Archaeologists tunneling beneath the main temple of the ancient Maya city of El Perú-Waka’ in northern Guatemala have discovered an intricately carved stone monument with hieroglyphic text detailing the exploits of a little-known sixth-century princess whose progeny prevailed in a bloody, back-and-forth struggle between two of the civilization’s most powerful royal dynasties, Guatemalan cultural officials announced July 16.

“Great rulers took pleasure in describing adversity as a prelude to ultimate success,” said research director David Freidel, PhD, a professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “Here the Snake queen, Lady Ikoom, prevailed in the end.”

Freidel, who is studying in Paris this summer, said the stone monument, known officially as El Perú Stela 44, offers a wealth of new information about a “dark period” in Maya history, including the names of two previously unknown Maya rulers and the political realities that shaped their legacies.

“The narrative of Stela 44 is full of twists and turns of the kind that are usually found in time of war but rarely detected in Precolumbian archaeology,” Freidel said.

Carved stone monuments, such as Stela 44, have been unearthed in dozens of other important Maya ruins and each has made a critical contribution to the understanding of Maya culture.

Freidel says that his epigrapher, Stanley Guenter, who deciphered the text, believes that Stela 44 was originally dedicated about 1,450 years ago, in the calendar period ending in A.D. 564, by the Wak dynasty King Wa’oom Uch’ab Tzi’kin, a title that translates roughly as “He Who Stands Up the Offering of the Eagle.”

After standing exposed to the elements for more than 100 years, Stela 44 was moved by order of a later king and buried as an offering inside new construction that took place at the main El Perú-Waka’ temple about A.D. 700, probably as part of funeral rituals for a great queen entombed in the building at this time, the research team suggests.

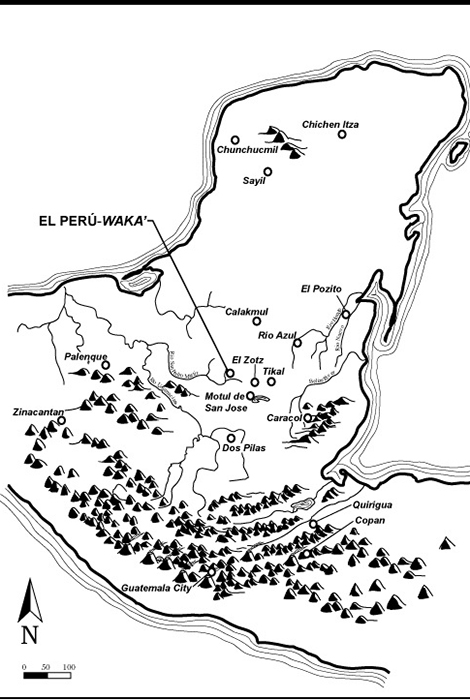

El Perú-Waka’ is about 40 miles west of the famous Maya site of Tikal near the San Pedro Martir River in Laguna del Tigre National Park. In the Classic period, this royal city commanded major trade routes running north to south and east to west.

Freidel has directed research at this site in collaboration with Guatemalan and foreign archaeologists since 2003. At present, Lic. Juan Carlos Pérez Calderon is co-director of the project and Olivia Navarro Farr, an assistant professor at the College of Wooster in Ohio, is co-principal investigator and long-term supervisor of work in the temple, known as Structure M13-1. Gautemalan archaeologist Griselda Perez discovered Stela 44 in this temple.

The project carries out research under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture and Sports of Guatemala and its Directorate for Cultural and Natural Patrimony, the Council for Protected Areas, and it is sponsored by the Foundation for the Cultural and Natural Patrimony (PACUNAM) and the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Early in March, Pérez was excavating a short tunnel along the centerline of the stairway of the temple in order to give access to other tunnels leading to a royal tomb discovered in 2012 when her excavators encountered Stela 44.

Once the texts along the side of the monument were cleared, archaeologist Francisco Castaneda took detailed photographs and sent these to Guenter for decipherment.

