through human activities. One example is the terra preta in the Amazon basin, which bears silent witness to the presence of a pre-Columbian agricultural society in what had been thought to be untouched forest.

By mapping distributions of enriched soils, scientists hope to better understand how ancient people altered landscapes and the effects that had on plant communities.

“It is really clear,” Marshall said, “that we need all the different approaches that we can possibly get in order to triangulate back. We’re using all kinds of ways, coarse-grained and fine, long-term and short, because the practical implications for us are quite great.”

After all, the first domestications may have been triggered by climate change at the end of the last ice age — in combination with social issues.

As a result, people abandoned the hunter-gatherer lifestyle they had successfully followed for 95 percent of human history and turned instead to the new strategies of farming and herding.

As we head into a new era of climate change, Marshall said it would be comforting to know that we understood what happened then and why.

“The Modern View of Domestication,” a special issue of PNAS edited by Greger Larson and Dolores R. Piperno, resulted from a meeting titled “Domestication as an Evolutionary Phenomenon: Expanding the Synthesis,” held April 7–11, 2011, that was funded and hosted by the National Evolutionary Synthesis Centre (National Science Foundation EF-0905606) in 2011.