Nominated early this year for recognition on the UNESCO World Heritage List, which includes such famous cultural sites as the Taj Mahal, Machu Picchu and Stonehenge, the earthen works at Poverty Point, La., have been described as one of the world’s greatest feats of construction by an archaic civilization of hunters and gatherers.

Now, new research in the current issue of the journal Geoarchaeology, offers compelling evidence that one of the massive earthen mounds at Poverty Point was constructed in less than 90 days, and perhaps as quickly as 30 days — an incredible accomplishment for what was thought to be a loosely organized society consisting of small, widely scattered bands of foragers.

“What’s extraordinary about these findings is that it provides some of the first evidence that early American hunter-gatherers were not as simple as we’ve tended to imagine,” says study co-author T.R. Kidder, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Our findings go against what has long been considered the academic consensus on hunter-gatherer societies — that they lack the political organization necessary to bring together so many people to complete a labor-intensive project in such a short period.”

Co-authored by Anthony Ortmann, PhD, assistant professor of geosciences at Murray State University in Kentucky, the study offers a detailed analysis of how the massive mound was constructed some 3,200 years ago along a Mississippi River bayou in northeastern Louisiana.

Based on more than a decade of excavations, core samplings and sophisticated sedimentary analysis, the study’s key assertion is that Mound A at Poverty Point had to have been built in a very short period because an exhaustive examination reveals no signs of rainfall or erosion during its construction.

Kidder (center) evaluate the Mound A excavations at Poverty Point. Katherine Adelsberger (seated left), then a Washington University graduate student (now professor at Knox College), and Rachel Bielitz, then a Washington University undergraduate, look on. (Credit: Courtesy photo)

“We’re talking about an area of northern Louisiana that now tends to receive a great deal of rainfall,” Kidder says. “Even in a very dry year, it would seem very unlikely that this location could go more than 90 days without experiencing some significant level of rainfall. Yet, the soil in these mounds shows no sign of erosion taking place during the construction period. There is no evidence from the region of an epic drought at this time, either.”

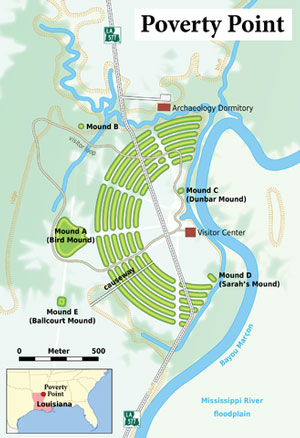

Part of a much larger complex of earthen works at Poverty Point, Mound A is believed to be the final and crowning addition to the sprawling 700-acre site, which includes five smaller mounds and a series of six concentric C-shaped embankments that rise in parallel formation surrounding a small flat plaza along the river. At the time of construction, Poverty Point was the largest earthworks in North America.

Built on the western edge of the complex, Mound A covers about 538,000 square feet [roughly 50,000 square meters] at its base and rises 72 feet above the river. Its construction required an estimated 238,500 cubic meters — about eight million bushel baskets — of soil to be brought in from various locations near the site. Kidder figures it would take a modern, 10-wheel dump truck about 31,217 loads to move that much dirt today.

“The Poverty Point mounds were built by people who had no access to domesticated draft animals, no wheelbarrows, no sophisticated tools for moving earth,” Kidder explains. “It’s likely that these mounds were built using a simple ‘bucket brigade’ system, with thousands of people passing soil along from one to another using some form of crude container, such as a woven basket, a hide sack or a wooden platter.”

To complete such a task within 90 days, the study estimates it would require the full attention of some 3,000 laborers. Assuming that each worker may have been accompanied by at least two other family members, say a wife and a child, the community gathered for the build must have included as many as 9,000 people, the study suggests.

“Given that a band of 25-30 people is considered quite large for most hunter-gatherer communities, it’s truly amazing that this ancient society could bring together a group of nearly 10,000 people, find some way to feed them and get this mound built in a matter of months,” Kidder says.

Soil testing indicates that the mound is located on top of land that was once low-lying swamp or marsh land — evidence of ancient tree roots and swamp life still exists in undisturbed soils at the base of the mound. Tests confirm that the site was first cleared for construction by burning and quickly covered with a layer of fine silt soil. A mix of other heavier soils then were brought in and dumped in small adjacent piles, gradually building the mound layer upon layer.

As Kidder notes, previous theories about the construction of most of the world’s ancient earthen mounds have suggested that they were laid down slowly over a period of hundreds of years involving small contributions of material from many different people spanning generations of a society. While this may be the case for other earthen structures at Poverty Point, the evidence from Mound A offers a sharp departure from this accretional theory.

University excavations of Mound A at Poverty Point. While doing work at

the site, researchers collaborate closely with the Louisiana Office of

State Parks to conduct educational and outreach efforts that enhance

understanding of the rich history and archaeology of America’s native

inhabitants. (Credit: Courtesy Photo)

Kidder’s home base in St. Louis is just across the Mississippi River from one of America’s best known ancient earthen structures, the Monk Mound at Cahokia, Ill. He notes that the Monk Mound was built many centuries later than the mounds at Poverty Point by a civilization that was much more reliant on agriculture, a far cry from the hunter-gatherer group that built Poverty Point. Even so, Mound A at Poverty Point is much larger than almost any other mound found in North America; only Monk’s Mound at Cahokia is larger.

“We’ve come to realize that the social fabric of these societies must have been much stronger and more complex that we might previously have given them credit. These results contradict the popular notion that pre-agricultural people were socially, politically, and economically simple and unable to organize themselves into large groups that could build elaborate architecture or engage in so-called complex social behavior,” Kidder says. “The prevailing model of hunter-gatherers living a life ‘nasty, brutish and short’ is contradicted and our work indicates these people were practicing a sophisticated ritual/religious life that involved building these monumental mounds.”

# # #

Editor’s Note: The U.S. Department of the Interior issues a news release Jan. 17, 2013, on its nomination of the Poverty Point site for inclusion in the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage List. The DOI news release is available here.

Learn more about World Heritage at whc.unesco.org