Just as our bodies have skeletons, so do our cells. They’re equally indispensible in both cases. Without our bony skeletons we’d go limp and fall down. And without our cytoskeletons, our cells, which come in roughly 200 different shapes and sizes, would all become tiny spheres and stop working.

Using cells from the stem of a seedling as a model system, biologist Ram Dixit’s lab at Washington University in St. Louis seeks to understand the molecular mechanisms that organize and pattern the hundreds or thousands of microtubular “bones” of the plant cytoskeleton. In their model system, the microtubules form parallel bands like barrel hoops around the cell’s girth.

Dixit’s lab shows in the Oct. 24 online edition of Current Biology that misaligned microtubules that grow over existing microtubules are cut at the crossovers by the enzyme katanin, named for the katana, or samurai sword. Once a microtubule is cut, the part downstream of the cut falls apart, disintegrating into individual tubulin units.

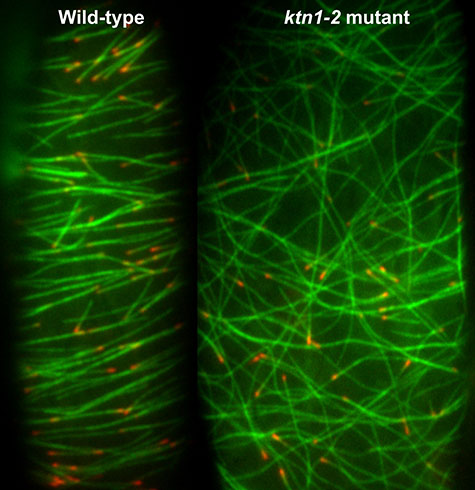

Because katanin shows up at crossovers just before a microtubule is cut and because there is no cutting in a mutant plant line lacking katanin, the WUSTL scientists are sure that katanin and katanin alone is responsible for this activity. In the mutant the microtubules form disorganized cobwebs.

The scientists also showed, by chilling cells to destroy their cytoskeletons, that katanin organizes the cytoskeleton in the first place as well as maintains its organization once it has formed.

Stars, hoops, fans and cobwebs

The cytoskeleton — whether it’s in an animal or a plant cell — is the framework that organizes the interior of the cell, said Dixit, PhD, an assistant professor of biology in Arts & Sciences. The cytoskeleton has two basic functions. It helps shape and support the cell, and it serves as a highway along which molecules and organelles move from one part of the cell to another.

To perform its functions, the cytoskeleton has to be organized in a specific pattern, however.

Animal cells have something called a centrosome, also called a microtubule organizing center, or MTOC. The surface of the MTOC is studded with microtubule nucleation complexes from which microtubules arise and to which they remain tethered. Given these constraints, its not hard to see why microtubules form starburst arrays around centrosomes.

But there are many cell types that have ordered microtubule arrays that aren’t created by centrosomes. Some nerve cells, for example, have very long projections (axons) that are chock full of microtubules.

The microtubules are aligned with the axis of the axon and they’re not connected to the cell’s centrosome in the cell body, which can be some distance away. “How do you order microtubules and generate a specific pattern when you don’t have centralized control?” asked Dixit.

The same question arises with muscle cells, which also have linear microtubule arrays and with the cells that line the gut, which have flat microtubule arrays in their flanks. In both cases, the arrays are distant from the cell’s microtubule organizing center.

The cytoskeletons in the cells of land plants are also patterned according to function without the help of a centrosome.

The guard cells that open and close the stomata on the under surface of plant leaves, for instance, have fan-shaped arrays that follow their curves. Pavement cells on the leaf surface that are shaped like interlocking puzzle pieces have net-like arrays. And rapidly elongating cells in plant stems have transverse arrays that then reorient toward the longitudinal direction as growth slows.

Lit up like a Christmas tree

It’s hard to study these arrays in animal cells, Dixit said. “The microtubules go deep into the cytosol and are hard to manipulate or image at high resolution. Besides animal cells, all have a centrosome, so that’s always a confounding factor.

