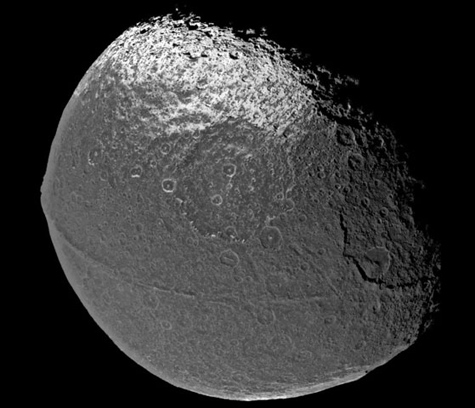

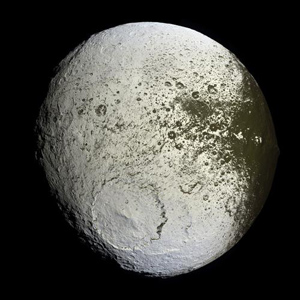

NASA/JPL/SSI

A ridge that follows the equator of Saturn’s moon Iapetus gives it the appearance of a giant walnut. The ridge, photographed in 2004 by the Cassini spacecraft, is 100 kilometers (62 miles) wide and at times 20 kilometers (12 miles) high. (The peak of Mount Everest, by comparison, is 5.5 miles above sea level.) Scientists are debating how the ridge might have formed.

For centuries, people wondered how the leopard got its spots. The consensus is pretty solid that evolution played a major role.

But the international planetary community only has had five years to ponder the unique walnut shape of Saturn’s bizarre moon Iapetus, considered by many to be one of the most astonishing features in the solar system.

And there’s no consensus as to how a mysterious large ridge that covers more than 75 percent of the moon’s equator was formed. It has been a tough nut to crack.

But now a team, including an outer solar system specialist from Washington University in St. Louis, has proposed a giant impact to explain the ridge, up to 20 kilometers tall and 100 kilometers wide.

William B. McKinnon, PhD, professor of earth and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences, and his former doctoral student, Andrew Dombard, PhD, associate professor of earth and environmental sciences at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC), propose that at one time Iapetus itself had a satellite, or moon, created by a giant impact with another big body.

The sub-satellite’s orbit, they say, would have decayed because of tidal interactions with Iapetus, and the sub-satellite would have gradually migrated toward Iapetus.

At some point, the researchers say, the tidal forces would have torn the sub-satellite apart, forming a ring of debris around the 735-kilometer-radius Iapetus that would eventually slam into the moon near its equator.

“Imagine all of these particles coming down horizontally across the equatorial surface at about 400 meters per second, the speed of a rifle bullet, one after the other, like frozen baseballs,” McKinnon says. “Particles would impact one by one, over and over again on the equatorial line. At first, the debris would have made holes to form a groove that eventually filled up.”

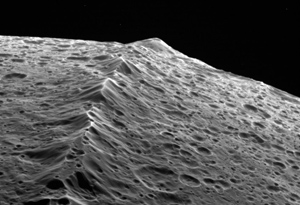

NASA/JPL/SSI

In 2007, Cassini flew within a few thousand kilometers of Iapetus’ surface to take this dramatic picture of the ridge. A movie of the flyby is available at the NASA site devoted to Saturn.

“When you have a debris ring around a body, the collisional interactions steal energy out of the orbit,” Dombard says. “And the lowest energy state that a body can be in is right over the rotational bulge of a planetary body — the equator. That’s why the rings of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are over the equator.

“We have a lot of corroborating calculations that demonstrate that this is a plausible idea,” Dombard says, “but we don’t yet have any rigorous simulations to show the process in action. Hopefully, that’s next.”

Other planetary scientists believe the ridge was created by endogenic (within the planet) activity such as volcanism or mountain-building forces.

“Some people have proposed that the ridge might have been caused by a string of volcanic eruptions, or maybe it’s a set of faults,” McKinnon says. “But to align it all perfectly like that — there is just no similar example in the solar system to point to such a thing.”

“There are three critical observations that any model for the formation of the ridge has to satisfy,” Dombard says. “They are: Why the feature is sitting on the equator; why only on the equator; and why only on Iapetus. I think we have something here that explains all those observations.”

Dombard will make a presentation on the preliminary findings Dec. 15 at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. The team also includes Andrew F. Cheng, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and Jonathan P. Kay, a graduate student at UIC.

Dombard says that Iapetus’ Hill sphere — the zone close to an astronomical body where the body’s gravity dominates satellites — is far bigger than that of any other major satellite in the outer solar system, accounting for why Iapetus is the only body known to have such a ridge.

“Only Iapetus could have had the orbital space for the sub-satellite to then evolve and come down toward its surface and break up and supply the ridge,” he says.

One of the supporting calculations the team performed was an estimation for how long it would take the orbit to decay so that the material would reach the point where the tidal forces would tear it apart into a debris disk.

“We’re looking at only 100,000 years for a sub-satellite relatively close (to Iapetus) to a billion years for a body that’s at the limit of where you could have a stable satellite in orbit around Iapetus,” Dombard says. “These time scales are certainly plausible considering we have several billion years of time to work with. And longevity is important, because if it happens too fast, all geological trace will be lost.”

McKinnon notes that there are other examples in the solar system of giant impacts creating moons that orbit planets, notably our own Moon and Pluto’s moon, Charon.

“Our Moon and Pluto’s, too, are actually retreating from the Earth and Pluto,” McKinnon says. “But if we were to bring our Moon inside what is called geosynchronous altitude, that special altitude where TV broadcast satellites (and other objects) are able to hover over one spot on Earth as they orbit, then the Moon would actually spiral in toward Earth.

“Eventually our Moon would break into a ring of particles as it got very close and was torn apart by tides, and then those particles would enter the atmosphere and bombard the Earth at the equator,” McKinnon says.