A lava tube once filled with red-hot magma flowing down a volcano dwarfs the cavers exploring it. The keyhole profile of this lava tube, on the volcanic island of Santa Cruz, suggests the floor of an upper tube may have collapsed into a lower tube from an earlier eruption. The “rope” hanging down into the tube is actually a tree root. The islands have no fresh water, and the plants in the jungle canopy seek water everywhere — or just enough humidity to make it through the dry season. (Credit: Aaron Addison)

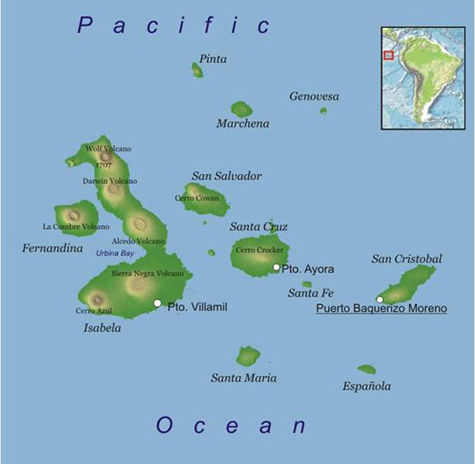

Whatever you did for spring break, Washington University in St. Louis’ Aaron Addison and Bob Osburn have you beat. They spent spring break mapping lava tubes — giant tubes through which red-hot rock once flowed — within a volcano on the island of Santa Cruz in the Galàpagos.

Despite the fame of the Galàpagos, many of its lava tubes, home to dark-adapted species unknown to science, never have been explored.

This year, during spring break, Addison, Osburn and a team of nine cavers were racing to map as many tubes as possible on Santa Cruz, which will be the venue for the 16th International Volcanospeleology Conference to be held March 15-22, 2014.

Totally tubular

Addison and Osburn saw their first Galàpagos lava tube during an Earth and Planetary Sciences field trip to the islands in the spring of 2006. Addison, director of Geographical Information Systems and Data Services, and Osburn, a laboratory administrator for the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Arts & Sciences — both of whom are speleologists — made a little side trip to a lava tube called Cueva de Gallardo, just to see what a lava tube looked like.

One look and they knew they would have to come back to the islands.

But getting permits to work in the Galàpagos, 97 percent of which is a conservation park, is notoriously difficult. Fortunately, they made a well-connected friend on the same trip: Theofilos Toulkeridis, a faculty member at the Escuela Politécnica del Ejército who does geological research in the Galàpagos.

With Toukeridis’ help, they were able to arrange trips in 2009, 2011 and this year.

Toulkeridis will host the international conference and co-chair it with Addison.

Into the magma chamber

The Galàpagos is a hotspot volcanic chain formed by a mantle plume, or upwelling of abnormally hot rock, in the Pacific Ocean near the equator. As a tectonic plate drifts over the hot spot, magma ascending from below melts, segregates from the rock and erupts to form a volcano.

A chain of volcanoes is formed as the crustal plate creeps over the hot spot. In a typical hot-spot volcanic chain, such as the Hawaiian Islands, the islands at one end of the chain are older and dormant and those at the other end are younger and still active.

The theory doesn’t quite work for the Galàpagos, however. The Galàpagos hot spot lies close to the Galàpagos spreading center, a mid-ocean ridge where the ocean crust is pulling apart, generating huge volumes of lava that probably are contaminating the hot-spot lava. The chemistry of the lavas suggests at least four reservoirs of magma are feeding the hot spot.

“Most volcanoes do not produce lava tubes,” Osburn said. “To get a tube the lava has to be fluid (basaltic rather than rhyolitic) and fairly hot. The eruption has to be fairly voluminous so that the flow continues long enough to channelize and for the channel to roof over. Volcanoes that erupt fluid basaltic lavas tend to form shield volcanoes with flat profiles and gentle slopes, which also favor the formation of long-lasting lava tubes.”

“Lava tubes form because cooling lava is a fantastic insulator,” Addison said. “As the lava begins to race down the slopes of the volcano, its outside cools much faster than the core, but because the cooled lava is such a good thermal insulator, the core remains superheated and can flow long distances, in some cases tens of kilometers.”

Mapping the tubes

During this spring’s expedition, Addison kept a blog of the team’s adventures, called “Galàpagos Cave Exploration — 2013”

that is full of astonishing images of the tubes (and a gorgeous photo of a fever of manta rays swimming off the pier at Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz).

“Despite its romantic associations, the Galàpagos is a very hostile place to do research,” Addison said. “The equator runs through the northern part of the archipelago, so it’s very hot and the days are very long. In the highlands, it rains almost every day. It wears you down.”

They stayed in a hotel that cost $14 a night, with only a fan for cooling, and not even that during the three total-island blackouts when the diesel generators broke down.

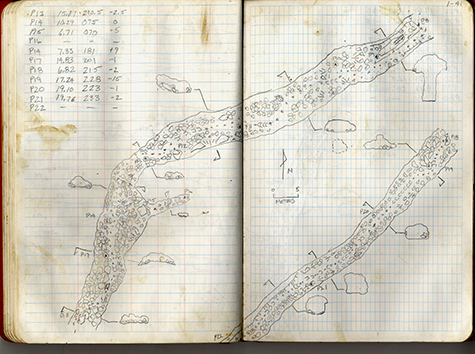

They located tubes by talking to local ranch owners, who often were able to lead them to openings to “tunnels” on their land. Once they found a tube, they took a GPS fix at its opening. Then, as they walked the tube, they charted the heading, elevation and distance between selected “stations,” and used those measurements to draw plan and profile maps of the tube.

They’ll be back to do it again for the international symposium — or sooner if they can organize the funds.

In the meantime, we all may be able to participate as well, if only vicariously. In 2012, Addison made the trip to the Galàpagos as a consultant for Colossus Productions, a production company shooting an IMAX movie of the Galàpagos starring David Attenborough. The film, called Galàpagos 3D, has been screened in the United Kingdom but has yet to be released in the United States. It features appearances both by Aaron Addison and his fellow WUSTL-affiliated Galàpagos enthusiast, Stephen Blake, PhD, who studies the migration habits of the giant tortoise.