“So we use plant cells as a model system instead,” Dixit said. They don’t have centrosomes; instead the microtubules nucleate at dispersed sites in the cell cortex, a layer of cytoplasm on the inner side of the plasma membrane. And when the cells are not dividing, the microtubules are plastered to the inside of the plasma membrane, where they’re easily accessible and easy to image.

The cells Dixit’s lab uses are from a lineage of Arabidopsis plants created by Erica Fishel, PhD, then a WUSTL graduate student in biology, that express two fluorescent tags, or marker proteins. One colors the entire microtubule fluorescent green and the other marks its growing tip cherry red.

Quan Zhang, PhD, who was a postdoctoral research associate in the Dixit lab, crossed this marker line with an Arabidopsis mutant that does not produce the katanin enzyme.

While a WUSTL undergraduate, Tyler Bertroche (AB ’11) generated a plant lineage where katanin is tagged with green fluorescent protein. Thanks to their efforts, the Dixit lab now has several different lineages of color-coded wild-type and katanin-mutant Arabidopsis.

Time is of the essence

“So how do cells pattern a microtubule array and how do different cells do it differently?” Dixit asked.

Microtubules originate in the cell cortex but once a cytoskeleton is established, they also sprout from existing microtubules in what is called branching nucleation.

Dixit and other scientists had shown through simulation that these branches would disorder the array unless some kind of pruning or culling mechanism was also in play.

Meanwhile, scientists at the University of Manchester in England had observed that misaligned microtubules were severed at junctions where a growing microtubule crosses an existing microtubule.

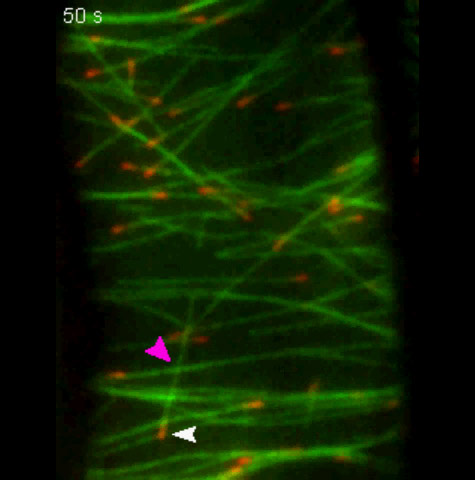

Zhang in the Dixit lab began with these observations and devised experiments to clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying them. He showed that they are insensitive to the geometry of the crossover or the stoutness of the underlying microtubule bundle. Instead, all that mattered was time.

How rapidly crossovers were cut determined what sort of array formed. In the transverse arrays, microtubules were cut, on average, within 41 seconds of a crossover event. In net-like arrays, on the other hand, cutting was three times slower and not as tightly controlled.

Plants have several severing proteins that might cut microtubules, but of these, katanin was the likeliest suspect. And in the katanin mutant, none of the crossovers were severed, demonstrating that this enzyme is solely responsible for cytoskeleton patterning.

To make sure, the scientists tagged katanin green and the microtubules red. When the cell was color coded in this way, they were able to see that katanin almost always localized to crossover sites before they were severed.

Coming in from the cold

These experiments showed that katanin was responsible for maintaining array patterning, but does it also create the pattern in the first place? To find out, Zhang used a trick he found in the literature, Dixit said.

Microtubules are cold-sensitive and fall apart when they are chilled. “So Quan would put cells in the freezer for four or five minutes, take a slide out, run to the microscope, and watch to see what happened as the cells warmed up,” Dixit said.

In the wild-type cells, the microtubules quickly reappeared and became well-ordered. In the katanin mutant, however, the microtubules re- appeared but never became organized.

The punchline, Dixit said, is that microtubules get cut at crossovers; the timing of the severing differs from one pattern to the next; katanin does the cutting; and if katanin is not present, the cells can neither generate or maintain ordered arrays.

This research was funded by a grant from I-CARES, the International Center for Advanced Renewable Energy and Sustainability at Washington University in St. Louis.