When cigarette taxes rise, hard-core smokers are more likely than lighter smokers to cut back, according to new research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

“Most clinicians and researchers thought these very heavy smokers would be the most resistant to price increases,” says first author Patricia A. Cavazos-Rehg, PhD. “Many believed this group was destined to continue smoking heavily forever, but our study points out that, in fact, change can occur. And that’s very good news.”

Cavazos-Rehg, a research assistant professor of psychiatry, and her team analyzed a subset of data from a large study documenting the prevalence of alcohol and drug use and associated psychiatric and medical conditions. The study identified 7,068 smokers and asked them how much they smoked. Three years later, researchers went back and asked the smokers the same question.

“On average, everyone was smoking a little less,” says Cavazos-Rehg. “But when we factored in price changes from tax increases, we found that the heaviest smokers responded to price increases by cutting back the most.”

The study was published in the journal Tobacco Control.

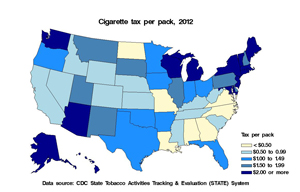

When the study began, the typical smoker averaged 16 cigarettes per day. After three years, that number had declined to an average of 14 cigarettes daily. During the period between the surveys, the price for a pack of cigarettes increased from an average of $3.96 in 2001 to $4.41 in 2004. Most of the increase was due to hikes in state taxes.

The researchers found that individuals who smoked 40 cigarettes (two packs) each day would have been expected to cut back by 11 the number of cigarettes smoked daily with no price hike.

But in states where cigarette taxes rose by at least 35 percent, heavy smokers lowered their daily smoking by 14 cigarettes, on average.

Among those who smoked less, rising prices had less of an impact. Individuals smoking 20 cigarettes (one pack) per day, would have been expected to cut back by two cigarettes without a price increase, but in response to a 35 percent increase in price, they only reduced their smoking by three cigarettes a day.

So in response to the higher taxes, heavy smokers cut back by an average of 35 percent. Lighter smokers smoked about 15 percent fewer cigarettes.

The researchers also looked at other potential explanations for why smokers cut back, but no other factors were as influential as price.

“Other research has shown, for example, that smoke-free indoor air policies can reduce the number of cigarettes that people smoke,” says Cavazos-Rehg. “But our study didn’t find that. There weren’t a lot of changes in indoor smoking policies during the time period in which these surveys were conducted. So we can’t say those policies don’t help reduce smoking. It’s just that we didn’t find they had a big impact in our results.”

In addition, other factors may be at play. For example, Cavazos-Rehg says heavy smokers are more likely to develop serious health problems that could provide an extra incentive to quit or to cut back. Plus, heavier smokers are more likely to get encouragement to quit from a doctor or family member.

Although the heavy smokers in this study cut back, she points out that health benefits are certain only if they stop altogether.

“They’re not quitting, but they are reducing their smoking behavior,” says Cavazos-Rehg. “We don’t know whether there’s any health benefit if they continue to smoke, even if they are smoking less. However, if reducing helps an individual to quit eventually, then the health advantage becomes clear.”

Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Chaloupka FJ, Luke DA, Waternam B, Grucza RA, Bierut LJ. Differential effects of cigarette price changes on adult smoking behaviors. Tobacco Control, vol. 21, published online Nov. 2012: doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050517

Funding for this research comes from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Support also comes from the American Cancer Society. NIH grant numbers are UL1 RR024992, KL2 RR024994, K02DA021237, K01DA025733, K02 DA021237 and R21 DA026612.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.