Guenter’s glyph analysis suggests that Stela 44 was commissioned by Wak dynasty King Wa’oom Uch’ab Tzi’kin to honor his father, King Chak Took Ich’aak (Red Spark Claw), who had died in A.D. 556. Stela 44’s description of this royal father-son duo marks the first time their names have been known to modern history.

A new queen, Lady Ikoom, also is featured in the text and she was important to the king who recovered this worn stela and used it again.

Lady Ikoom was a predecessor to one of the greatest queens of Classic Maya civilization, the seventh-century Maya Holy Snake Lord known as Lady K’abel who ruled El Perú-Waka’ for more than 20 years with her husband, King K’inich Bahlam II. She was the military governor of the Wak kingdom for her family, the imperial house of the Snake King, and she carried the title “Kaloomte,” translated as “Supreme Warrior,” higher in authority than her husband, the king.

Around A.D. 700, Stela 44 was brought to the main city temple by command of King K’inich Bahlam II to be buried as an offering, probably as part of the funeral rituals for his wife, queen Kaloomte’ K’abel.

Last year, the project discovered fragments of another stela built into the final terrace walls of the city temple, Stela 43, dedicated by this king in A.D. 702. Lady Ikoom is given pride of place on the front of that monument celebrating an event in 574. She was likely an ancestor of the king.

Freidel and colleagues discovered Lady K’abel’s tomb at the temple in 2012. Located near K’abel’s tomb, Stela 44 was set in a cut through the plaster floor of the plaza in front of the old temple and then buried underneath the treads of the stairway of the new temple.

Stela 44 originally was raised in a period when no stelae were erected at Tikal, a period of more than a century called The Hiatus from A.D. 557 until 692. This was a turbulent era in Maya history during which there were many wars and conquests. Tikal’s hiatus started when it was defeated in battle by King Yajawte’ K’inich of Caracol in Belize, probably under the auspices of the Snake King Sky Witness. The kingdom of Waka’ also experienced a hiatus that was likely associated with changing political fortunes but one of briefer duration from A.D. 554 to 657. That period is now shortened by the discovery of Stela 44.

The front of the stela is much eroded, no doubt from more than a century of exposure, but it features a king standing face forward cradling a sacred bundle in his arms. There are two other stelae at the site with this pose, Stela 23 dated to 524 and Stela 22 dated to 554, and they were probably raised by King Chak Took Ich’aak. The name Chak Took Ich’aak is that of two powerful kings of Tikal and it is likely that this king of Waka’ was named after them and that his dynasty was a Tikal vassal at the time he came to the throne, the research team suggests.

The text describes the accession of the son of Chak Took Ich’aak, Wa’oom Uch’ab Tzi’kin, in A.D. 556 as witnessed by a royal woman Lady Ikoom, who was probably his mother. She carries the titles Sak Wayis, White Spirit, and K’uhul Chatan Winik, Holy Chatan Person. These titles are strongly associated with the powerful Snake or Kan kings who commanded territories to the north of El Perú-Waka’, which makes it very likely that Lady Ikoom was a Snake princess, Guenter argues.

“Then in a dramatic shift in the tides of war that same Tikal King, Wak Chan K’awiil, was defeated and sacrificed by the Snake king in A.D. 562. Finally, two years after that major reversal, the new king and his mother raised Stela 44, giving the whole story as outlined above.”

Stela 44’s tales of political intrigue and bloodshed are just a few of the many dramatic stories of Classic Maya history that have been recovered through the decipherment of Maya glyphs, a science that has made great strides in the last 30 years, Freidel said.

Freidel and his project staff will continue to study Stela 44 for more clues about the nuances of Maya history. While the text on Stela 44 is only partially preserved, it clearly reveals an important moment in the history of Waka’, he concludes.

Editor’s Note: Science writers seeking a more detailed technical explanation of the findings and related research may click here for a downloadable technical summary of the project that was jointly written by the research team.